Colour and Comfort by Chemistry

You want to get rid of things that get you into trouble.

Frank Stella, “Questions To Stella and Judd” interview by Bruce Glaser.

It begins in Sakura. The Kawamura Museum shuttle stops by Keisei Sakura, then Sakura Station. From there the journey is the same: past the convenience stores, garages, gas stations, company headquarters, industrial sites, and ramen shops. It takes about twenty minutes to the museum, which is tucked away amongst woodland.

DIC Corporation, an important Japanese chemical manufacturer, specializes in inks and dyes for commercial printing. It perhaps follows then that Katsumi Kawamura, president from 1958–1978, took an interest in painting. Through the firm he amassed a diverse collection of art focused particularly on the 20th century, and in 1990 built a museum designed by Ichiro Ebihara to house its treasures on the grounds of the DIC Central Research Laboratories. The site and collection have a rarefied and cleanly atmosphere – an achievement for a museum on the outskirts of Tokyo’s urban sprawl on the line to Narita Airport.

The current exhibition “Arbors of Art: Eleven Rooms Where Paintings Reside” showcases paintings from the collection. Displaying these works spanning centuries and continents all together could have the effect of flattening history and creating casual crosscurrents, yet the eleven spacious and distinct rooms are such that each section can be understood in isolation. As the title suggests, the show draws attention to the importance of the museum’s architecture and its capacity to support the artworks themselves.

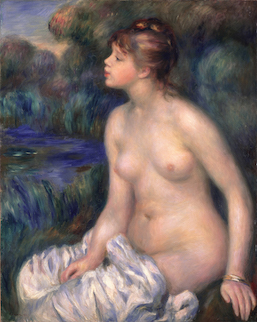

Most of the first floor (with the exception of the Japanese paintings of Room 110) explores early 20th century European Art, taking a figurative focus. Paintings by Renoir, Bonnard, Matisse, Braque and Picasso depict women bathing or at leisure, subject to the male gaze. The paintings hold a variety of psychological projections, ambiguities and pictorial concerns in their treatments of the female figure as motif. They are full of pattern, strange spaces and representational details.

The arrival of American painting in the latter rooms is where “Arbors of Art” comes into its own as an exhibition. An elongated heptagonal room on the first floor takes us across the Atlantic to Mark Rothko’s ‘Seagram Murals’. These paintings sit in soft light under security cameras amongst the purr of air conditioning. Leant gravity by their spacious setting, they are hung so each can be viewed alone and undisturbed: The room is truly an arbor for his paintings.

Rothko’s work requires sensitive treatment, and he understood this. These murals were originally commissioned in 1958 for the dining room at the Four Seasons restaurant in New York, but after working on them for about a year and a half, he became disillusioned with the corporate commission and the idea of the restaurant as a site for his work, ultimately rejecting the project.

The second floor gives further attention to American modernist painting. Room 200 is large and bright, both of its ends finishing with large curved windows through which dark green trees and the sky are visible. At each window stands a sculpture by David Smith and between these are a Jackson Pollock and an Ad Reinhardt: That is all. Reinhardt’s dark-on-dark painting has a similar feeling of density and weight to Smith’s sculpture, and its subtle color gradations mimic the effect of Smith’s black sculptures against the trees. In contrast, Pollock’s painting has great freshness with its rhythmic, lively marks and lighter palette. Again, the architecture provides the psychological space to engage seriously with these works. The trees at each window soften the light, while the spatial environment and cleanliness of the room allows for an undistracted viewing.

At the heart of the museum is a vast box-like room that hosts the works of Frank Stella, chronologically tracking his ideas of expanded painting. Hung together on one wall are Stella’s early paintings ‘Tomlinson Court Park (second version)’, ‘Marquis de Portago (second version)’ and ‘Tampa’. Dully colored, still and to-the-point, their painting-as-object status is produced by thick lines that mimic canvas shape and gradually diminish in scale towards a lonely central point or territory. Gone are European concerns of pictorial space and figuration with all their complications; Stella has worked them out of these early paintings, divesting them of any effects that might interfere with their object-hood. Exhibited solidly and center stage, their concentric patterns serve as a metaphor for the museum’s effort to create a resonant art space through architecture and environment.

‘Arbors of Art’ tracks the movement of painterly concerns from Europe to America, where ideas of pattern, flatness and painting-as-object are taken up and questioned, with overtly figurative images gradually disappearing. These American works are particularly well supported by the museum’s compartmentalization, minimalist architecture and use of light. They benefit most from the isolation, even depending on it. They stand distinct from each other in their separate rooms, in this museum, in a forest outside Sakura: Away from any trouble.

Calum Sutherland

Calum Sutherland