Bringing Monet to Tokyo: An Interview

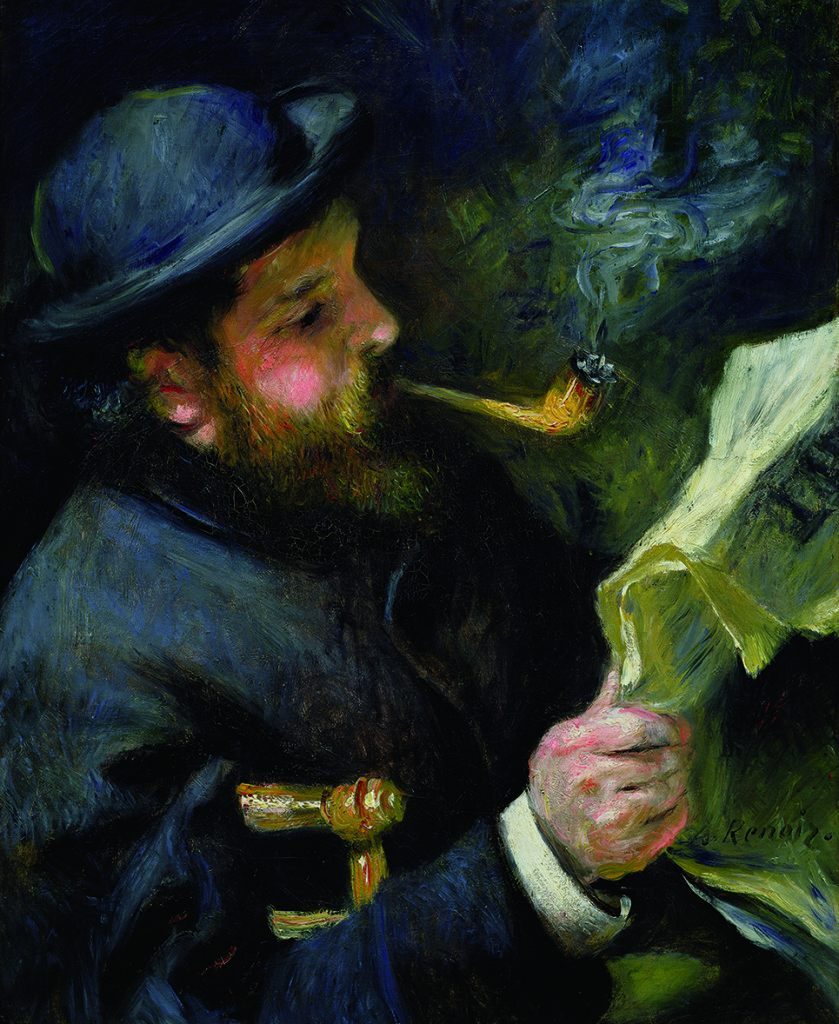

A large part of the Musée Marmottan Monet collection has been transported across the globe from its home in Paris to the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum for “Impressionist Masterpieces from the Marmottan Monet Museum.” A highly complex event to organize, the exhibition places Claude Monet’s paintings alongside art from his private collection, including works by Eugène Delacroix, Camille Pissarro and Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

This email interview details the logistics, relationships and negotiations that took place in order to put on the exhibition; consideration is also given to Monet’s painting. The responses are from the Nippon Television Network Corporation, one of the exhibition organizers, except for the final two questions, which are answered by Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum curator Natsuko Ohashi.

Why was it pertinent to arrange a Claude Monet exhibition, now, in Tokyo in 2015?

In 2014 Marmottan Monet Museum celebrated the 80th anniversary of its public opening. They had a special exhibition of the masterpiece “Impression, Sunrise” in Paris, and they’d been hoping to continue this commemoration. Thus, they’d decided to hold a large-scale exhibition in Japan, where Claude Monet is extremely popular.

The Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum regularly displays collections from museums across the globe. What is the nature of the museum’s relationship with the Musée Marmottan Monet?

Musée Marmottan Monet and Nippon Television Network Corporation have a long history, and two NTV presidents were members of Académie des Beaux-Arts. It is actually our third time to organize an exhibition of works from the Marmottan collection, which would not allow other Japanese media outlets to organize this kind of exhibition.

The exhibition is extremely popular, which means it can become quite crowded. What efforts are made in its organization to address this issue and ensure all visitors have a valuable experience?

