Botticelli and His Time

Looking at Botticelli’s The Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1475–1476), one would not guess it is the work of a young painter. It is ambitious but assured in its conception, hinting at the ruins of pagan Rome in the background as the birth of Christ heralds a new age, in what might be seen as a mirroring of the Medici family’s consolidation of power in Florence. The small crowd that has gathered displays a diverse array of postures, angles, and attitudes, from attentive or supplicatory to aloof or calculating. Vasari, writing in 1550, declared it to be Botticelli’s masterpiece. It may seem anti-climactic for the exhibition to place its most celebrated painting at the very beginning, but given its aim to address both Botticelli and the milieu in which he moved, it would be difficult to find a better introduction.

The painting doubles as a sort of “Who’s Who” of Florence in 1475 – there are three generations of the nigh-omnipotent Medici family, from Cosimo down to Lorenzo, in addition to poets, philosophers, and other social elites. To make more conspicuous the opulence in which this family lived, the exhibition displays an array of choice objects from their household (or rather, palacehold): a cup of onyx, a bowl of jade with gilded lettering, an illuminated volume of Aristotle.

Also shown are paintings and sculptures from some of Botticelli’s Florentine contemporaries, including the brothers Pollaiolo, Verrocchio, Fra Diamante, and Fra Filippo Lippi. (In addition to being Botticelli’s first teacher, Lippi is famed for belonging to the Friar Tuck tradition of clergymen with an insuppressible joie de vivre; his carousing proved such a hindrance to his work that Cosimo de Medici once locked him in a church to force him to complete a painting. This scheme failed, however, as Lippi was drawn by the sound of revelry outside the church and escaped through a window via knotted bed sheets, only to be found several days later.)

Of the ten or so of Fra Filippo Lippi’s exhibited works, only one indicates a definite influence on Botticelli: a charcoal sketch of a face later used in a Madonna; Lippi was one of the first to successfully imbue Mary with an air of tender maternity rather than regal solemnity, and the sketch possesses soft, dreamy features similar to those that Botticelli would paint again and again in his own Madonnas. Just as the type of feminine face Botticelli portrayed is thought to have been supplied by Simonetta Vespucci, honored as the most beautiful woman in Florence, Lippo’s wife Lucrezia Buti is believed to have been a model for his work, including the charcoal sketch mentioned above. Lippi met the beautiful but convent-bound Buti while painting for a church in Prato. Undeterred, he managed to convince her to sit as a Madonna for one of his paintings (no doubt belaboring the brush-strokes). He eventually seduced and brought her to a small, presumably picturesque town in the countryside (her father was said to have never smiled again), where she gave birth to a boy, Filippino Lippi, who would become Botticelli’s most renowned student. Filippino’s paintings are featured in the exhibition as well.

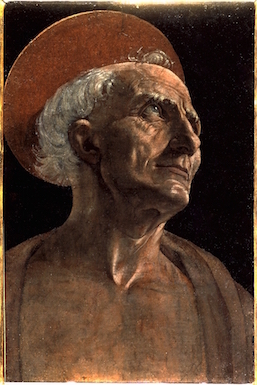

Seeing the works of his contemporaries only further underscores how markedly Botticelli differed from them. Take for example Verrocchio’s Study of a Head of Saint Jerome (ca. 1465). Even if one knows nothing of the 34 years Jerome supposedly spent translating the Bible into Vulgate and providing commentary for it, one can read in his face a life of intellectual toil, whose long solitude has diminished neither his resolution; all of this is made evident in the naturalism of the details: the careful modeling of the hollowed face, the spillikins of wrinkles around the eyes, the disheveled eyebrows, and the play of light and shadow across all of these.

Yet in the array of Botticellis in this exhibition we are met with portraits of an entirely different nature. La Bella Simonetta (ca. 1485-1490) and Portrait of a Young Man with Hand on His Chest (ca. 1482–1485) give no intimation of their subjects’ characters or the substance of their lives; they are unmarked by any experience. Walter Pater wrote that their expressions are those of people who shy away from the great decisions and tasks. These works are impersonal, their subjects detached from the world as from any possibility of action within it. In fact, throughout Botticelli’s work, real action of any kind is difficult to find. Depositions of the Body, Crucifixions, the exploits of saints or heroes, scenes requiring great emotional distress – Botticelli rarely paints these. (Curiously, the exception here is Judith, whom Botticelli paints a number of times. In the one featured in this exhibition, she is exiting the tent carrying the head of Holofernes in one hand and a sword in the other. But the sword seems weightless, the head is far too small, and she looks at it only with mild bemusement, as though it were a small stray dog that had wandered into her house and which she were promptly returning to the street outside.)

For Verrocchio, as for most painters in the early Renaissance, painting with more naturalism meant achieving a higher degree of truth; at times, these works seem more like a formal optico-geometric science than anything we would recognize with the term “art” today. Piero della Francesca, Brunelleschi, Masaccio, Uccello – all of them were fervent devotees of ratio and the mathematical distribution of space, and wrote treaties on the subject. For these artists, their development is bound up with the increased mastery of such principles. In Botticelli, the progression is not so clear. The latest painting by Botticelli featured in the exhibition, The Agony in the Garden (ca. 1495–1500), deliberately rejects them – the perspective is skewed to make background figures larger than those in the foreground, the figures are simple, there is no attempt to use light dramatically.

