Yurie Nagashima: And a Pinch of Irony with a Hint of Love

Yurie Nagashima was a university student when her nude family photo series ‘Self Portrait’ won the 1993 Urbanart Parco Prize and brought her fame. Her work radically depicting the lives and bodies of herself and those close to her has been championed and misunderstood ever since. On one hand, her nudes were viewed by some as nothing more than pornographic pubic hair-showing “hair nudes,” and the movement she led with other women photographers of her generation has been labeled dismissively as onnanoko shashin (“girl photos”).

However, Nagashima is also the recipient of the 2000 Kimura Ihei Award (Japan’s most prestigious photography prize), and in recent years her work is the subject of renewed focus as she frames it on her own terms, continuing to tackle themes of gender, family, taboo, and feminism with both boldness and subtlety. I spoke with Nagashima about the arc of her career at Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, where her exhibition “And a Pinch of Irony with a Hint of Love” is currently held.

The title of your exhibition is “And a Pinch of Irony with a Hint of Love.” Why start off this retrospective of your more than 25-year career midsentence?

It’s a shortened version of a recipe in English. Everyday things like cooking are a theme in work, so I started thinking, “What’s a good recipe for photography?” Mine is this: Curiosity, courage, and a pinch of irony with a hint of love. I don’t necessarily think about it when shooting, but when I go back and look at my work I see it there.

The show covers your career from when you first debuted through your recent projects, and it’s interesting to see how your work has evolved.

Yes. Some of the photographs, like the ones from the ‘empty white room’ series, had never been printed as museum-size images before.

What was it like to see those works in an exhibition? Did it change their meaning for you?

I found the prints quite beautiful – some of the colors were faded because the negatives had aged. The ‘Self Portrait’ slideshow I remade specifically for this show, but the project started in 2014 when I was asked to contribute to a film. I didn’t have experience with filmmaking, but I do think the slideshow works as a story of a woman’s life.

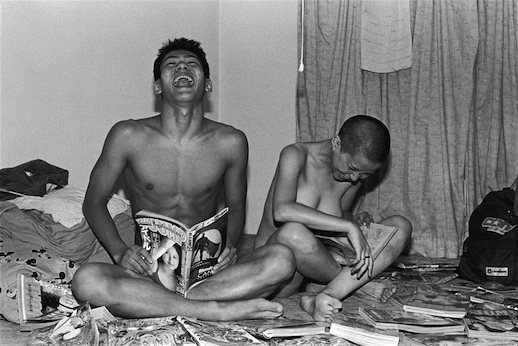

In your early work you photographed yourself and your family naked together, something not many would have the courage to do. Was it difficult to convince your family to go along with this?

No, it was rather easy. Maybe easier than it would have been in Europe or America – In Japan personal space is less sacred. Private rooms in homes weren’t common until recently, and when I was small, my grandmother would walk around topless after bathing. People apparently went undressed in public during the Edo period [17th–19th centuries]. Also, my parents were involved in theater when they were in high school, which maybe got them used to the idea of acting. Anyway, they were willing to play a role in my work, which was never about my family specifically, but about asking, “What is family?” My brother was a little shy about doing it though. (Laughs).

So you wanted to explore the idea of family, but how important was it to you to use your own family in your work?

Well, for one thing there were financial considerations – I didn’t have the money to hire models. I also didn’t want to have to ask other people to get involved. Even with friends, taking nude photographs of them would have brought another level of self-consciousness and stress. So I decided to do what I could myself. That’s how it all got started.

In graduate school there was a class where we analyzed our own works with each other. Currents of feminism were very strong there, and my self-portraits included some pretty provocative poses. One of the other students said my work promoted a “geisha fantasy,” but in Japan there’s no such thing. I realized my peers did not have the same cultural background and couldn’t understand my work in certain ways. Of course, there were many things I didn’t understand about their perspectives, and often our discussions didn’t mesh. This left a pretty big impression on me. If you don’t understand something from square one, it changes everything.

