A View from the Couch

Drawn from a collection of over 2,000 artworks, the psychiatrist Ryutaro Takahashi’s private collection of contemporary Japanese art has recently gone on display at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery. Consisting of 140 works by 52 different artists, it’s the first time that these works have been shown together like this. What began almost twenty years ago as a way to decorate the walls of his clinic with stimulating imagery, soon outgrew the premises. In an interview posted on Azito blog, the ambitious art collector recalls:

My initial idea was silly. […] I repeatedly expanded my clinic in order to get more exhibition space. It was my […] dream to extend the clinic with every item that I added to my collection. From around the tenth extension, I realised I wouldn’t be able to continue that stupid game.

And so, after almost two decades of clinic and collection expansions, “Mirror Neuron” cherry-picks a selection of works that describe a development of contemporary art in Japan.

While Takahashi only begun collecting in 1997, several years after the bubble economy burst, “Mirror Neuron” name-checks some of the best known Japanese artists working today. Yayoi Kusama, Takeshi Murakami, Yoshitomo Nara and Makoto Aida are among the artists shown. Art historically, the collection also boasts works by Kishio Suga and Lee Ufan and so represents two of the key figures in the 20th-century art group Mono Ha. Encouragingly, the inclusion of more recent artists like Miwa Yanagi, Kohei Nawa, Tabaimo are also on show. What makes Takahashi unique among collectors is that he focuses entirely on Japanese art.

“Mirror Neuron” isn’t a typical survey show. Being the collection of an individual, it’s more personal than most survey shows. Nor is it exhaustive; but it doesn’t try to be either. For practical purposes, Takahashi favours two-dimensional works. The only exception is a colossal wooden sculpture by Yasuyuki Nishio. For anyone hoping to see performance, installation, video or new media art, this show could disappoint, but for those interested in works of art made in more conventional media, often with figurative basis or with discernible technical proficiency, Takahashi’s collection is an excellent crash course in contemporary Japanese art.

Thematically, “Mirror Neuron” takes its title from the field of neuroscience. A mirror neuron is one that fires both when an animal acts and when an animal observes the same action performed by another. Basing the exhibition’s theme on a term that empathises with memetic behaviour serves to place it within the context familiar to the collector’s professional sphere, while also going some way to reflect Takahashi’s preference for technical competency too.

Unconventionally, the works on display in “Mirror Neuron” aren’t bogged down with explanations. This is to be applauded. Limiting the information next to each exhibit allows the work to be read as objects or images in themselves. In this sense, Mirror Neuron could be said to have populist appeal, but it’s a positive attribute that’s only likely to broaden the audience for contemporary Japanese art.

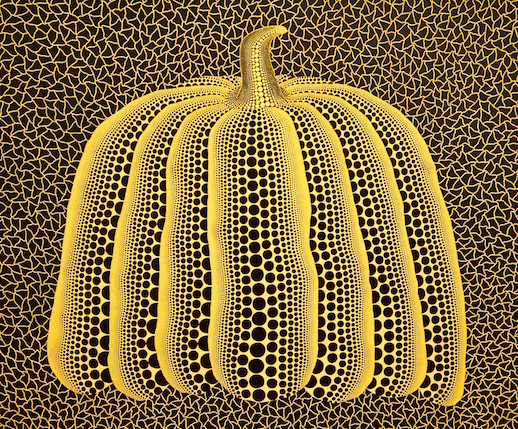

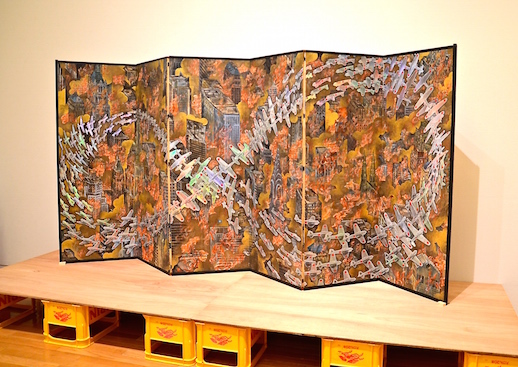

Beyond Yayoi Kumama’s graphically striking Pumpkin (1990), past the dissident stares in Yoshitomo Nara’s angsty portraits or the bubbling brain stew of Tabaimo’s ink drawing, A Crime in the Kitchen (2003), one of Takahashi’s most significant acquisitions is A Picture of an Air-Raid on New York City (War Picture Returns) (1996) by Makoto Aida. Painted on byōbu, or folding screens, the artist installs the piece by placing it on wooden boards stacked on beer crates; managing to elevate and diminish its status at once.

A Picture of an Air-Raid on New York City demonstrates how Japanese artists use tradition to re-situate narratives in contemporary contexts. Although the form recalls the splendour that folding screens have, the subject matter has been subverted to serve an alternative vision. Made some years before the terrorist attacks on the twin towers, Aida creates a devastating vision of the Manhattan skyline engulfed in smoke, and under siege from Japanese World War II-era fighter planes. As the Chrysler building peaks its way through the plumes, Zero fighters form a figure-eight in the foreground.

Aida frequently tackles national taboos. With a high degree of technical expertise, he borrows freely from a variety of styles and sources. Whether it’s traditional Japanese painting, former political propaganda or contemporary manga, Aida has established a reputation for distilling exaggerated, often disturbing visions, to reveal darker images of the national psyche.

It’s easy to interpret A Picture of an Air-Raid on New York City as an elaborate revenge fantasy made in a historic style, as though belonging to an alternative past, but while it is contentious it’s also worth noting that the same artist has depicted piles of dead Japanese salarymen piled high upon one another (Ash Colour Mountains from 2009-11) like discarded components from Japan’s corporate world, and so Aida’s visions are not without self-criticism.

My only criticism of “Mirror Neuron” is the exhibition text’s claim to be ‘holistic’ in how it examines the development of contemporary art in Japan. This claim seems to suppose that all Japanese artists are dipping into a national unconscious, all somehow channelling the same anxieties. Thankfully, the artworks here are too diverse to resist singular categorisation. It’s the variety in Takahashi’s collection that makes it absorbing to see.

While choosing to start acquiring art during the late nineties probably assured Takahashi some shrewd investments, it’s also worth remembering that the artists’ reputations are based, in part, on these investments. Although it may appear an impressive list of names, some of the best known Japanese artists working today are known as such precisely because their work was bought by the renowned collector in the first place. Without the foresight of collectors like Takahashi to bolster artistic practices, shows like “Mirror Neuron” wouldn’t happen and the view from the couch would be bare.

Nick West

Nick West