In this sense, The Adoration of the Magi seems to me to pose a sort of riddle within Botticelli’s development as a painter. When Vasari praises the painting, he does so in terms of the realism that held sway among the painters of the early Renaissance; he lauds the diversity of postures and attitudes, the spatial arrangement, the naturalism of the portraiture (He calls the rendering of Cosimo Medici “the best done to date”). As a work of realistic painting, The Adoration must rank among the best of the 15th century; it is certainly more skilled than any other Adoration of the same period. For any other painter, such a painting would be a revelation, a culminating expression of their powers, to be elaborated, or perhaps simply repeated, over the course of their career. Yet Botticelli seems to have rejected this path. When we think of the great paintings he would go on to produce afterward – The Allegory of Spring, The Birth of Venus, The May Magnificat, The Madonna of the Book – we do not think of their naturalistic or tonal qualities; rather, we recall their arabesque lines and contours given to figures in low relief, women so gracile he often had to make them look pregnant to give them any sense of weight at all, faces uniformly serene in their melancholy, somehow both pensive and vacant.

Looking at Botticelli’s works of this period, one feels that painting is not a vehicle for portraiture or drama, nor for what Leonardo Bruni called “the geometric perspective that includes and defines the historic function itself.” It seems all that is decorous and ornamental – be it tints of gold filigree, undulant lines, or the delicacy of sheer fabrics –possess order and place with a solemnity normally denied them. By extension, these works appear to make the case that beauty is no mere ornament, but something powerfully expressive of a reality that is greater and more important than that which we inhabit in our day-to-day lives.

Consider one of Botticelli’s most poetic paintings, Madonna and Child (Madonna del Libro) (ca. 1482–1483). Unlike his other madonnas, this one contains no retinue of angels, saints, or princes; there is only the Madonna and her child. She is not sitting on a throne beneath a Roman arch, but in a small study, with the child upon her lap. They have been reading the Book of Hours, perhaps in a sort of morning devotional, though the exercise has come to halt as they both turn to look at each other. It is the transcript of a brief moment between them, but in this one moment, Botticelli has compressed so much. Though Christ is only an infant, he has surmised something of his fate on earth and his is look is one of apprehension; the crown of thorns is already around his wrist, and the fruits of the Passion have ripened in the bowl by the window. His mother leans over him as though to shelter him from the world and its time passing outside the window. But what catches one’s eye are all the ornamental elements – the light blue cloth flowing down from the mother’s head to enwrap the infant Christ, the diaphanous veil catching the light between mother and son, the transparency of the sheet upon which the book rests, and that warm, electric gold – running through the tassels and stitching of a pillow, the fringes of her robe, the star embroidered on her shoulder, the haloes encircling their heads, the fretting of a chest – which in Botticelli always evokes an air of the eternal. The domestic and the universal, the delicacy of the present and the inevitability of fate, innocence and knowledge, time in its fleeting and eternal aspect – all of these opposites have converged in a single image. The poet Jaccottet noted that the Greek word cosmos has three meanings –first, order and propriety; then the world and universe; and finally, the finery of women. The source of poetry, he says, consists of those moments when the three perfectly coincide. Botticelli instinctively pursued something similar in his painting.

In the 1490s, the tone of Botticelli’s paintings changes once more, the cause generally thought to lie in his falling under the influence of the militant fire-and-brimstone prophet Savonarola, who would be executed in 1498 on charges of heresy. Botticelli abandoned his “heathen” paintings – there is an apocryphal story that he even burned a large number of them in a citywide Bonfire of the Vanities – and devoted himself to religious subjects, usually with more overt shows of suffering than in his previous paintings. The only secular painting he undertook in this period, which lasted for the remainder of his life, was The Calumny of Apelles (ca. 1494–1496), an intricate allegory based on a description by Lucian. One almost has the sense Botticelli knows he is indulging himself for the last time – he abandons himself to flowing of hair, fabrics, and bodies. The ten figures are positioned, or rather choreographed, in a more consciously dramatic way. But there is something stilted, mannered – the balance has been broken and is running toward excess. Unlike his previous paintings, this one is not inviting, in fact it seems purposefully remote and unfamiliar – the landscape reduced to two pale horizontal stripes, the extravagance of gold paneling and marble statues, and the austerity of the palatial design (one recalls what Wittgenstein’s sister said about the house her brother had spent years designing and exacting for her – “It seemed more like a dwelling for the gods than for a mortal like me”).

Our sentiments are sufficiently disengaged, and the light sufficiently cold, to feel more like a judge than a viewer. And if we are a judge, it seems we are to consider not the case of the calumnied victim, lost as he is in a private world of insanity, but the figure of King Midas; he has surrounded himself with scenes and statues of classical, heroic grandeur, yet he is so enfeebled that, though still young, he can hardly even lift his arm. The women around him, whose faces are all more or less identical, seem only to contribute to his anguish. Before him stands the figure of Envy, whom Botticelli has made the king’s double.

Botticelli may very well have identified himself with this pathetic figure – a man who has surrounded himself with riches exemplifying the Renaissance, but which end up leaving him cold; who knows that beyond those great arches lies an endless expanse of nothing; a man who therefore has sought in this gold and marble to be purified of the corporeal and the ephemeral, wishing, like Yeats in “Sailing to Byzantium” to “never take / My bodily form from any natural thing / But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make / Of hammered gold and gold enameling.” It appears he has grown disillusioned in his efforts, but has been eaten away by his inability to act. In this sense, Midas may be viewed as a development of one of those undecided and detached subjects that inhabit Botticelli’s earlier portraits. Perhaps Botticelli saw a resolution to these frustrations in Savonarola, who managed to combine a sort of apocalyptic mysticism with a militant resolve. In any case, Botticelli’s new style did not win him many admirers, and by the time he died in 1510 he was already something of an epigone. It would take nearly 400 years for his reputation to be restored – a legacy which this exhibition does an excellent job of preserving.

Parker Thomas

Parker Thomas