A Life of Its Own

In January London-based artist Ami Clarke travelled to Tokyo to install two video works in The Container, a gallery space located in a hairdressing salon in Nakameguro. Whilst in Japan she also launched her free of charge publication “UNPUBLISH”, which can be picked up at the exhibition, and delivered a talk at Konno Hachiman Shrine (January 25), mainly discussing her passion for diagrams, her preoccupation with how the cosmos functions, and past and present working practice.

An artist who began as a sculptor and has created work in a variety of media throughout her career, she frequently incorporates pre-existing material at the centre of her projects via a considered process of interrogative mediation. More recently, it is filmic texts and the presentation of written communication that have become increasingly prominent in her oeuvre. With this it is worth noting that Clarke is also the founder of Banner Repeater, a reading room and project space located on the platform of Hackney Downs railway station, East London. From here artistic texts are distributed to the public en masse and information laid directly into the hands of weary commuters, their target audience. The process of denoting “knowledge” and the questions of how “knowledge” is disseminated and then acquired on an individual level are at the forefront of her creative practice and the issues addressed by the works now on show.

In the current exhibition entitled “Be Seeing You”, Clarke’s process of re-appropriating matter as a way to expose the underlying relationships and assumptions that original texts precariously subsist upon is in full force. Broadly acknowledging and often highlighting the original sources for her works, and meanwhile discussing the manner in which she discovered and subsequently altered them, Clarke’s way of working lauds an overwhelming transparency.

The main video projection is telling of both Clarke’s fascination with the popular late Sixties British spy fiction TV series “The Prisoner” and her ongoing investigation into the nature of how information is handled in the age of modern technology and advanced capitalism. It is not necessary for one to have knowledge of “The Prisoner” prior to visiting the exhibition, but having a grasp of the themes the series explores may provide a useful point of entry for this particular work.

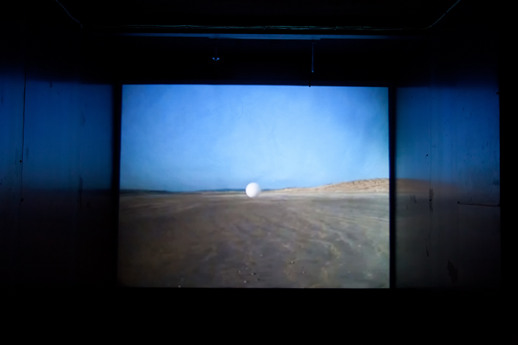

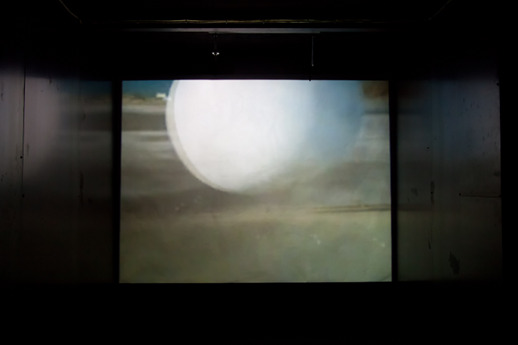

In the first episode the main protagonist/prisoner awakes in an anonymous and isolated village, having been abducted for interrogation following his abrupt resignation from a secret agent role. He angrily states, “I will not make any deals with you. I resigned. I will not be pushed, filed, stamped, indexed, briefed, debriefed or numbered. My life is my own.” Arguably this sentiment resonates strongly with the video work. Primarily featuring footage of ‘Rover’ (a large, white, balloon-like object that forcibly controls non-compliant inhabitants) and rhythmically edited scenes of varying depictions of light, the nature of the changeable spherical images represented in this large projection are laid open for questioning. Re-presenting multiple manifestations to explore the construction of Rover specifically, taken from both the original TV series and the 2009 U.S. mini-series, Clarke makes a bid to analyse an object that she admits has been a long-term obsession of hers. However, in making this video, more than ever the plasticity of the object and the impossibility of its movement becomes increasing opaque, as she is the first to claim; whilst the filmic illusion is broken down in the reconfiguring of the stock footage, the absurd and somewhat alarming nature of the circular image on screen is retained. Rather than briefing or debriefing the audience and allowing them to “know” the object represented, she turns the interrogative strobe back onto the viewer, rejecting and challenging their desire for a single channel of explanation, and instead allows it to have a life of its own.

Furthermore, Clarke also exposes the fallacious nature of the chimeric one-directional relationship between the viewer and the screen by demonstrating that such an archaic, singular standpoint is merely one of a multiplicity positions that the viewer may choose to inhabit when encountering a filmic text. In an age of ever more refined technology, direct experience and interaction with art has become increasingly treasured, something that is adamantly avoided in popular filmic tradition. For this reason, the container space itself is also significant. With a rather odd and disconnected atmosphere, it holds the viewer at a tension as to whether they are situated in a submersive environment or actually at somewhat of a remove from the projected work. Whilst stood awkwardly in an unevenly darkened and rather cramped steel shell – there is no indication of where is best to stand – the sound in the film also comes and goes. At times it is rather loud, a mixture of the stock music and actors’ voices, though more often than not it is barely audible. The extraneous noises from the salon are consistently perceptible and often drown out the more dulcet film score. This makes one unable to avoid the artificiality of the situation and the incongruous nature of the video and the screening set up – the illusion is broken.

What is most interesting is that for Clarke it is the plurality of manifestations and perspectives, which the illusory dimension so reliably denies or disavows, that are of concern. “UNPUBLISH”, some of the pink pages of which are enlarged and pasted up inside The Container, could be considered as an unconnected yet occasionally converging exploration of similar themes. Openly addressing the act of deleting information as an attempt to re-write history, Clarke playfully takes the recent case of U.S. solider Bradley Manning and questions the concept of “un-publishing” information. For, as in the films, she appropriates pre-existing material and re-works it in a way that allows audiences to dispute the often singular authority that a text is assumed to have, granting it license to continue to exist with a life of its own.

Jessica Jane Howard

Jessica Jane Howard