We are very happy to see the turnout, with almost 350,000 visitors as of early November. We update regularly about the queuing time on our website and Twitter, and have been controlling the queue to offer a valuable experience. We may ask our guests to wait for a certain period for this reason, and advise you to come later in the afternoon.

How were the artworks transported to the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum?

By air from Paris to Tokyo, and by specially equipped trucks from the airport to the venue. (Please understand, due to security, we cannot provide details about transportation.)

Organizing this exhibition was presumably a very complex logistical affair, considering the list of companies and sponsors taking part is long. Could you provide an idea of how you went about putting this show together? How did you reconcile the different interests of so many people? What were the timeframes involved?

Since Claude Monet is one of the most famous and popular painters among Japanese people, Japanese organizers and sponsors are all happy and satisfied to have this exhibition. However, there was one controversial issue between the Japanese organizers and Musée Marmottan Monet, about the masterpiece ‘Impression, Sunrise’. We all wanted this painting to be at the venue for the entire period, but since this is such an important work for Marmottan, they insisted that they could lend it only for a limited period. Finally, instead of ‘Impression, Sunrise’ they agreed to lend another masterpiece, ‘The Bridge of Europe, Saint-Lazare Station’. It took around four to five years to conclude the whole negotiation.

To what extent does the current exhibition resemble the typical display of Monet’s works at The Musée Marmottan Monet? Was it simply a case of transporting the paintings and using an established curation model, or did you take a unique approach?

Since this exhibition is supervised by the deputy director of the Marmottan Monet Museum, it is basically based on the display at the Marmottan. However, we took a unique approach for the lighting of ‘Impression, Sunrise’ and ‘The Bridge of Europe, Saint-Lazare Station’.

I was surprised not to see more of an emphasis on Japonisme and Ukiyo-e, with comparisons made between, for example, Utagawa Hiroshige and Monet. Was there a conscious decision to place a greater emphasis on Monet’s Western and domestic influences?