To make my work understood in Japan, I said as little about it as possible. There was this strange conceit that if you needed to explain your work, it wasn’t really art; the more explanation needed, the weaker the work. The most important thing I learned in American is that you have to explain yourself. You have to ask, “Why?” That’s the kind of thing that makes older men in Japan mad sometimes. They think you’re defying them…So I think most people ended up misunderstanding my work. Most men saw my portraits as an extension of the “hair nude” trend.

They didn’t see you were satirizing tropes of women’s representation?

Hardly. There were also feminists who didn’t accept my work as feminism. Some did, though. Nakako Hayashi, an editor for Shiseido’s Hanatsubaki Magazine, was knowledgeable about third-wave feminism and wrote about its subculture heroes like Kim Gordon and Karen Kilimnik. She continued to argue that works by me and peers like Hiromix were part of the Girl movement happening in Western culture at the time. The art critic Noi Sawaragi saw the social satire, if not the feminism. Many critics – especially men – had no real feminist perspective. Twenty or 30 years ago you didn’t see as many women in art and media as you do now.

Would you say the roots of your work are in feminism?

Yes, absolutely. In high school I read a lot of Simone de Beauvoir. I also went to an all-girls’ school, where there were more female teachers than the usual school, and they had power. We did the carpentry and everything for school festivals ourselves – we were largely freed from gender roles.

Your photography deals a lot with images of women, and challenges the social perceptions and restrictions placed on them. For you, is self-expression the most meaningful way to do this?

Do you mean through self-representation, or creating art?

Both.

I believe in creating as a way of addressing society. Photography is strong in this aspect – the concept’s been there since the early days of photojournalism. For me, though, the artistic side of photography is more influential. Like with Dadaism and its ability to make fun of the situation we are in – that’s interesting to me – creating new expressions that can have direct connections to social change.

I’m not sure if I knew the phrase “the personal is political” at age 20, but I certainly believed it and worked from the idea. For me, using my body and my family in my photography was completely natural. I was born into a very typical Japanese household. There was nothing about my family that really stood out, so I sensed I had much in common with the rest of society.

You thought most anyone could identify with your work?

Yes. Unlike somewhere like America where it might have been interpreted through all kinds of social lenses, matters like ethnicity didn’t come into play. Maybe aspects of class came through in my work, but it wasn’t really discussed.

In Memories of A Back, your collection of essays that won the 2010 Kodansha Essay Award, you write about how you admire the paintings of Andrew Wyeth. Your photography often captures similarly natural, psychologically complex moments. What guides your impulse to press the shutter in these situations?

With ‘empty white room,’ I always had my camera with me when I was going out with my friends. I’d take along a strobe light, too. I do photograph the moments I find really beautiful, but I don’t think this necessarily makes me a photographer. As I photographed my friends, I started wondering what it means to preserve something in a work of art. I tried to position myself on the edge of things, but still I found myself interrupting situations and conversations. There is no way subjects can act completely naturally during shoots, and I realized that taking photographs brings an element of the unordinary into any scene. That made me question the meaning of what I was shooting. The years went by and I held on to my camera. I moved to America and back. Then I had a child and didn’t have as much time, which changed my work.

In my newest series from 2015 on, I notice a very different approach from the one I had in ‘empty white room.’ I don’t necessarily dive straight in to shooting a subject I like. I don’t have the same boldness. I’m older and so are they, and my reflexes aren’t as quick. (Laughs). I pass more moments up, and my work has become about those decisions, about reflecting the moments I let go of. You ask what my motivation as a photographer is, and it’s really nothing more than desire. There’s inevitably a lag between seeing what I want to capture and being able to capture it now. But that becomes a work of art, too.

I’d like to ask you a bit more about gender roles and feminism. In your photobook “not six,” you describe your relationship with your then-husband as a game you learn to play with more strategy, but with less risk and enjoyment. How would you say the “rules of the game” differ for men and women, in life and art?

They’re really quite different, aren’t they? When I wrote about the kick the can game, I think I was trying to work through my true feelings for my partner. The turmoil of wanting to stay with him while things weren’t going well… The game was about finding some kind of enjoyment in it. I focused on the day-to-day things, like if he washed the dishes…But let’s talk more about feminism!

