An Introduction to ‘Mono-ha’

Nobuo Sekine, 'Phase - Mother Earth' (1968)

‘Mono-ha’ refers to a group of artists who were active from the late sixties to early seventies, using both natural and man-made materials in their work. Their aim was simply to bring ‘things’ together, as far as possible in an unaltered state, allowing the juxtaposed materials to speak for themselves. Hence, the artists no longer ‘created’ but ‘rearranged’ ‘things’ into artworks, drawing attention to the interdependent relationships between these ‘things’ and the space surrounding them. The aim was to challenge pre-existing perceptions of such materials and relate to them on a new level.

The name ‘Mono-ha’ was actually more of a label applied to the group, and its origins are as elusive as any precise definition of the movement.1 Usually translated rather awkwardly as ‘school of things’, it is a misleading name: Mono-ha works are as much about the space and the interdependent relationships between those ‘things’ as the ‘things’ themselves. Making the viewer become aware of his position in relation to the work is also something which the Mono-ha artists aimed for.

And as far as ‘groups’ go, Mono-ha was a fairly loose one: something of a conglomeration of interlinking relationships between the various artists involved. Ideologies were not necessarily shared by all members of Mono-ha, so it was not a coordinated ‘movement’ as such. Roughly speaking, Mono-ha is thought of as centring around Nobuo Sekine, Lee Ufan, Katsuro Yoshida, Susumu Koshimizu, Koji Enokura, Kishio Suga, Noboru Takayama and Katsuhiko Narita. Below I will give a simple introduction to some of their key works and the ideas behind them.

Nobuo Sekine

The emergence of Mono-ha has its roots in many social, political and cultural factors of the 1960s, and to trace its origins in detail is a complicated matter. However, the moment that is most often viewed as Mono-ha’s starting point came in October 1968 with Sekine’s ‘creation’ of the work Phase – Mother Earth in Kobe’s Sumarikyu Park for the First Open Air Contemporary Sculpture Exhibition. The work consisted of a hole dug into the ground, 2.7 metres deep and 2.2 metres in diameter, with the excavated earth compacted into a cylinder of exactly the same dimensions. Sekine described the moment when they removed the mould:

“Faced with this solid block of raw earth, the power of this object of reality rendered everybody speechless, and we stood there, rooted to the spot… I just wondered at the power of the convex and concave earth, the sheer physicality of it. I could feel the passing of time’s quiet emptiness… That was the birth of ‘Mono-ha’.”2

Topology was a key concept in Sekine’s work of the time; it gave a severe jolt to the foundations which supported ideas of three-dimensionality in art. Topological shapes are not regarded as quantifiable entities, but rather seen as ‘phases’ extendable over contraction and expansion. Sekine’s works since the ‘Phase’ series have also been influenced by Eastern philosophy, in particular Zen, producing an unusual fusion of Western mathematics and ancient Eastern aesthetics and philosophy.

Lee Ufan

In November 1968 Sekine met the Korean-born artist Lee Ufan (b. 1936), who was soon to be of central importance to Mono-ha and the articulation of its ideas. Lee had studied ‘Asian thought’, including the philosophy of Laozi and Zhuangzi and after moving to Japan in 1956, had studied modern Western philosophy at Nihon University. Lee recognised the progressiveness of Sekine’s ideas and admired his work, whilst Sekine found in Lee a theoretician to support his artistic practice and views of art.

Lee, in a similar way to Sekine, took natural materials such as stone, glass, rubber, iron plates and cotton and presented them in juxtaposition, so as to reveal the physical materiality of the work and allow the materials to establish their own relations independent of artistic intervention. Lee’s work Phenomenon and Perception B (1968), the title of which he later changed to Relatum consists of a sheet of glass that has cracked under the weight of the large stone block placed on top of it. About this work, he explained:

“If a heavy stone happens to hit glass, the glass breaks. That happens as a matter of course. But if an artist’s ability to act as a mediator is weak, there will be more to see than a trivial physical accident. Then again, if the breakage conforms too closely to the intention of the artist, the result will be dull. It will also be devoid of interest if the mediation of the artist is haphazard. Something has to come out of the relationship of tension represented by the artist, the glass, and the stone. It is only when a fissure results from the cross-permeation of the three elements in this triangular relationship that, for the first time, the glass becomes an object of art.”3

Kishio Suga

Like Lee, Suga Kishio (b. 1944) made works that were not so much about their material qualities as their ‘situation’. His work almost never juxtaposed differing materials in the same way as other Mono-ha artists did. Instead, one can say that through relationships and arrangements he studied how things exist.

