Chinese Contemporary Art comes to Tokyo

Even if it is a meteoric trajectory, hence destined to fizzle out sooner or later, consider this: Artprice.com recently listed the Chinese oil painter Zhang Xiaogang as the second ‘most traded living artist’ in 2007 (in the realm of US$56.9 million), after Gerhard Richter. Moreover, the same source notes that 36 of the top 100 artists on that list were Chinese. The point is, that amount of ‘hot air’, even if only ephemeral, nevertheless represents a significant amount of energy in the global art scene that is difficult to dismiss.

Ultimately, of course, this remains merely a reflection of an elite, if expanding, art market. The fact is that such works represent the tiniest sliver of ‘Chinese contemporary art’, however one attempts to define what that is. Basically, it is a (slowly growing) handful of blue chip Chinese painters who consistently make the headlines, many of whom were amongst the first to be bought up by the earliest serious collectors of Chinese painting during the 1980s and 90s — incidentally, all of whom were foreigners. This has also meant that many recent ‘groundbreaking’ exhibitions of ‘contemporary Chinese art’ orbit around these early overseas collections, which may or may not have had any direct Chinese involvement in terms of curatorship, the loaning of works, and so on. This is not intrinsically bad, but should certainly be kept in mind.

In this respect, an exhibition of works from the Shanghai Museum of Art, ranging from 1979 to 2007, is actually an uncommon opportunity to see a dedicated Chinese collection of ‘Chinese contemporary art’ outside of China. As such, it could be understood as a small window onto a significant Chinese institutional collection of recent Chinese art, with many lessons for the astute viewer. But in acknowledging this aspect of the collection, one also has to bear in mind its attendant strengths and weaknesses.

