100 Years of Dada

It is a hundred years since the modern art avant-garde movement Dada first took Europe by storm. It has been almost a century since Marcel Duchamp first used the term readymade to describe his art objects, a century since Hugo Ball wore his ‘cubist costume’ to recite sound poetry, and a century since the nightclub Cabaret Voltaire first hosted Dada performances in Zürich, Switzerland.

In the Dada Manifesto of 1916, Hugo Ball wrote: Dada is a new tendency in art. One can tell this from the fact that until now nobody knew anything about it, and tomorrow everyone in Zurich will be talking about it. Dada comes from the dictionary. It is terribly simple. In French, it means “hobby horse.” In German, it means […] “Be seeing you sometime.” In Romanian: “Yes, indeed, you are right, that’s it. But of course, yes, definitely, right.” And so forth.

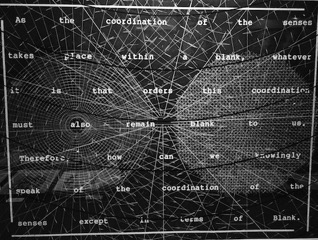

Formed as a protest against the barbarism of World War I, Dada embraced the absurdity of the modern world by making a deliberate departure from the rational. It was makeshift and reactionary, urgent and anarchic, daft and despairing. As a term, ‘Dada’ could be given to anything so long as reason was discarded first. Dada turned mass-produced objects into sculptures and assembled readymade imagery into anti-establishment collages. And unlike some of the European art movements that preceded it, Dada would not be constrained to a single creative field but spanned art, music, poetry, theatre, dance and politics.

The movement spread widely, finding resonance also amongst groups in Japan who saw Dada as a means of resisting established art authorities, whilst offering anarchistic modes of opposing the suppressive political powers of the nation. Tomoyoshi Murayama, a self-appointed interpreter of European modernism, formed the Dada-inspired group of art radicals “Mavo” during the 1920s. Decades later, in an atelier in Shinjuku during the early 1960s, Masanobu Yoshimura started the Neo-Dadaist group the Neo Dadaism Organizers. Alongside Ushio Shinohara, Shusaku Arakawa and Genpei Akasegawa, they too sought to jolt their audience with shocking protest performances.

The influence of Dada upon art in Japan can clearly not be neglected, and so the centennial of this anti-art, anti-authoritarian movement is naturally being celebrated in Tokyo. July saw the start of dADa100 Tokyo brought together by the likes of the Goethe Institut Tokyo, Institut français, and the Embassy of Switzerland in Japan. Events continue up to the end of September across multiple venues.

With so many events scattered across the city, the approaches that artists and organisers adopted to situate Dada in Tokyo today also varied. Arguably the most conservative, but no less captivating, way to celebrate Dada’s connection to Japanese art history is to recreate past performances. Re-staging a “Mavo” performance at Cabaret Voltaire at Super-Deluxe, a group of students from Kurashiki University of Science and the Arts wore geometric-shaped costumes that paid tribute to Hugo Ball’s ‘cubist costume’. Making purposeful movements with plastic hoops and positioning translucent screens, the performers concealed a hidden mirror in an event that resembled a modernist magic trick.

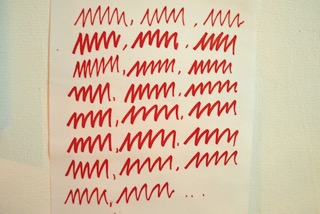

Another way that the “dADa100 Tokyo” program acknowledges Dada’s impact on today’s artists is by finding creators whose work could be seen to further the artistic experiments initiated a century ago. Along with Futurism, Dada was active in the development of noise music. For the finale of the ‘Indadadadustrial’ night at Cabaret Voltaire, the noise musician Merzbow (whose stage name is borrowed from the artwork “Merzbau” by the Dadaist Kurt Schwitters) collaborated with Eiko Ishibashi in an instrument-based performance that piled layer upon layer of distorted noise at a steadily increasing volume until culminating in a thunderous din.

But the clamour and the chaos of the original Cabaret Voltaire by the first Dadaists in Zurich isn’t easy to emulate. Nor is it a straightforward endeavour to create art in the style of artists from a different era to an audience aware of the previous generation. One of the reasons that the original Cabaret Voltaire made such an impression was the unpredictability of the acts. For all the challenges that working in traditions of other artists presents, there were some occasions in Tokyo when it felt as though performances were rehearsed rather than experimental.

There were other times during “dADa100 Tokyo” when artists wove traditions with current technologies to continue Dada’s irreverent customs. One such work was by the Swiss artist Nadja Solari, who exhibited a mixed media installation entitled ‘Nibble, nibble, gnaw’ at The Container in Daikanyama. Consisting of heart-shaped gingerbread biscuits decorated with spam email messages, the opening night included a performance that couldn’t be more Dada if it tried: wearing lederhosen and dirndl dresses, Japan’s Houkakai Yodel Club yodelled spam emails to celebrate Dada’s protests against senselessness. Here’s to the next hundred years.

Nick West

Nick West