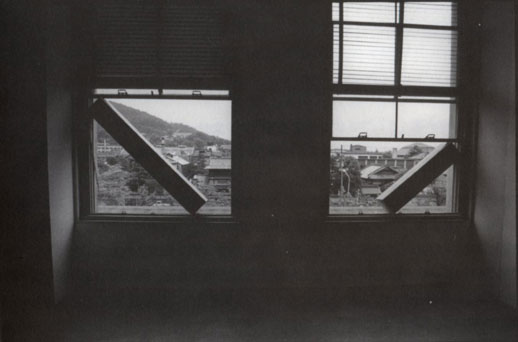

One of his well-known works which typifies this concern of his is The Laws of Situation (1971) in which he balanced a number of stones along the middle of an approximately seventy-foot long plastic board and set it afloat in a lake in Ube. Also, in Limitless Condition (1970), two pieces of wood were placed diagonally, propping open two adjacent windows of a back staircase at The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto. Suga achieved a delicate balance in his placing of the wood, which having drawn the viewer’s attention to the objects themselves, almost inescapably invite scrutiny of the materials and forces surrounding them. Although the situation is essentially transitory, there is a sense of intangible wholeness in the work.

Koji Enokura

For the 1971 Biennale de Paris, Koji Enokura (1942 – 1995) exhibited a work entitled Wall, consisting of a concrete wall roughly 3 metres high built between two trees about 5 metres apart. The hard, physical intervention in a natural space drew attention not only to the relationship between those two trees, but to all the others in the surrounding environment as well.

For Enokura, it was truly the ‘material as a medium’ in its roughest possible form that interested him. Early on he used oil or grease to soak paper or walls so as to reveal the materiality of the surface covered. He also sought to verify himself through his relationship with the surrounding world; in his words “what I wish to explore is the tension between body and matter, which in my mind would serve as proof of my own existence”.4

Susumu Koshimizu

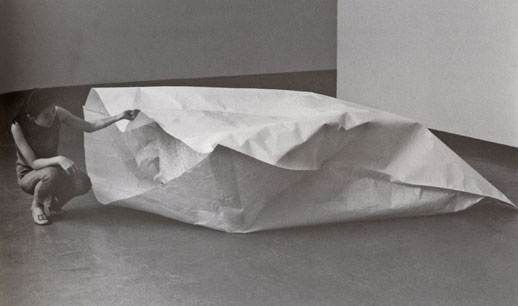

Conceptually, the work of Susumu Koshimizu (b. 1944) bears resemblance to both Lee and Suga’s. Like Suga’s, his work focuses on the qualities inherent to, but not visible in an object. And yet, like Lee, he shows concern for the materiality of objects; a desire to expose the fundamentals of sculpture, often revealed through juxtaposition. In his work Paper 2 (later renamed Paper) (1969), he placed a large stone inside an even larger envelope of Japanese paper, open on one side. The viewer is able to look into the envelope and, in the sculptural context of relating interior structure to exterior form, is confronted with the sheer size and solidity of the stone in contrast to the thin membrane of paper that covers and conceals it.5

Noboru Takayama

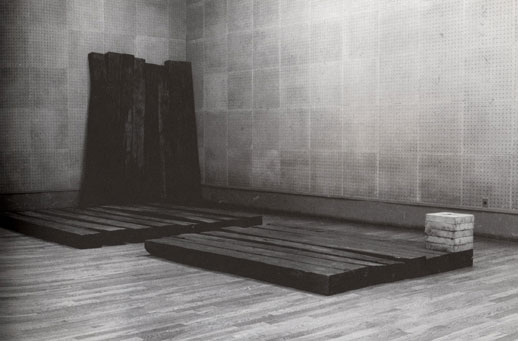

Takayama made works that differed from those of other Mono-ha artists in that they more overtly addressed the conceptual associations made with certain materials, rather than simply presenting those materials ‘as they are’. Most notable is his use of railroad ties as a recurrent source of expression. They were not ready-made materials: from the preparation of raw materials such as beechwood and creosote to the burning of their surfaces, the works required a certain amount of time to produce. For him, railroad ties have specific connotations of the forced labour propagated in Japan’s colonies during World War II. While Takayama may not have been conscious of it at the time, this choice of heavy, meaning-laden material is now perceived as a reflection of the socio-political unease of the time, when anti-Vietnam war and anti-American protests dominated student campuses.