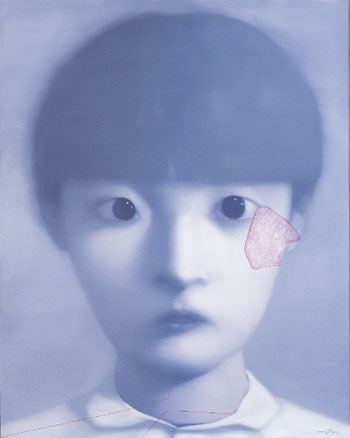

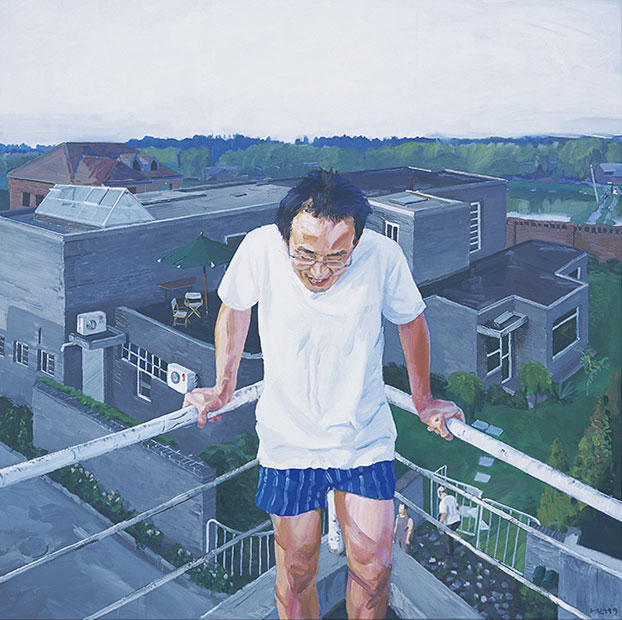

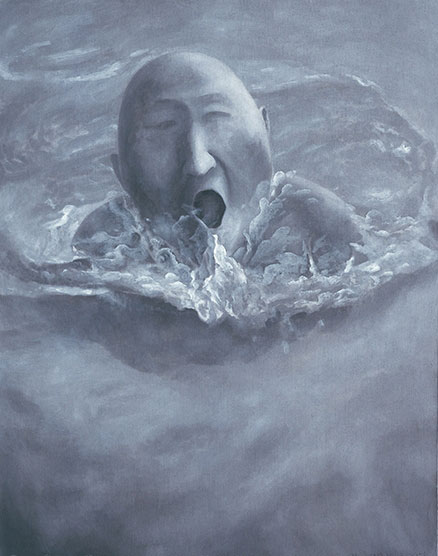

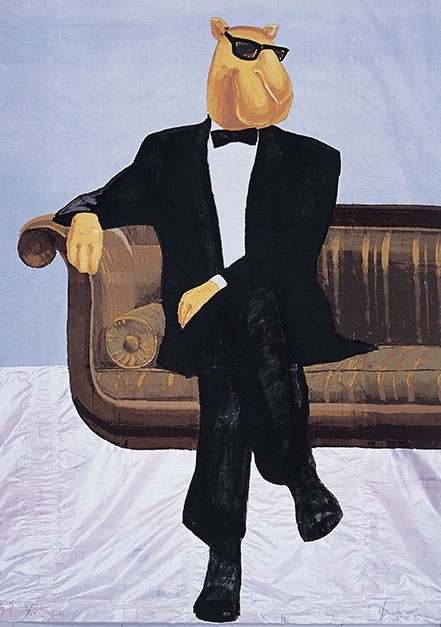

In terms of ‘weaknesses’, some may suspect that with all the ‘good’ works having been bought up early, the late-coming Chinese institutional collections (such as the Shanghai Art Museum) could only have managed to collect the leftovers, including conservative works that were of little interest to the headline-producing global market. It is possible to say that the handful of big name artists who feature in this show, such as Zhang Xiaogang, Liu Xiaodong, Fang Lijun or Zhou Tiehai, are not being represented by their ‘best’ works. Also, the bulk of work on show represents the huge variety of stylistic experimentation that emerged from the 1980s, and developed into the 1990s: it largely forays into once-taboo, formally modernist styles, even if sometimes to more sophisticated conceptual ends. While judgment of these claims remains up to viewers, these ‘weaknesses’ nevertheless are refreshing in their ability to dampen some of the hype that surrounds recent Chinese art.

This is not an exhibition of the latest and greatest. With one large room of paintings, and another for prints and works on paper, there are some significant works from the 1990s in particular, but there is little that is stylistically challenging. The value of the work lies in its context. For example, Pan Zhenguo’s remarkably abstract 1979 painting, a hilltop and some houses, suggested by triangularly pointed coloured shapes, swim in a sea of dripping fluorescent greens and pinks. Here, we see the artist still clinging to an outline of figurative suggestion, but only just.

The provenance of the collection — the Shanghai Art Museum, one of the most prominent collecting art institutions in China — places all these works into a context from which they are often disconnected when exhibited overseas, or when sold into the global market. Hence, pictures of personal urban angst or contemporary melancholy (Liu Xiaodong, or Zhao Xianxin) might sit alongside vaguely exotic or picturesque syntheses of light abstraction: China painted like Venice, as though channeling the ghosts of Matisse and Gauguin. The realism which underscores the education of all trained artists in China, to this day, thus manifests itself differently across a range of pictures; a difference in outcome which if nothing else underscores the claims for individual expression in some works more than others.

Such a mixture will not inspire those looking for ‘the’ cutting edge, as though the ‘new’ can be judged according to universal principles. Instead, with a nuanced viewing, this encyclopedic mix of paintings and prints offers a rare perspective on the local context of recent Chinese art, with some distance (for better or worse) from market forces, as well as the self-conscious ‘internationalism’ of most biennales.

—

1 The painting was Breeding Ground No.1 by Liu Xiaodong, from his ‘Three Gorges’ series, completed between 2005-2006. Xinhua News reported it sold at the China Guardian Spring Auction April 29, 2008, for 57.12 million yuan.

Olivier Krischer

Olivier Krischer