Asian Agitations—A Time of Unrest

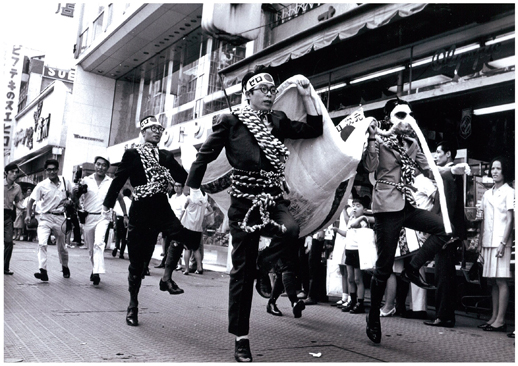

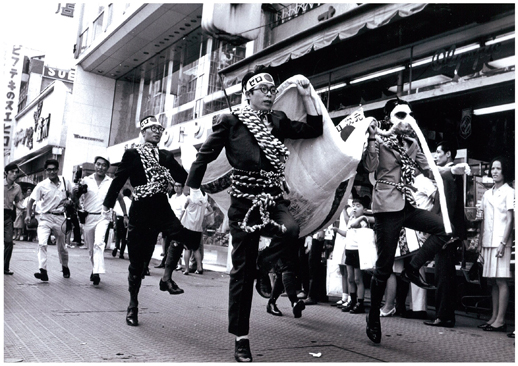

Photo: Kitade Yukio Courtesy: Kato Yoshihiro

Photo: Kitade Yukio Courtesy: Kato Yoshihiro

“We are art terrorists,” proclaims “Performance Rising in Rebellion Against Modern Civilization”, an essay penned by Yoshihiro Kato, leader of the radical performance group Zero Jigen (also known as Zero Dimension). In no too uncertain terms, these words reflect the volatilities of an age in which the authority of both the state and art history were placed under increasing scrutiny.

As the likes of Allen Kaprow, Josef Beuys and Wolf Vostell were making happenings and George Maciunas was leading Fluxus actions across America and Europe, as struggles for civil rights were reaching new heights, as anti-war sentiment came to emerge like never before, as students and the Left took dramatic measures and the cold war “us” vs. “them” sentiment was reaching boiling point…a lot was kicking off in East Asia, too.

“Great Crescent: Art and Agitation in the 1960s—Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan”is an archival exhibition, curated by Hong Kong’s Para-site, which initiates Mori Art Museum’s new research program dedicated to uncovering the complex layers and contexts of contemporary art in Asia. As its title indicates, this exhibition examines the early postwar era across three nations of troubled but undeniably deep ties. The force of modernism was in full swing: Japan was enjoying rapid economic growth (thanks in part to the Korean War), reaching new peaks of postwar redevelopment and taking new strides on the international stage, as the 1964 Olympics and 1970 Expo seemed to attest. South Korea was emerging from the shadow of decades of colonial rule and the bruised shock of the Korean war, experiencing continued unrest while simultaneously being flooded with funds from the US and Japan and enacting numerous development programs. Taiwan found itself in a political limbo and increasingly dependent upon US recognition and investment, but rapidly increasing its industrial output and foreign exports also aided it in diplomatic affairs.

Arranged in a timeline paralleling the social and political events of all three countries and in-laid with the pioneering actions of artists at this time, this exhibition allows visitors to trace the intersections between art and the shifting terrain of these key East Asian states. The timeline begins in 1960, with images of the overwhelming mass of people demonstrating against the Japan-US ANPO security treaty, which marked a new leg in the two countries’ relations. During this same time South Korea was witnessing student uprisings followed by a military coup, having suffered traumatic fraction in the Korean War. The years progress through Taiwan’s struggle for autonomy under official Beijing rule, a set of five-year development plans in South Korea under authoritarian rule, the progression of the Vietnam war, the 1965 Korea-Japan Treaty, student rebellions, the rise of the Red Army, the suppression of democracy movements, unsuccessful assignations and finally coming to a finale in the Osaka Expo and Yukio Mishima’s ritual self-disembowelment after his failed coup. All of these events are played to the drum beat of modernization, rapid industrialization and complete overhauls to the landscapes of the cities across these lands, set with the thick undertone of US presence.

