The Year That Changed It All

The second half of the 1960s was an exciting period of epochal world events in which students, workers and intellectuals questioned everything – from social hierarchies to the political system and cultural dogmas. Even Japan experienced turmoil. In particular, a new generation of artists pushed their respective fields beyond commonly accepted standards. The Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography’s current exhibition, “1968 Japanese Photography”, chronicles the events through which Japanese photographers began to challenge traditional approaches to photography; many of whom came up with novel answers to the seemingly simple question, “what is a photograph?”

1968 in particular was a turning point in the history of Japanese photography, starting with the “A Century of Photography” exhibition in which The Japan Professional Photographers Society explored the way Japanese photography had evolved in the previous 100 years. The organizers, headed by Shomei Tomatsu and including among others Koji Taki and Takuma Nakahira, reassessed the evolution of photography up to that point, and its role in shaping Japanese society.

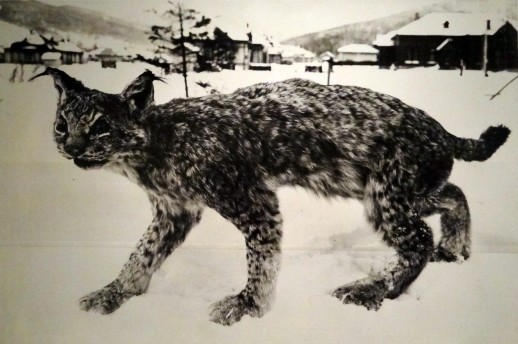

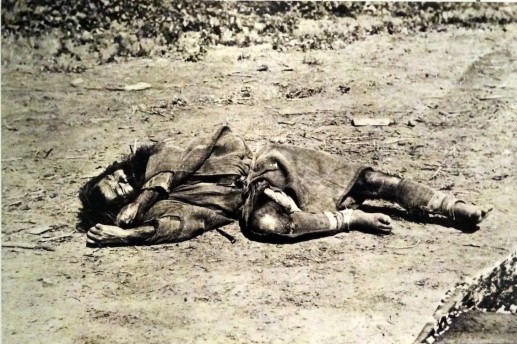

The exhibition features a number of vintage works that foresaw, with their provocative and feral images, the revolution to come.

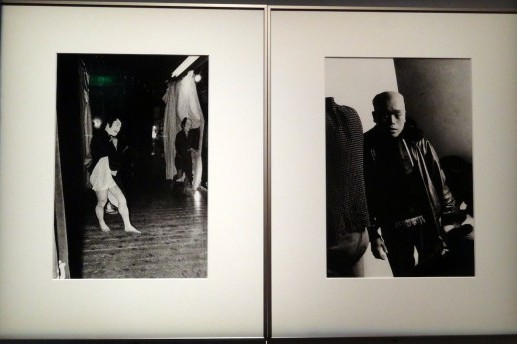

Among the artists who showed an interest in new subjects were Yutaka Takanashi, who around the same years produced the “Tokyoites” series…

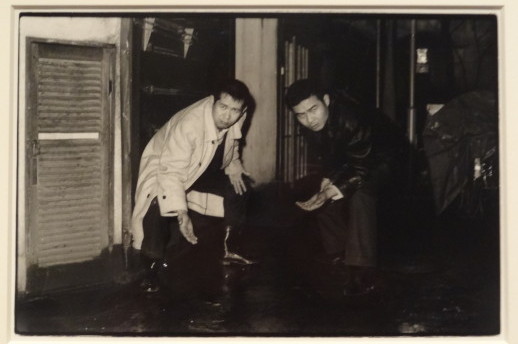

… and Daido Moriyama who portrayed the world of the stage in his “Japan Theater” series.

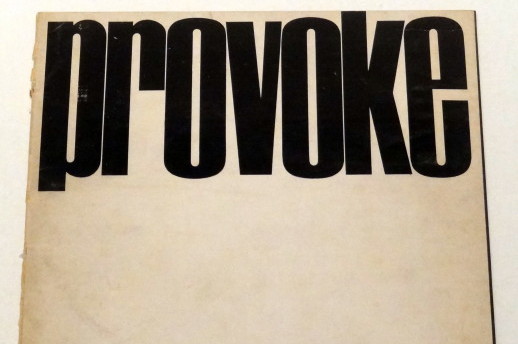

In 1968, Taki, Nakahira and Takanashi, together with Takahiko Okada launched Provoke Magazine. They were later joined by Moriyama.

Breaking with established photographic canons, Provoke championed a new rougher style characterized by blurry, sometimes sideways images, that provided a new aesthetic sense to those frantic, urgent times. Provoke only lasted three issues but its short life managed to revolutionize Japanese photography.

Still in 1968, Kamera Mainichi magazine began to introduce new trends under the korpora (contemporary) label. Young photographers were featured who shared a new approach to realism in photogrpahy based on a distinctly personal take on everyday life. Among them was Katsumi Watanabe who in “”Shinjuku Gangs” immortalized the Shinjuku underworld with his transgressive portraits of gang members, bar hostesses, and strippers.

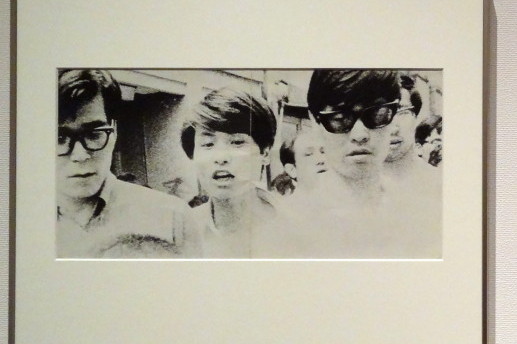

The student protests of the late ‘60s found their iconographic counterpart in the work of the members of the All Japan Students Photo Association, like Hitomi Watanabe who covered the “Tokyo University All-Campus Joint Struggle League.” In an effort to affirm the importance of the collective struggle, the students often published their works anonymously, thus questioning the idea of artistic authorship.

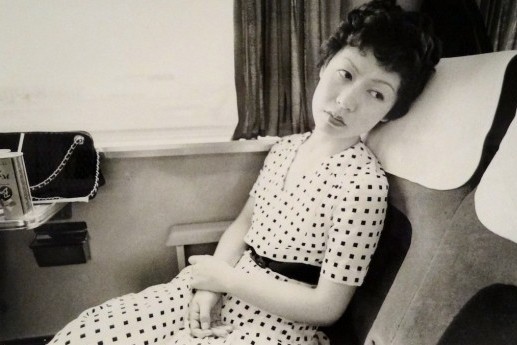

While some of the prime movers gradually distanced themselves from traditional photography and closed themselves in their private worlds (like Moriyama with his controversial “Bye Bye Photography” series from 1972), the seeds planted in 1968 gave rise to new personal ways to approach artistic creativity. One of the more noteworthy examples was Nobuyoshi Araki who, with the self-published “Sentimental Journey” (1971) championed a more personal, subjective approach to photography.

Randy Swank

Randy Swank