Artists and the Disaster: Imagining in the 10th Year

With this year marking a decade since the Great East Japan Earthquake, Contemporary Art Gallery, Art Tower Mito in Ibaraki Prefecture presents Artists and the Disaster: Imagining in the 10th Year. The museum, which suffered earthquake damage and served temporarily as an evacuation center, displays the work of seven artists/art groups. Their work includes but goes beyond documentation, having expanded with time to encompass creative responses and imaginings of the future.

The first room presents a white curtain with a timeline of disaster-related events since the earthquake up through this year. Also exhibited are works by Haruka Komori + Natsumi Seo, a duo that has spent years in Iwate and Miyagi Prefectures documenting people’s lives and experiences. Seo’s texts recounting stories and her sketches portraying the changing landscapes are displayed in vitrines around the room, while videos by Komori showing reconstruction developments are mounted on the wall. The juxtaposition of national events and personal experiences is sobering yet compelling.

In “Double-Layered Town/Making a Song Through Trading Our Places,” Komori + Seo explore what it means to have your town rebuilt. The series combines video with written text and paintings capturing memories and visions of the future. Cited as an effort to “plant seeds for new folktales,” the project asks the participants to re-narrative stories about the town. In one video a speaker speculates, “In the new town they’ve made new families and live new lives.”

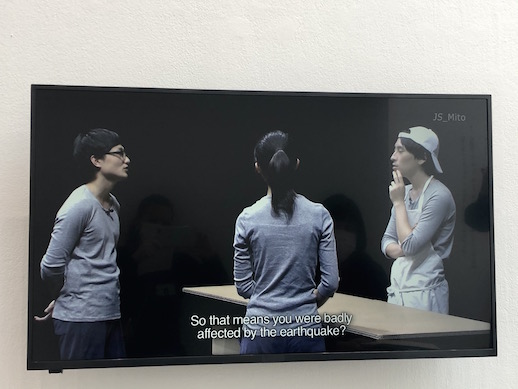

“Japan Syndrome” by Tadasu Takamine, a once a member of the performance troupe Dumb Type, is a video series reenacting people’s conversations after the disaster. Here 13 videos lasting a few minutes each focus on interactions at food shops in and around Mito. Staff and customers have polite but strained discussions, circling around the subject of the disaster’s impact on local lives.

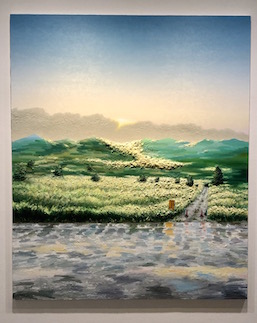

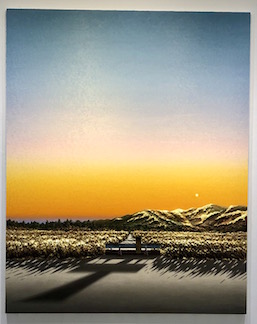

Akira Kamo’s richly textured oil paintings show pastoral scenes of Fukushima Prefecture. These unpopulated, eerily peaceful landscapes are marked by barely noticeable “Do Not Enter” signs. With these works, Kamo, who has said he views “painting and surviving as synonymous,” wanted to evoke the invisible and question the impact of human beings, even in their absence.

Artist and film director Hikaru Fujii produces video installations that respond to contemporary social issues. In “The Classroom Divided by a Red Line,” he has updated U.S. educator Jane Elliott’s school experiment about racial discrimination to reflect issues of prejudice facing people from Fukushima. Fujii directed the film, in which Mito school children played active roles.

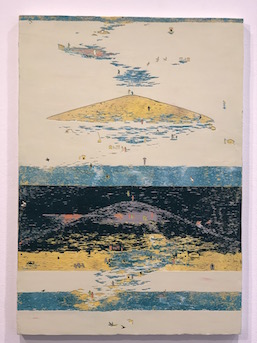

Makiko Satake’s multi-layered paintings depict areas affected by the tsunami. In one work, people are shown fleeing to shelter, while others in the same scene are fishing. These images suggest that the disaster is just one part of the histories of these places.

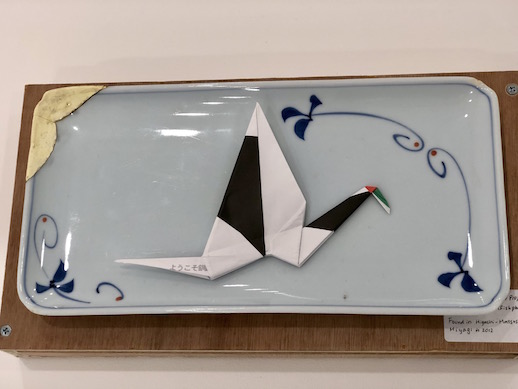

For her “Repairing Earthquake Project,” the Netherlands-based Japanese artist Nishiko collected objects from the Miyagi coast damaged by the tsunami. She then repaired and found “foster parents” for them in the Netherlands, recording conversations about the caretakers’ feelings towards them for Japanese audiences. One participant, a “guardian” for a serving dish, said that he wanted to take part in the project because “in principle, the object becomes a being.”

Don’t Follow the Wind is an art project in the Fukushima nuclear exclusion zone. This area is still closed to the public, meaning that the artworks cannot be seen until the blockade is lifted. Initiated by Chim↑Pom, the project involves 12 artists, some of whom present works here. Artist Meiro Koizumi interviews a man who used to live in an area heavily affected by the disaster, engaging with his emotional responses to the destruction. Aiko Miyanaga presents glass sculptures manifesting her belief in the arbitrariness of boundaries and the interconnectedness of human lives.

The creative response to March 11, 2011 has been too vast and diverse to comprehensively survey in a single show. Still, the offerings of “Imagining in the 10th Year” manage to represent a range of genres and approaches. The tones of these works vary from quietly meditative to acerbic, capturing some of the waves of emotion in the decade since the disaster. Significantly, the final room in the exhibition invites viewers to write and call in with their impressions of the show and memories of lived experienced. As this exhibition attests, the conversation about 3/11 has only just begun.