Amongst these upheavals a number of artists including Chang Chao-Tang, Choi Boong-hyun, Chuang Ling, Hi Red Center, Huang Huacheng, Jeong Gang-ja, Kang Guk-jin, Yoko Ono, and Zero Dimension were expressing their own disquiet with the lie of the land. This exhibition introduces through photographs, film documentation and publications of the time, the legendary movements of these groups and individuals, revealing wit and playfulness at the same time as deep critique and resistance, asserting or questioning the political agency of the individual. Here these artists not only respond to the social upheavals of the era, a period in which the head of globalization was clearing rearing, and when the influence of the US seemed to be all-encompassing, but they also attack the structure of each instituted national art system, which appeared to have been only too happy to be coerced by Western modernism, with rigidly hierarchical and regulated notions of value which separated art from the grit of life. Here these artists lay claim to art as something to be physically collided with, breaking (quite literally) through the bounds of what was perceived as narrow convention and demanding that the act of creation be one of subversive disruption which was clearly embedded in the social and political flux of society.

Yoko Ono’s seminal “Cut Piece” is the most renowned work in this collection, and little more need be said as the individual’s capacity for violence when sanctioned on a collective basis, whether violence against women, or violence in war, is unveiled in brutal honesty by this iconic figure. Such familiar work creates the entry point for this archive, but what follows is a revelation of key groups and artists who may still remain under the radar in terms of global art history, but whose presence is essential in understanding the cultural climate of the time and the subsequent developments in contemporary art and performance in the region.

As the 1964 Tokyo Olympics drew near, Jiro Takamatsu, Genpei Akasegawa and Natsuyuki Nakanishi appeared on the streets of Ginza as Hi Red Center. Donning lab coats and wielding wash rags, soap and toothbrushes, they began to clean every inch of the side-walk with minute precision as “HRC Campaign to Promote Cleanup and Orderliness of the Metropolitan Area!” in a scathingly ironical gesture towards the capital’s transformation and violent upheaval in order to project the image to the international community of sophistication and economic advancement, in which cleanliness is next to the godliness of global success. This is an action which has inspired many artists and performance groups since and rings with particular resonance as Tokyo prepares for another costly overhaul for the 2020 games.

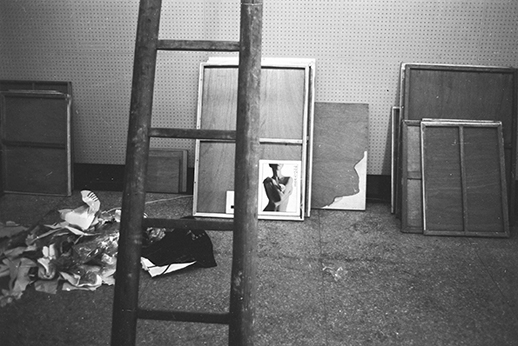

Photo and photo courtesy: Chuang Ling

Photo and photo courtesy: Chuang Ling

A year after Taiwan signed an agreement with Japan to receive financial investment towards economic and industrial development in a new level of modernization and as Taiwan struggled to find its identity caught between China and the US, in 1966 Huang Huacheng announced the “Manifesto of the Ecole de Great Taipei” with 81 clauses which rejected the art establishment and the claimed universalism of Western modernism, making satirical statements through such pearls of wisdom as:

9. Do not get over excited when conducting serious business…violators shall ejaculate prematurely.

57. One adjective is better than two. It is best not to use adjectives at all. Try to do away with metaphors and express the reality of the matter.

This satire was also expressed through an installation of readymade objects, including a doormat collage of western paintings, a washing line of dirty clothes which visitors were forced to pass under, a bed, a wash basin and poem collection, a record player of fashionable tunes, all coming together to create spaces inviting derision, rest, nihilism, poetry and populism.

