Aomori and Its Artists

The Aomori Museum of Art, a 3.5-hour bullet train ride from Tokyo, ranks among Japan’s most superbly unique destinations for any admirer of Japanese art. In addition to its extensive Japanese art collection, AMOA’s highlights include a performing arts space with wall-sized paintings by Chagall, just one artist in its lineup of international masters such as Klee, Picasso, Kandinsky, Redon, Matisse, and Rembrandt. This report looks at the museum’s architecture and its remarkable collection of work by artists with connections to Aomori Prefecture.

Designed by Jun Aoki, the building is a striking example of contemporary architecture. This above/below-ground compound next to an archeological site unearthing relics from the Jomon period is made up of well-defined yet open and interconnected spaces with towering ceilings. It has no predetermined route from entrance to exit.

Art director Atsuki Kikuchi created AMOA’s tree emblem as a symbol of the museum’s place within nature.

The colors of the inside and outside walls are invariably white or brown, an aesthetic choice referencing the earthen trenches of the Jomon grounds and the concepts of old and new.

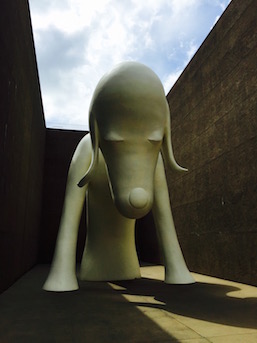

Watching over AMOA is “Aomori-Ken” (Aomori Dog), contemporary artist Yoshitomo Nara’s iconic canine standing 8.5 meters in height.

This hound appears in various forms around the museum, from the three-meter ‘Prototype of A to Z Memorial Dog,’ to a litter of pups roosting inside ‘New Seoul House.’

Early works by Nara (b. 1959), one of Japan’s most celebrated contemporary artists, are displayed along with pictures and sculptures of his notoriously cute and churlish characters.

Nara is among the artists with ties to Aomori showcased for their body of work distinct within the Japanese canon. Another renowned Aomori-born artist is the woodblock printmaker Shiko Munakata (1903–1975), a key figure in the mingei folk art movement.

Munakata’s ‘A Flower Arrow’ (1961), a six-meter-long series of panels, expresses his desire to spread culture from northern Japan to the rest of the country, countering the widely held view that culture originated in the south. Here the beauty of culture, represented as the flower, is sent forth with arrows.

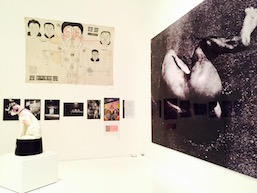

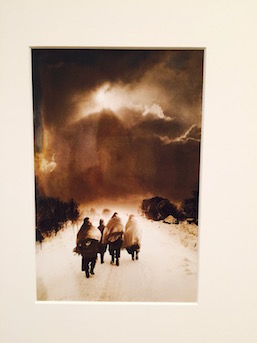

The films and underground theater productions of Shuji Terayama (1935–1983), from the height of the counter-culture movement of the 1960s–1970s, have enjoyed something of a renaissance in recent years. At AMOA, wooden crates recreating those used in Terayama’s performances are integrated into his exhibition space, which includes LP records for the soundtrack of ‘Throw Away the Books, Let’s Go Into the Streets,’ the 1971 experimental film considered his one of his most important works.

The design of Terayama’s room also gives a nod to the architecture of Aomori houses, seen in a glass wall resembling the “double-genkan” foyer many homes have to keep out snow.

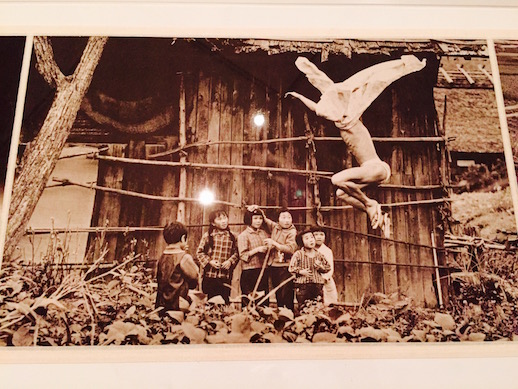

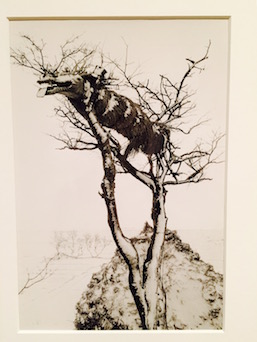

Choreographer Tatsumi Hijikata (1928–1986), co-founder of the avant-garde postwar dance style Butoh, is another artist with a northern Japanese background (Hijikata was born in Akita Prefecture).

Butoh overturned conventional Japanese dance practices and aesthetics by emphasizing primal and unconsciously expressive movements, exemplified in photographs of Hijikata leaping half-naked through the air or curled up in a ball, as if for warmth. The latter posture contrasts starkly with traditionally Western poses extending the body skyward. Hijikata’s exhibit, which includes works from the Keio University Art Center Hijikata Tatsumi Archive, also features other groundbreaking and rebellious mid-century artists such as Eikoh Hosoe, Shuji Terayama, Yokoo Tadanori, Genpei Akasegawa, and Natsuyuki Nakanishi.

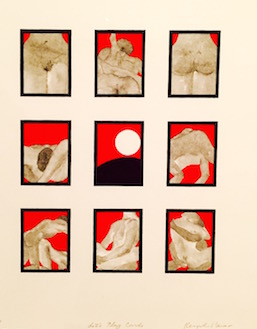

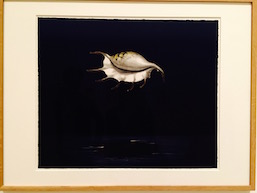

Aomori-born Kenjilo Nanao (1929–2013) was a printmaker and painter who worked mainly in California. His poetic, sensual lithographs with rich colors and natural symbolism have been compared to Shunga erotic prints.

Kojin Kundo (1915–2011) blended Nihonga and Western painting techniques in fantastical scenes incorporating organic motifs. Expressing “the imagery of the heart,” Kundo participated in the postwar movement to establish new artistic styles.

Tadahiro Ono (1913–2001) was a Venice Biennale artist and member of the “junk art” movement who worked with Shiko Munakata. He made abstract sculptural paintings with familiar objects such as the sandals and other belongings of his deceased wife.

Japanese monster aficionados will enjoy the work Tohl Narita (1929–2002), a sculptor and designer known best for his characters in the ‘Ultraman’ TV series. AMOA’s collection is home to illustrations of Narita’s delightfully bizarre creatures, as well as his sculptures demonstrating an undying interest in producing imaginative new forms.

Photographer Ichiro Kojima (1924–1964) captured with elegiac beauty the mysticism of Aomori’s harsh terrains in images of its farms and villages during the 1950s and 1960s.

The Aomori Museum of Art is currently closed for repairs, but will reopen in mid-March, 2016.