Barry McGee: Maintaining his Street Cred with Ease

This is especially the case when the artist is well respected and had become somewhat of a cult figure within both domains of the often opposing worlds of street art and commercial art. Barry McGee, who also goes by the moniker of ‘Twist’ within the graffiti and San Francisco street art community, is well known for having melded these two practices.

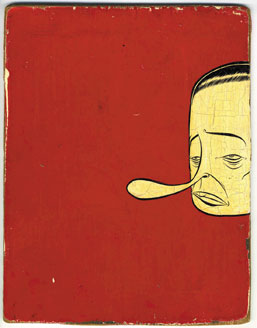

I have been an advent admirer of McGee’s work, mainly familiar with his trademark urban graphics, illustrations and paintings of sad cartoonish faces, empty liquor bottles and personal tags. These motifs have become recognisable and easily distinguished in a saturated market that is increasingly representing artists who began their careers anonymously decorating neighbourhood walls and tunnels before transferring and exhibiting their markings on the pristine white walls of galleries.

McGee has made what appears to be a seamless transition from the visual terrorism he inflicted on public locations, to making works that are as accessible and at ease in galleries and museums as they were when originally initiated and witnessed on the street.

The work continues to maintain an edge, which transcends the scepticism and cynicism that often follows creators from such backgrounds. Few come out when unscathed as they take the risk of transferring not only their work but also their habitual audience from the street into the setting of a gallery. Their style often ends up becoming hip and commercially viable, raking in the money but costing them their original credibility.

Throughout the exhibition McGee features his down-and-out men: their melancholic expressions tell of their struggles with alcoholism, unemployment, homelessness and issues of gentrification displacing already established residential communities from their neighbourhoods.

What is most surprising about the show is how he and the museum curators have transformed the space and utilised each floor of the museum, not only displaying his emblematic two-dimensional graphics but also his arresting large-scale installations, urban detritus and other ephemera.

Throughout the museum hyper real paintings and graphs are arranged in grid formations on walls, acting as technicolour backdrops. These motifs are repeated intermittently on television screens, and amidst a junkyard of cables, disused DVD and VCR players, painstakingly decorated with multicoloured hexagon graphics.

These differing sections of the gallery ultimately create an intriguing course that captivates, challenges and charms you as you wander through and move between the four floors of the venue. The most arresting sight – possibly intended as the show’s pivotal scene – is one that you can view from three differing vantage points throughout the museum: an overturned, graffitied Lorry on top of which five life-sized, hooded mannequins are balanced atop of each others shoulders, with the adolescent at the summit tagging the gallery wall.

It’s easy to think that the show ends here, but make sure that you don’t miss the additional delights around the main exhibition: a large mural in the basement café and the graffitied façade of a building across the road from the museum.

It is stimulating to see such site-specific works in reality rather than solely as two-dimensional reproductions. Reproductions don’t allow you to hear the whirring of the mechanical and motorized, spray-can wielding models that are placed within the space, making simulated acts of tagging. To also hear the clutter and commotion from the audio loops and blips in his video monitor installation and to feel as though you can smell the recently sprayed paint on his works, gives the audience an experience of artist’s process, his obvious commitment to his art practice and his experience of the city that is not just visual, but multi-sensory.

McGee still leaves his traces and scratchings on surfaces throughout the urban environments he passes through, though increasingly in recent years he has been commissioned to create site-specific installations for arts organizations and galleries such as this latest offering at Watari-um.

Though the space in which his work is viewed has shifted and is potentially more problematic his audience, his view remains constant and unaltered, and that is to capture, translate and transcribe the tensions and experiences of urban life.

Meighan Ellis

Meighan Ellis