Katsuhiko Narita

Similar to Takayama, it is unclear to what extent Katsuhiko Narita (1944 – 1992) can be called a Mono-ha artist. He became renowned most for his work Sumi, first exhibited at the Biennale de Paris in 1969, which consisted of a line of large pieces of charcoal, aiming to eliminate the act of ‘making’ as much as possible. The burning of the wood left the creative process up to nature and emphasized its material presence. However, his work as a whole deals more with spatial perception than the materiality of things. In spring 1969, at the ‘9th Contemporary Art Exhibition of Japan’ Narita simply coiled a steel belt around a dividing wall in the exhibit hall, and in his solo exhibition at the Muramatsu gallery he shrank the gallery space by setting up temporary walls.

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, Mono-ha can only loosely be defined as a group or unified movement. This is only a basic introduction to each of these artists’ activities; the more one studies each artist’s career, the more the differences in their working techniques and conceptual approaches becomes clear. As research in the field of postwar Japanese art history expands, art historians and critics are increasingly debating the formation, definition and evolution of the phenomenon that was Mono-ha. Ironically, the more retrospective discussion and commentary there is on Mono-ha, the more discrepancies emerge between what the artists said at the time and what they say now, and what others said then and say now, making it at times hard to tell what the truth is. The exhibition ‘Reconsidering Mono-ha’ held at the National Museum of Art, Osaka from October to December 2005, and ‘What is Mono-ha’, held at Beijing Tokyo Art Projects in May 2007 were the latest efforts to address Mono-ha’s role in the history of Japanese contemporary art.

While the convergence of these various artist’s ideas and practice was a relatively brief one, lasting essentially from 1968 to 1972, and despite the debate over how to define Mono-ha, what is clear is that it had enough force to act as a catalyst for a major change in Japanese contemporary artistic expression. As Yasuyuki Nakai wrote in his essay for the ‘Reconsidering Mono-ha’ catalogue, “Up until 1968, and perhaps even 1969, all the changes in Japanese art after the war and the following modern era, were little more than an imitation of the West. Outstanding individual artists had no choice but to build on their own achievements”. By rejecting the Euro-American avant-garde of the preceding decade, Mono-ha paved the way for the Post Mono-ha generation to find their own artistic practice. As Janet Koplos explains in her article ‘The Two-Fold Path: Contemporary Art in Japan’, many young artists of the mid-’70s rejected Mono-ha, turning towards turning towards fabrication, colour and subjectivity.7 While such a shift may sound routine, it was in fact a major turning point in for Japanese contemporary art, since the rejection of Mono-ha ideas marked the first time that young Japanese artists were specifically addressing a Japanese art movement rather than responding to a Western style filtered through its Japanese practitioners.

—

1 Tatehata, A., (2001) ‘Mono-ha and Japan’s Crisis of the Modern’ in Mono-ha, exh. cat. Cambridge: Kettle’s Yard.

2 Sekine, N., Aru kankyô bijutsuka no jiden, unpublished manuscript.

3 Munroe, A., (1994) p.265, Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky, exh. cat. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

4 Okada, K., (1995) p.55, ‘Gendai bijutsu he no toi: busshitsu kara no tankyû to monoha wo megutte’ in 1970nen – busshitsu to chikaku: monoha to kongen wo tou sakkatachi, exh. cat. Tokyo: Yomiuri Shimbun & The Japan Association of Art Museums.

5 Groom, S., (2001) p.15, ‘Encountering Mono-ha’ in Mono-ha, exh. cat. Cambridge: Kettle’s Yard.

6 Okada, K., (1995) p.105, ‘Gendai bijutsu he no toi: busshitsu kara no tankyû to monoha wo megutte’ in 1970nen – busshitsu to chikaku: monoha to kongen wo tou sakkatachi, exh. cat. Tokyo: Yomiuri Shimbun & The Japan Association of Art Museums. Matter and perception 1970 mono-ha and the search for fundamentals

7 Koplos, J., (1990) ‘The Two-Fold Path: Contemporary Art in Japan’ in Art in America, New York: Brant Art Publications, Inc.

Ashley Rawlings

Ashley Rawlings