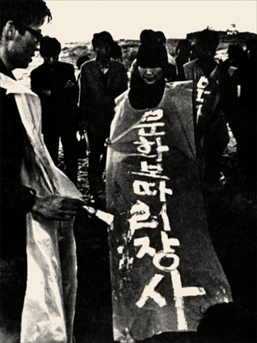

Courtesy: Korea Art Research Institute (KARI), Seoul

Courtesy: Korea Art Research Institute (KARI), Seoul

As the second five-year plan of development began in S. Korea in 1967, Choi Boong-hyun and associates performed the first happening in Seoul, entitled “Happening with a Plastic Umbrella and Candles”. This choreographed rotating action involved the encircling of an artist holding an umbrella and singing songs of a 19th century Peasant Revolution, the lighting of candles implanted into the umbrella’s canopy, which was then twirled as dripping hot wax flung in all directions before all the flames were urgently blown out. This happening questioned the drive of modern progress, the issue of energy and the establishment of the nuclear umbrella through the US-Japan Security Treaty, while also referencing other encompassing “umbrellas” of established art and cultural values and the will to break through these. Such sentiments were echoed in Jeong Gang-ja, Kang Guk-jin and Jeong Chan-Seung’s “Murders on the Han Riverside” (1968), which through the ritual burying of the three artists under the second Han River Bridge embodied the very consumption of the individual through development and the art establishment.

Courtesy: Korea Art Research Institute (KARI), Seoul

Courtesy: Korea Art Research Institute (KARI), Seoul

Ties between culture, state authority and the grip of capitalism were all too clear for many artists when it came to the 1970 Osaka Expo, seen by many as a firmament of US-Japan relations, coopting art and culture as a front for economic and military ties. Caught in the throes of psychedelia and resistance movements, peppered with Hare Krishna and now-illegal substances, Zero Jigen took to the streets of Nagoya, Tokyo and Osaka with sensationalist performances on a near monthly basis, consisting of writhing human chains of near-naked bodies, violently colliding characters, marching minions donning bowler hats, figures crawling the sidewalks wearing nothing but a gas mask, ecstatic gyrations of a collective held in bondage with the Hinomaru… Zero Jigen was an “anti-art” body fully immersed in the 60’s and 70’s counter culture, railing against globalism and “raping the city” as they saw it being raped by international conglomerates and political/economic opportunism. The video collage “White Rabbit of Inaba” 1970 is a witness to the extremes to which this collective was prepared to go to bring its message to the public, including several occasions of arrest for breaching the obscenity law.

Photo: Kitade Yukio Courtesy: Kato Yoshihiro

Photo: Kitade Yukio Courtesy: Kato Yoshihiro

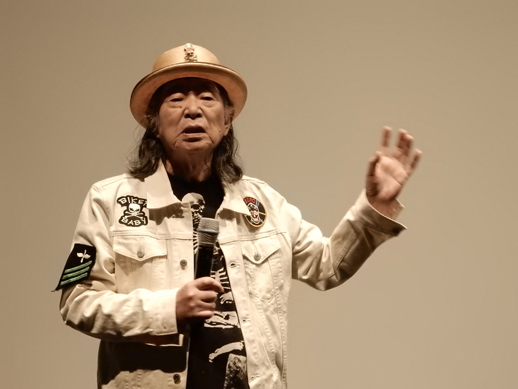

At a talk and screening on 30th June, 2015, as part of the exhibition program, Zero Jigen leader Yoshihiro Kato began with an outburst of both praise and disdain for Taro Okamoto, who simultaneously claimed an anti-Expo position while forming a center piece of the festivities with his Tower of the Sun, a monument to ancient Jomon culture piercing through the modernist constructions of Kenzo Tange. Inspired by this figure whose pre-dating work aggressively attacked the establishment, Zero Jigen was in no danger of being criticized as ambivalent in its own position. Kato stressed that “Art = Fight” and called upon artists to flex their “art libido” in creating something that is viscerally critical, a message sure to reach new ears as Zero Jigen enjoys a revival of interest with exhibitions planned in South Korea, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Thailand, as well as a new catalogue recently released by a French publisher. As Kato talks in the prestigious spaces of the Mori Art Museum, however, one might fairly say that Zero Jigen is now being courted a little too close by the art establishment as it tours the art museum spaces of East Asia. But this is the paradox even of this very exhibition.

As we delve into the past of political and artistic turbulence and examine the state of these three nations half a century ago, we may doubt how much things have really changed in 50 years. With US presence seemingly stronger than ever before, masses taking to the streets in anti-military demonstrations, students taking over parliament in Taipei, general strikes in Seoul, tensions between countries stirred by the media, all the while as the train of big business chugs on…the distinction may be hard to make and thus leads us to ask, in all of this, what “action” are artists taking now?

With this show’s valuable insight into the modern history of East Asia seen through independent and highly responsive art movements, we can look forward to future installments of this ongoing series of MAM Research. The exhibition ends on Sunday, 5th July.

Emma Ota

Emma Ota