Assemblage of Tensions and Dissent

Behind Asakusa’s famous tourist spots hides half-century old residences, some in the Tawaramachi area. Tucked behind a colony of working-class residential structures is Asakusa – a 40-square-meter exhibition venue for contemporary art. The renovated building dating back to1965 made its debut as an art space in 2015 and most recently featured the works of Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhorn and Spanish artist Santiago Sierra in the exhibition “Radical Democracy.”

Both Hirschhorn and Sierra are known for a particular strain of social antagonism visible in their work in which the reality of conflict is highlighted over the ideal of Nicholas Bourriaud’s ‘relational aesthetics’. In this way they set themselves apart from other socially engaged artists who critic Grant Kester would describe as, “fulfilling religion’s traditional role in binding community.” Art historian Claire Bishop, on the other hand, might read Hirschhorn’s and Seirra’s works as a take on a messianic duty of promising a “better world to come” through their clear-cut emphasis on difference and tensions.

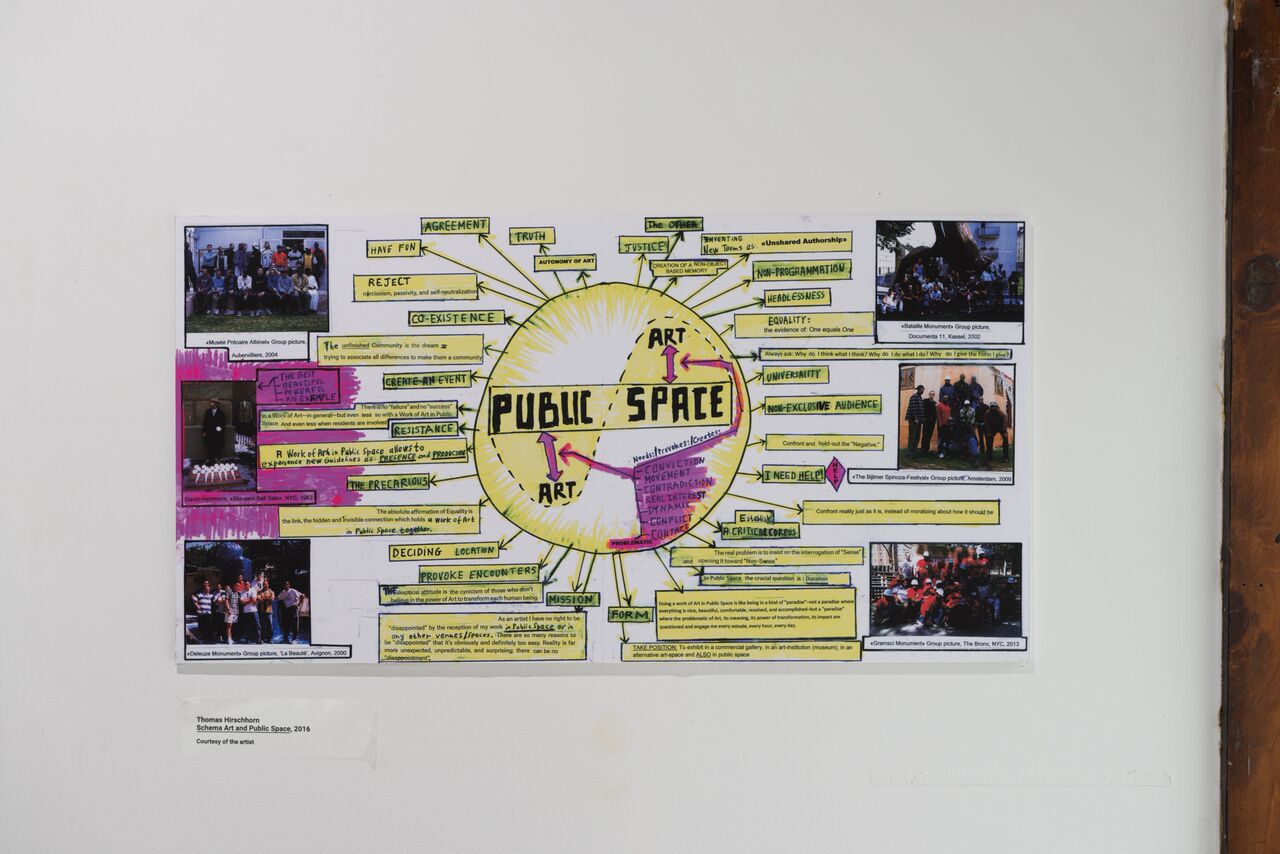

Hirschhorn has described his artistic process as one of “Presence and Production” where he defined it as a fieldwork confronting reality with the real. He uncovered and developed such an approach upon encountering difficulty working with people in his series of temporary monuments for his beloved thinkers, namely Spinoza, Bataille, Deleuze, and Gramsci. Just like Santiago Sierra, instead of hiding away tensions and contradictions in working with different people, they both utilized this as an advantageous and potent force to imagine an emerging community.

The monument series was presented as an archive in the form of an installation piece in Asakusa along with a video of Hirschhorn’s discussion with art historian Anna Dezeuze in which the two join in conversation the relation between art and precariousness and Hirschhorn’s motivation to bring a monument to thinkers revered by the art world to the everyday residential spaces of local people and involve these residents in the building and frequent reconstruction of such monuments.

