Beached and Marooned: The Aftermath of Leisure

Situating your gallery in a post-industrial warehouse district is like having a housewarming party for a belated excavation, second-hand and elegiac. It’s as if you’re commemorating the fact that someone got there first, the exciting first-phase nosing around and refurbishment long over. Sometimes the art hangs there forlornly in the white cube, like a corpse in a morgue at someone else’s funeral. The industrial ghost lingers, but it always seems as if that is what is meant to be celebrated, a faint structural afterglow rather than the present vitality that belongs to the art.

The gallery cluster in Kagurazaka has decided to avoid the nostalgia of ruin, locating itself in a living industrial area rather than a reformed post-industrial one. You walk down the winding slope and mossy stone staircase behind Akagi shrine, trying to dodge forklifts shifting fresh batches of newsprint and reams of unmarked paper. Together with Yamamoto Gendai, Kodama gallery shares the fourth floor of a battered building with a half-working cargo elevator, surrounded by the whirring of printing presses for ambient noise.

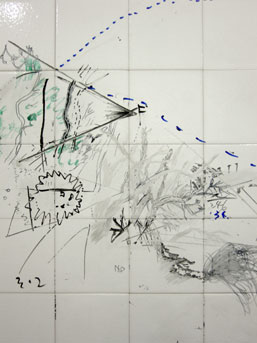

Inside, however, Kodama has kitted itself out in the standard white cube layout. This is actually an ideally bland setting, a neutral counterpoint to Masanori Handa’s spatially disorienting installation. Looking like a beached wreck after a typhoon, “sense-surfing” is an assemblage of scrappy materials marooned in a stark, clinical space. The entrance is half blocked by a collapsed lighthouse, built out of unpolished timber frame. The beacon attached to the end of the lighthouse is glass-paned and stuffed full of bits of wires and sockets that look like they were pilfered from model airplane kits. Hanging from the walls surrounding the lighthouse are several roughly daubed paintings on off-white tiles. One reads “cautioned against tidal waves” and depicts capsized boats, surfers buffeted and flung off their boards into violent waters, sparingly captured in a few terse brush strokes. Handa’s materials are junk-like and his technique deliberately slapdash. There’s an alarming urgency about the setup, harshly overlit and deafeningly silent, as you contemplate the “waves” that trashed the lighthouse.

There’s a desperate air of exhaustion in the workmanship, pregnant with deadened possibilities. With hardly any annotation from Handa, “sense-surfing” is sprawling and impressionistic rather than explicit. A valuable hint comes in the form of a scrawled caption at the bottom of one of the doodles: “kyouzame paradaisu to kankaku sa-fin to sono koutei”, which roughly translates as “languid paradise, sense surfing and its processes”. The drawings are processual, restless doodlings, records of ennui, of saturated and languishing senses. Like the afterparty at an all-night surfer rave on the beach, “sense-surfing” documents the fallout of excessive leisure, listlessly marking time after the storm with its lone, blinking semaphore: at precise six-second intervals, the collapsed beacon telegraphs its plight. Blink. Blink. Blink.

Darryl Jingwen Wee

Darryl Jingwen Wee