Audio Architecture

21_21 Design Sight welcomed Yugo Nakamura to curate the exhibition Audio Architecture. Nakamura is acclaimed for his unique expressions in web interface design, film and installations. Given the freedom to present any genre, Nakamura took inspiration from an article by Sean Ono Lennon in the prominent Japanese fashion magazine Ginza, in which Lennon described the band Cornelius’s music as “audio architecture”. Keigo Oyamada (Cornelius) has produced a song exclusively for the exhibition. Additionally, nine up-and-coming creators from various artistic backgrounds manifest their own interpretations of “audio architecture” and their relationships with music in films and audio installations. Masamichi Katayama (Wonderwall) is in charge of the space design and has integrated all of the contrasting works into one spatial exhibition.

By initial impression, music and architecture may appear unrelated — one is appreciated through eyes and has physical weight, one is perceived through the ears and is intangible. From its title, one might imagine the exhibition to be about creating a new spatial experience through music and the sonic aspects of architecture. However, in reality, the “architecture” in this exhibition plays more of a metaphoric role, making us question our definition of music in daily life. It breaks down conventional notions of music as a linear sequence of notes and architecture as solely three-dimensional. It allows us to reexamine our understanding of the underlying structures of both subjects and further explore the potential of music.

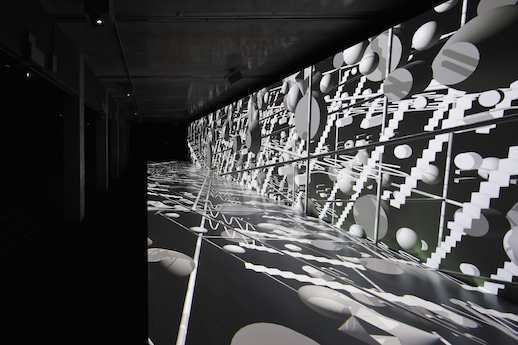

The philosopher Goethe describes architecture as “frozen music”, observing how the foundations of both correlate in rhythm, texture, harmony, proportion and dynamics. The entrance of the exhibition presents three screens that display Cornelius playing the song audio architecture. The visual switches every few seconds to different cuts and screens in a nostalgia-inducing construction that resembles a live studio performance. The following room presents a massive stage with the same music played on loop. Opposite the screen is the seating area, where audiences are able to sit and absorb what they see and hear, or go on stage and become a part of the music.

Masaya Ishikawa (Euphrates) and Shun Abe’s interpretations of music convey a message of “existing between simplicity and complexity”. Their visuals appear precisely constructed with detail and sophistication and later reveal how their patterns were created: with only two sheets of transparent film moving at a constant or specific speeds. While their works are distinct, rhythm and patterns exist in both scenarios, demonstrating that rhythm is found in music through beats and repetition as well as in shapes or patterns in the realm of architecture.

At the back of the main stage are eight booths breaking down the integrated film into sections for each individual artist. The audience can also experiment with the transparent sheets to create their own patterns. Koichiro Tsujikawa (Glassloft), Bascule, and Kitasenju Design have built an application to show music as interactive and playful, generating new relationships between music, film and audience members by letting people watch themselves listening to music. The visual effects follow audience movements and form new displays corresponding to each individual’s motions. яндекс

“Audio Architecture” expands our understanding of music and architecture. In the current world, these fields are no longer narrowly defined, and the show encourages us to reconsider the many ways music can be described and presented –– as static, speedy, thin, abstract, thick, heavy, light, wavy, solid, in shapes, or amorphous. It is not only a matter of perceiving through the eyes or ears, but also feeling the rhythm and immersing yourself in the space. The definition and experience of music continues to morph into more personalized, ever-evolving forms.