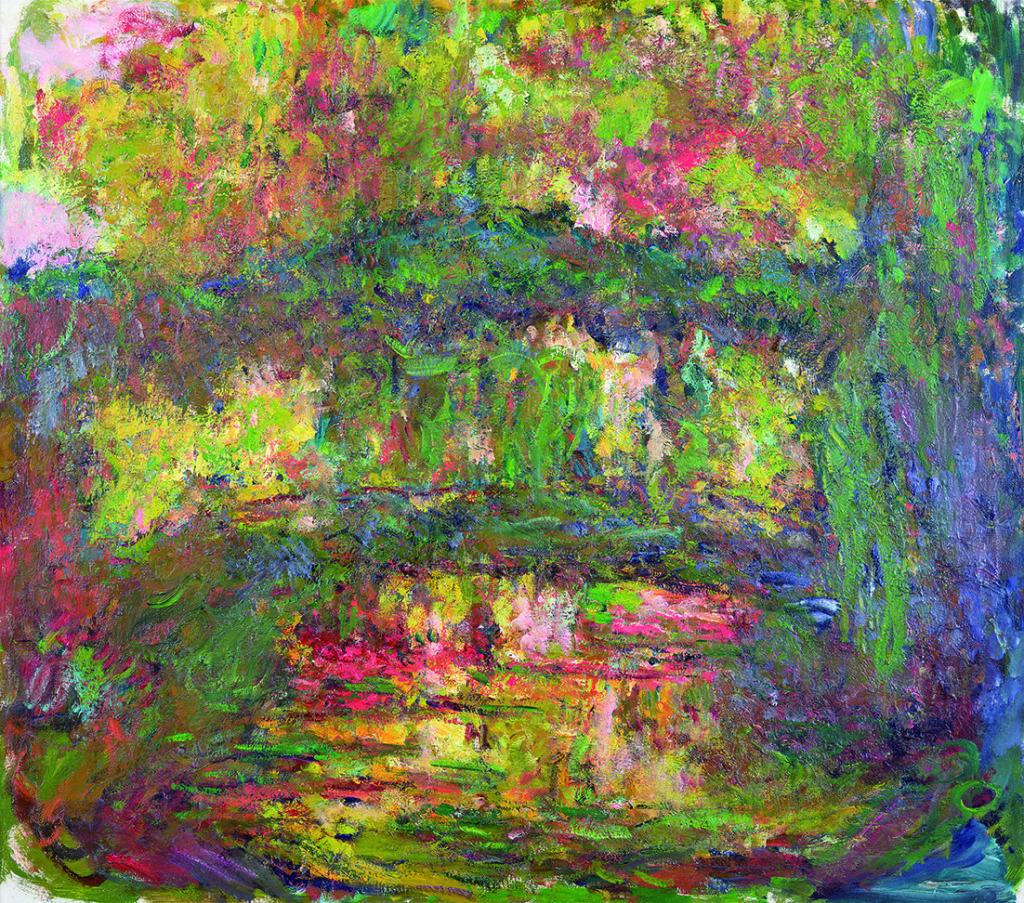

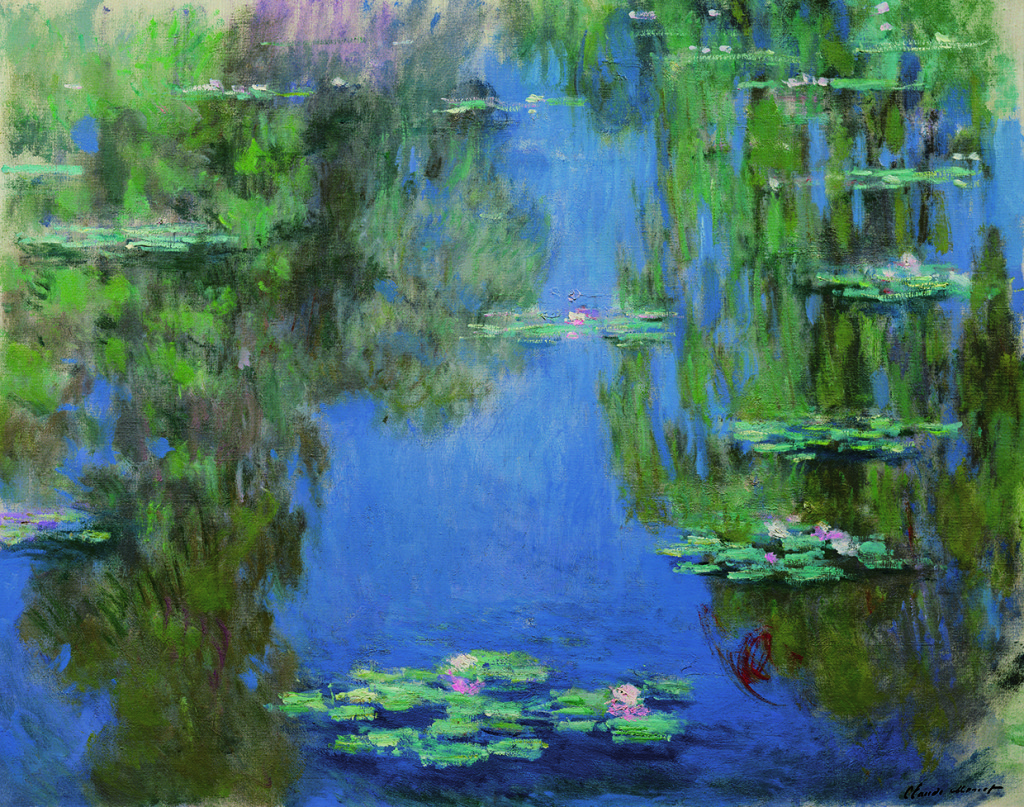

This exhibition is focused on Claude Monet’s private collection, which was kept by the painter until the last day of his life. It was then bequeathed to his son Michel, and then to the Marmottan. Thus, we’re focusing on Monet’s life as a painter, but not on Japonisme and Ukiyo-e influence. However, some pieces said to be influenced by Ukiyo-e are included in the exhibition, such as ‘The Row Boat’, ‘Water Lilies’, and ‘The Japanese Bridge’. We’ve mentioned those influences in display panels, and also in the catalogue.

It was interesting to see objects and artworks from Monet’s personal collection alongside his own paintings; there is real engagement with his life and sense of humor. What insights do viewers potentially gain through this?

We are displaying Monet’s private collection, which includes works by Delacroix, an artist Monet deeply admired, and Paul Signac, who was profoundly inspired by Monet. This collection allows us to learn how certain artists and works inspired Monet. It also shows Monet’s personal relationships and his interests in new trends.

Monet often repainted the same scene many times, repeating motifs through successive paintings. How important was the garden at Giverny to this working method?

As you mentioned, Monet repainted the same motifs many times, and the garden at Giverny was where he could observe and paint whenever he liked. Therefore, the garden was such an important place for him. Since this was a place he had control over, he could cultivate it in the same way he wished to paint. The garden was his masterpiece, and he continued to develop it through the last half of his life.

Calum Sutherland

Calum Sutherland