Photography really is a man’s world. No matter how many more women photographers enter the field, as long as the rules of the patriarchy are in place things will stay the same. I think I got my start by taking risks and making mistakes. Photographing myself naked, for instance. (Laughs).

Really? I’d say that turned out well for you.

It did, but at the time doing things like that, or shaving your head like I did, was not the way to get ahead as a woman in Japan.

Yet you did these things intentionally, right?

Yes. I was sending a message. There were people who told me I should spend money on clothes and my appearance. That I should make myself more “feminine” and get a man. But I wanted to fail these tests. I made the choice to break out of those constraints.

The phrase onnanoko shashin (“girl photos”) was used to describe your photography when it rose to prominence in the nineties, but it has been criticized as undermining the importance of your work. Do you feel you were misrepresented?

Of course! I thought it was a crazy way to describe what I was doing from the beginning. It was so stupid, I thought there was no way that interpretation would be accepted by the world at large. So I neglected it, went to America, and when I came back I found that onnanoko shashin was the label given to all women photographers in that era. It was horrifying. I’ve always wanted to do something about it, so I recently wrote a graduate school dissertation about the term.

Would you say the critics who mislabeled your work did so because they didn’t have an understanding of feminism?

I think so. They didn’t understand, or they didn’t care, so they reinterpreted it in a way that suited them.

When they wrote about your work that way, did they consult you about it?

Not at all.

I’ve pointed these things out in my essays, and I feel that recently there’s been more writing about it from my perspective. But in 2000, the year I won the Kimura Ihei Award and the debate onnanoko shashin was at its height, the three women who received the award were given a single prize, as if we all belonged in that category. Many people wanted to put our diverse works in the same box. There was Kotaro Iizawa, who had been using the term onnanoko shashin leading up to 2000.

On the other hand, Nakako Hayashi wrote about the international Girl movement in fashion magazines, introduced its artists to Japan, and gave interviews and lectures about its relationship to the work of young women photographers in Japan. She changed the phrase to the Anglicized “gaarii foto” (girly photo). As more women read and wrote about the work, the interpretation shifted away from the “hair nude” description used primarily by male critics. Still, “girly photo” was used only in a light, pop-culture sense and Iizawa’s definition prevails. Probably a lot of women thought the term onnanoko shashin was horrible. There’s been a backlash, and now more editors are choosing to use the term “girly photo.”

It’s not just a difference of Japanese and English, though. It matters who uses the phrase first, and how it’s interpreted. Maybe then the survival of “girly photo” is better. But in 2010, Kotaro Iizawa started up with onnanoko shashin again, trying to define the era and the work through his own lens. When I read what he wrote, I felt that something I’d done my best to leave in the past was being unearthed again. Fifteen years had gone by, but the narrative hadn’t progressed at all! I can’t accept the way he’s tried to rewrite it on his own terms.

So I decided to go back to school. I want younger photographers to know the power of the work by me and my peers, and how we interpreted it. I want them to understand – for their own work, too – we didn’t choose snapshot photography because of a lack of skills, or because we weren’t physically strong enough to handle larger camera equipment. It was because the portability of those cameras suited our work, and this explanation made perfect sense. I discussed things like this in my thesis.

Well, I’m inclined towards the Riot Grrrl movement. I spent time in Seattle, largely because I liked the music scene there. I was into Bikini Kill, L7, the grunge/punk rock girl band scene.

Do you see a connection between the music of that era and snapshot photography?

Yes, I’d say there’s something there…The idea that you can be a beginner and still create your own scene, your own movement. I think it has positive implications for feminism. The Riot Grrrl movement also really took off in the media before [its leaders] turned away from the spotlight. I think there are parallels between that and the girly photo movement in Japan.

What are your plans for the future? Will you continue to do collaborations and projects that focus on women’s lives and creativity?

Yes. I think the next thing I’ll do will involve my grandmother’s knitting.

An installation, maybe?

Probably. I don’t want to limit myself to photography.

What are your plans for writing?

I’m revising my master’s thesis about feminism and the reinterpretion of girly photos, which I plan to turn into a book. I’m aiming to complete it within the year.