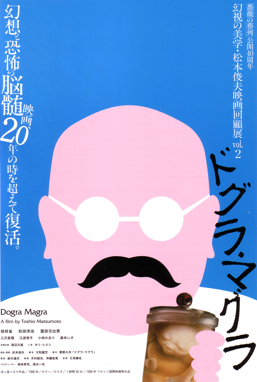

Aesthetics of Hallucination

With their established codes and logic of expectation, genre films have proven a fertile ground for experimentation. The horror genre in particular allows filmmakers great latitude in exploring uncanny or illogical motifs with spectacular visuals and unusual narrative forms. Such is the case with Toshio Matsumoto’s Dogura Magura (1988), but which presses beyond mere play with conventions, entering genuinely uncharted waters. Set in Taisho 15 (1926), Dogura Magura recounts the story of Ichiro Kure (Yôji Matsuda), a young medical student who awakens in the Kyushu Psychiatric Hospital, unsure of who and where he is. As doctors Wakabayashi (Hideo Murota) and Masaki (the late rakugoka Shijaku Katsura) treat his amnesia in an attempt to recover Ichiro’s memory, we learn that both his mother and fiancée have been murdered. Who was the killer? Perhaps Ichiro’s memory holds the answer.

As a horror film, Dogura Magura is unconventionally subdued. There is violence and there are grotesque elements, but no smash cuts, chase scenes, hockey masks, evil children, or similar tricks of the trade. There is, rather, a labyrinthine plot brimming with curious ideas and challenges to our sense of reality. In a sense, then, the violence unfolds at a more conceptual level. Where the classical horror film has been christened “gothic”, Dogura Magura might be more properly related to the baroque. Much of this comes straight from Yumeno Kyûsaku’s novel Dogura Magura (1935), which Matsumoto has adapted rather neatly for the screen. Widely regarded as a masterpiece of surreal fiction, Kyûsaku’s novel blends literary modernism with “erotic-grotesque nonsense” [ero-guro-nansensu]. It has been associated with the genre of so-called “irregular detective novels” [henkaku tantei shôsetsu], which found its origins in the stories of Edogawa Rampo during the 1920s. Indeed, the film unfolds like a detective story around the identity of the murderer.

Through a rich structure of flashbacks, Dogura Magura explores the problem of characters who lack a stable identity. Told from innumerable points in time, the narration presses the limits of our ability to linearize the story. As Dr. Masaki probes Ichiro’s loss of identity, he creates a film with the boy as its protagonist, explaining that the plot of this film-within-the-film concerns “the brain searching for itself”. Here, Matsumoto expands the novel’s meta-fictional aspects (within Kyûsaku’s novel, the protagonist is shown a mystery novel entitled “Dogura Magura”) using meta-cinematic elements. When Dr. Masaki presents his film, Ichiro proves unable to watch himself on the screen, asking “Is it really me?” Rather than telling the story of a character’s fight for survival, love, or redemption, Dogura Magura plunges us into the discovery of a character’s identity, with all of its attendant uncertainty. As in his earlier film Demons (Shura, 1971), Matsumoto freely interweaves subjective mental states into the narrative. We enter Ichiro’s delusions, and if at moments this is clear (as when he imagines himself in an auditorium, lecturing on the physiology of the brain) at other moments the separation between fantasy and reality becomes grey.

Given Ichiro’s loss of memory, we must rely on the accounts given by Wakabayashi and Masaki, but it is soon evident that they are embroiled in a complex professional rivalry. How does the doctors’ drive for knowledge collide with their sense of moral responsibility? Or, to state it more simply, and in terms that recall the myth of Oedipus, where does the desire for knowledge end? A complex, multi-layered work, Dogura Magura expands on Matsumoto’s earlier narrative experiments, posing the problem of cinematic pleasure, prompting us to reflect on modes of storytelling that disorient and disconcert, and on the contours of our desire for the codes of certitude.

M. Downing Roberts

M. Downing Roberts