Cinema As Negation

“An artist,” Nagisa Oshima once observed, “does not build his work on one single theme, any more than a man lives his life according to only one idea.” In this cautionary note to critics, Oshima speaks equally to the multifarious style of his own works, to their restless wealth of themes and concerns, from the conflicts of youth, to criminality, oppositional politics, violence, and sexuality. His earliest films produced at Shochiku — A Town of Love and Hope, Cruel Story of Youth, and The Sun’s Burial — explore a sombre landscape of wayward youth and social outcasts scrabbling at the dregs of the postwar economic boom. Neither romanticized nor stylized, Oshima’s protagonists are fundamentally powerless, living on the edges of a saturnine, authoritarian social order. His gaze fixes precisely on the complex psychology of their weakness.

On October 12, 1960, Shochiku withdrew Night and Fog in Japan, after a mere four days in theaters. Oshima decried the “massacre” of his film as nothing less than political repression, but it was just as clearly a self-imposed break with the studio, one that led him to renounce the New Wave moniker and embark on independent production. His critique of the uniformity of “the Japanese film” is as much a rejection of the aesthetic values and craft of the studio system, for rather than refining and polishing his film style like a traditional artisan, Oshima forever begins anew, taking each project as the occasion to reinvent his cinematic language through experimentation and self-negation. In place of studio-produced program pictures, he sought to open a space for “individual films”, recasting the director-supervisor [kantoku] as an autonomous artist-creator [sakka].

The themes of crime and criminality recur in Oshima’s films, often as reminders of human dignity. In Japanese Summer: Double Suicide, the deserter Otoko becomes obsessed with the idea that somebody will “do him the favor” of killing him, while the countercultural drifters of Diary of a Shinjuku Thief must steal in order to achieve sexual gratification. Ostensible “true crime” stories such as Boy and Death by Hanging (both based upon real incidents) quickly depart from any familiar logic of crime and punishment. The unscrupulous parents in Boy direct their young son to fake injury by passing cars, as a ruse to extort “conscience money” from motorists. Death by Hanging goes beyond mere objection to capital punishment, dialectically obliterating the concepts of guilt and national identity. How, Oshima asks, can the state have a monopoly on killing, or on our identity? When the execution of “R” fails and he revives with no memory, the prison officers reenact his crimes in a bid to recover his identity and, by extension, his guilt. Yet to retrieve his culpability through the medium of imagination, R’s crimes become increasingly imaginary. We descend into a hideous farce, with R concluding: “a nation cannot make me ‘R’.” Inexorably, the bureaucratic logic of sanctioned death comes to resemble imperial aggression against another nation. Found responsible for murder of another, R is to be executed by the state, but if responsible for murder of R, must not the state in turn be executed by another?

With the production of Pleasures of the Flesh, Oshima became more involved in films concerning sexuality and censorship. These may be aligned roughly with the first wave of pink films by Tetsuji Takechi and Koji Wakamatsu, but more overtly concerned with constraints on freedom of expression. Insofar as pornography is less about “showing something” than making an audience think they will be shown something, Oshima speculates that it may have been invented as a way to avoid thinking directly about sex. Its control and suppression by the state corresponds to the invention of new methods that challenge the limits of sexual expression. In this sense, Oshima’s approach to the genre is more meta-pornographic.

In his defense of Realm of the Senses, Oshima argues that since obscenity cannot be defined, it is a legal category for something that has no concrete existence. It is what cannot be expressed or shown. Accordingly, if society wishes to resolve the “problem” of obscenity, it should simply allow everything to be shown. Only then could obscenity be rendered meaningless. Yet, Oshima is equally critical of the images of a false sexual abundance created by the mass media, a pernicious logic of “my sex” that resembles the anti-political “my home-ism” [maihomushugi] of the immediate postwar. “Without sexual freedom,” the Shinjuku thief opines, “humans will never be free.” But this idea is interrogated in turn: does this freedom entail the end of intimacy? And what does it mean to place it on the market? Isn’t the repression of sexual freedom through censorship just as problematic as “sexual GNPism”?

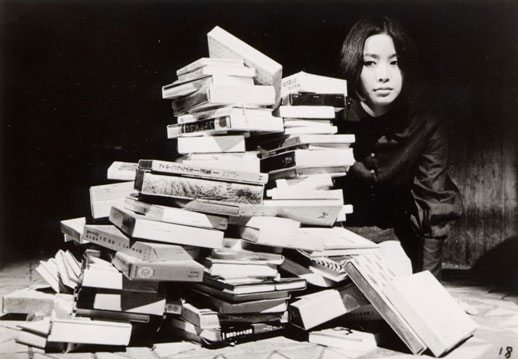

In 1969, Oshima looked back on Cruel Story of Youth and Night and Fog in Japan as tales of the anger and frustration of youth, the failed struggle against the U.S.-Japan Security treaty of 1960, and asked where adolescence begins and ends. Does it begin with innocence and hope, to end with heartbreak and frustration? For Oshima himself, it seems to have been the reverse: “my adolescence began with defeat”. Yet if he entered adolescence on that fateful afternoon in August 1945, he could equally say, twenty-four years later, “I think I am still in adolescence”. By the late 1960s, Oshima saw the end of adolescence neither in defeat nor frustration — having made peace with them long ago — but in the intellectual idleness of those who no longer read books, no longer discuss films, those who had surrendered their spiritual independence, ceased their rebellion, to passively absorb the “adult” discourse of the mass media. Cruel Story of Youth shows the perversion of youthful anger into defeat, but it also revealed a space of rebellious possibility, the image of a new adolescence for cinema.

From the exhausting long takes of Night and Fog in Japan, to the frenetic montage of Violence at Noon, Oshima’s film style is unusually demanding. Through his rough-hewn visual compositions and playful, theatrical distancing, ideas tend to trump plastic values and verisimilitude. The audience must extend all of its mental powers, and through this effort new relationships are formed. Evoking a distrust of “ambiguous Japan, where the instant anything is made it seems to be completely buried in reality,” Oshima sought a film style and practice that could negate reality. Thus, his infamous vows to banish the color green and shots of characters sitting on tatami. In this fashion, the camera becomes a device to convert landscape into fantasy, a means to deploy the fantastic as a weapon that negates the reality of postwar Japan. Oshima’s works stand as a testament to this effort, to a practice of endless self-negation. His films reflect a vision of cinema less as a monument to the artistic narration of what is known, than as an exploration of the unknown.

The Oshima retrospective is being held at the National Film Center until January 29.

M. Downing Roberts

M. Downing Roberts