Meanwhile, Sierra’s articulation of “structures of power that operate in our everyday existence” is presented in a single-channel silent video documenting his 2001 Venice Biennale performance 133 personas remuneradas para ser teñidas de rubio (133 persons paid to have their hair dyed blonde) in which immigrants to Italy from different parts of the world gathered upon the Arsenale to have their hair dyed en masse. Shot in black and white with a cinema verite-like documentation of people falling in line and waiting, its imagery disturbingly recalls that of the Auschwitz prison camp.

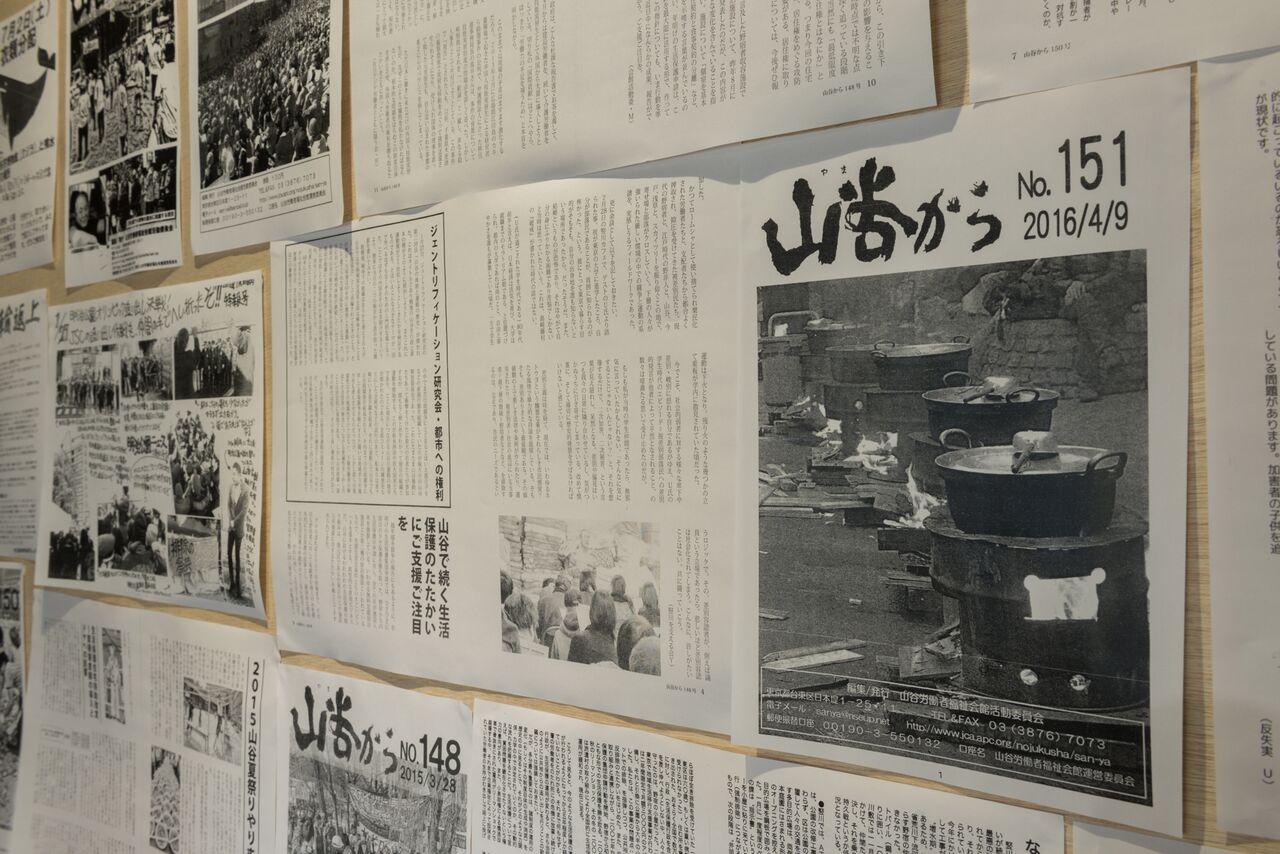

This exposure of situations of exploitation and marginalization along with dialectical democracy (creative dialectical tension between self and other – or Agonistic Democracy as espoused by Chantal Mouffe and Jacques Ranciere) and relations renders the expansive potential of art and its limitation. It is in this locus where the curatorial framing of the exhibition is grounded. Thus, it acted as a platform to question Japan’s homogenous society and also to “form a critical position to comment on Tokyo’s political landscape*”, further engendered by an accompanying assemblage of documents recording the local struggle of Asakusa’s Sanya day-laborers in the global context of dissent and a negotiation with rarefied labor as expressed in the works of Hirschhorn and Sierra.

As the fervor for “art projects” shows little signs of abating, and with an increasing currency being found in terms such as “socially-engaged art” this exhibition provides a bass tone from which critiques of such readiness to participate in full thrown consensus can begin to emanate, as a new beat of questioning of the artistic and ethical dilemmas of “social art” begins to make itself felt.

You can read Rei Kagami’s introduction to Asakusa here.

Jong Pairez

Jong Pairez