An Orchestrated Theater of Dichotomies

The Mori Tower is as busy as ever, with children impatient to visit the Sky Aquarium and couples pouting because the Sky Deck has been closed due to lightening, which is indeed making an impressive show above the endless cityscape.

The opening act of this exhibition — an installation titled Them and Us, Us and Them (2000) — is no less impressive, set in a bright and fantastical atrium. Here, taxidermy birds, their heads stuffed inside those of colorful and cartoon-ish, decapitated stuffed animals, swing from perches made of looking glass. Look up at one of these double-stuffed birds and you will see yourself looking back. I was struck by how the contrast echoed the silent world inside the peaceful white gallery walls versus the chaos reigning outside.

The French artist titles many of her pieces with dichotomies: Inflating, Deflating; Spoken, Unspoken; Men I like, don’t like. The language the museum uses to describe her works similarly employs pairs of opposing concepts: childhood and adulthood, humor and fear, protection and destruction, religion and secularity, nature and artifice…

If anything, these contrasts show the limits of language to adequately describe the scene at hand. Messager works within the museum’s cavernous warrens, connecting, and existing between the two ends of so many spectrums and it is from this place, I believe, that she deploys “The Messengers.”

The exhibition spans her forty-year career, including early pieces characterized by her tendency to collect things and more recent fantastical works, a glimpse at her notebooks, and an excerpt from her Golden Lion Award winning Casino installation created for the 2005 Venice Biennale. Seen in this scope (this is Messager’s first solo exhibition in Japan) her body of work is altogether captivating.

There are complex mechanical installations that fill whole rooms, such Articulated, Disarticulated (2001-02), an orchestrated theater of roughly hewn but mechanized marionettes of stuffed animals, some of which heave up and down as though breathing. There are also simpler, more personal works, such as My Trophies (1986-88), a series of black and white photographs of illustrated palms of hands, followed by the same word written over and over again, simultaneously like a naughty child and one being condemned to work off a sin, in colored pencil on the gallery wall. You’ll notice the changing handwriting and learn at the end, where a video of the installation process plays, that local art students lent their hands for this piece.

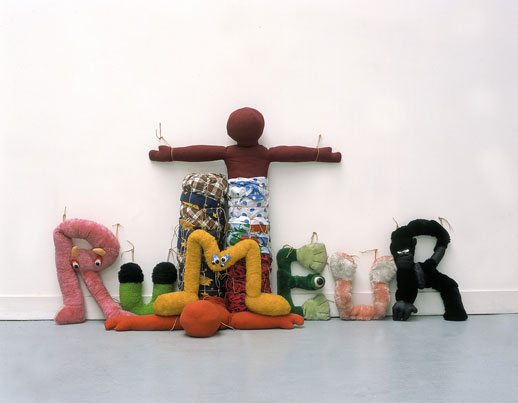

Messager is most well-known for her use of less then typical media: yarn, dresses, books, colored pencils, dead birds, even body parts (or photographs of) are commandeered as canvases, but above all there are the stuffed animals. Well-loved and worn, or crude replicas made from stockings, these children’s toys are employed as effigies, impaled with colored pencils, skinned and pinned to the wall like scientific specimens, reshaped into letters spelling out messages, and dissected and reformed into imaginary creatures, hanging limp from the ceiling. This palette combines to form a montage of a discarded childhood, a coming of age ritual played out in infinite variation.

Her work is ultimately rooted in the mundane world: the artist accumulates this diverse collection of materials from those close to her or places she has happened across; flea markets, it seems, are a rich source of retired stuffed animals. The familiarity of these materials, which we know more intimately by touch then by sight, inspires a palpable sense of closeness to Messager’s works. This tangibility has the power to draw the viewer quite literally: a Japanese couple next to me was scolded for touching a stuffed cow. It goes without saying that museum-going adults are rarely moved to break the understood barrier between destructive fingertips and important artistic constructions.

Rebecca Milner

Rebecca Milner