Blossom Blast – A Feminist Spring

Japan is sadly a few years behind when it comes to empowering women, and the art scene all over the world has its own history of belittling or ignoring women artists. The painter Miki Saito, along with the creative consulting agency TokyoDex and and UltraSuperNew Gallery, saw the need to respond to this thorny issue, and for two years now they have been shining a spotlight on women artists with the Blossom Blast exhibition coinciding with International Women’s Day on March 8. Will it become an annual event for years to come? One can only hope so.

Blossom Blast 2016 featured Japanese women artists, but this year’s show is more international, presenting seven main artists as well as a rotating easel of other creators with work displayed in the gallery’s front window. About curating the event, Saito said she looked for up-and-coming artists whose work was appropriate to the theme “What it Means to be a Woman.”

The kick-off event featured an appearance by a member of the Tomorrow Girls Troop (TGT), who identified herself only as the late Showa-era actress Hideko Takemine and presented “Hidden Feminist” awards to Lean In Tokyo and the Blossom Blast team. TGT members call themselves fourth-wave feminists in a social art collective striving to achieve gender equality through pop culture in Japan and Korea. Their masks are an obvious nod to the Guerrilla Girls, the anonymous collective of feminist artist/activists formed in the mid-Eighties. The TGT awards ceremony was built up to be a performance with each act and object having its own significance, but the audience was left wondering when this show would actually begin. Takemine’s outfit had a green-and-yellow arrow on it, a shoshinsha mark indicating the wearer is a “beginner” of some kind. Could this symbolize that TGT is a group of fledgling feminists, or that the feminist movement in Japan is still in its infancy? The message was unclear.

Anna Sato’s performance on opening night was more successful. Hailing from Amami Oshima in Okinawa, Sato came to Tokyo at 18 to be a pop star, but has returned to her Okinawan roots. She explained that women from her island traditionally sang while men played the shamisen. The vocal style distinctive to the southern islands was developed by men who wanted to sound like the female singers. Although she is female, Sato played the shamisen or shijin drum throughout her vocal performance and gave an explanation that poignantly connected her performance to the show’s theme.

As for the visual art displays, the curators selected works with both artistic merit and commercial appeal to attract viewers and sponsors. Miki Saito switched from her trademark ink paintings to acrylic and painted a list of “red flags” for women artists. The fact that this excellent advice is written in English instead of Japanese makes one wonder what mishaps occurred in the past year as Saito’s star has risen on the international scene. Considering the location, it would have been nice to see a Japanese version as well. It was also exciting to see Calligrapher Mami not rest on her laurels from last year but continue to challenge herself with colour in the calligraphic piece Kunoichi (literally, “female ninja”), which forms the kanji character for “woman” and could also be regarded as abstract art. Rika Shimasaki surprisingly went in a different direction with resin sculptures instead of the decorative acrylic paintings with which she had been creating name for herself. Kuristina Culina continued to work with fibers, but does not regard herself as a textiles artist and chose the medium because it was at hand. Does she not realise that crochet and knitting are traditionally regarded as women’s work and that the choice is a statement in itself? Although what appeared to be a giant penis might seem like an odd choice in a show celebrating International Women’s Day, Culina explained that it was in fact a breast with the nipple stretched out to represent gender fluidity and how one person could reflect a different male:female ratio at any given moment. If Blossom Blast becomes an annual event, how might these four artists continue to express themselves in the future?

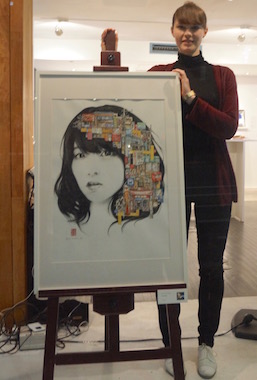

Blossom Blast newcomers are Hannah Van Ginkel, Sabrina Horak, and Kit Pancoast Nagamura. Horak’s acrylic-on-wood installation Fontana Eli Fontana (2015) exemplified the theme of women’s strength and was used on the promotional material for the show. In Vision (2016), Horak obviously used herself as a model but explained the work is not a self-portrait. She as an artist is the protagonist in her painting, like an actress is in a movie. She has used her body to make the poses she thought the painting needed. Van Ginkel’s collages created with what appeared to be pictures from magazines (perhaps reclaiming paint-by-number or found paintings) are intimate pieces that demand the viewer to lean in closer for a good look. Pancoast Nagamura’s pair of photographs All I’ve Done for You, I & II (2016) are taken of the same woman on the same day in the same hour, yet look like they are of two different women, or that perhaps one image is Photoshopped. The top photo shows all of the woman’s perceived flaws, including a flabby belly that many women get after childbirth and scars after breast surgery. The bottom photo presents a more typically idealised version of the same woman. As a pair, these images are meant to show how visions of oneself vary with different perspectives at any given moment. Pancoast Nagamura wants women to think about their bodies and the things that they do to them: Who is the real you? For what and whom do you make choices about surgery, cosmetics, or clothing? The dialogue between the photographs is interesting even without explanation, but a written statement – even a date stamp including the times of the images – could instigate conversation when the artist is absent.

Two of the rotating easel artists, Erica Ward and Natale Adgnot, came to opening night to show their support. Ward does detailed illustrations with pen and watercolour that seem to be fusions of East and West, the good and the bad, drawing attention to things that Japanese eyes might not usually see. On March 6 Adgnot, who is a textile designer turned painter, displayed Polymorphs (Aragonite and Calcite) (2016) from her ‘Mineral Siblings’ series inspired by the similarities and differences between human siblings and their counterparts in crystals formed by mineral twinning. The background of her painting is filled with the faces of famous people and their siblings such as Frida Kahlo and her sister. The faces of the celebrities are presented upside down, giving the lesser-known siblings their own moments to shine.

Blossom Blast 2017 is the team’s sophomore attempt, and their growth can be seen. They seem adept at balancing curatorial decisions with commercial ones. The lack of a full list of participating artists from the show’s outset was a problem, but the existence of such a large pool of talent demonstrates there is no shortage of willing and gifted artists for Blossom Blast. The team might want to consider other options for future shows, such as a larger space, additional venues, an extended exhibition period, or possibly a series of more live performances. Harajuku could be a prime location for just such a female-centric event, considering Harajuku Girls (not Harajuku Boys) have become a branding image in themselves. If Blossom Blast continues to focus on young female artists, why not a Harajuku Art Night to rival the ones in Roppongi and Ginza? Also, if age is not a factor, how about showcasing older artists who might never have received the acknowledgement their male counterparts have? Such a move could help younger artists in Japan learn about their own art heritage. More workshops on women artists and feminist issues are also needed to aid artists in transitioning from “beginners” to known and respected creators. The multilingual, international Blossom Blast team is surely up to the challenge.

Michelle Zacharias

Michelle Zacharias