Yokohama Triennale: something borrowed, something new

As a part of this year’s Yokohama Triennale, one of the things curator Akiko Miki promises through the theme of “Our Magic Hour” is unexpected encounters. While the Triennale’s selection process does not aim for originality — many of the non-Japanese works have been shown before in biennales and art museums over the world — Miki is instead much more interested in creating a new encounter with the chosen works. The audience can find mixes of, for example, media art with craft, precious objects with trash, and Japanese artists with non-Japanese artists.

This review will focus on one other combination: the themed pairing of older art with contemporary works. Inside the Yokohama Museum of Art (YMA), the primary venue for this year’s event, this re-showing gave the opportunity to place contemporary artworks alongside older works from the museum’s collection to make an original context. This review will take three of YMA’s rooms for focus.

In the first room, three different artists interpret circles. Lyota Yagi is known for his vinyl record art. In a nod to John Cage’s prepared piano, Yagi makes prepared records, covered in various materials that will alter the sound when it is played on a turntable. In this room, the video ‘Portamento’ documents Yagi using the spinning record as a pottery wheel. One of his cassette tape-wrapped spheres, as seen earlier at this year’s “MOT Annual” exhibition, was on display as well. It sits atop a spinning tape head, omitting tiny, crackling sounds through the speakers.

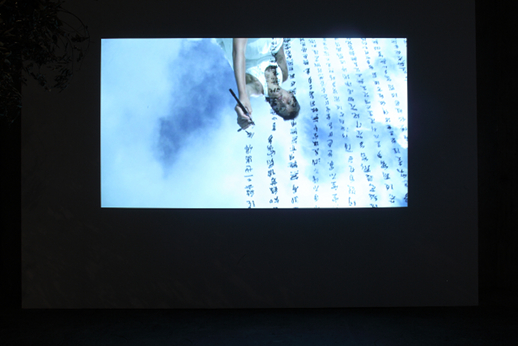

This room also features a signature piece from the YMA collection, Japanese-American artist Isamu Noguchi’s ‘Sun at Midnight’ from 1989. This sculpture is often discussed as a fusion of Western Modernism and Eastern aesthetics, much like the artist himself. In front of this piece, on a floating projection screen, is Taiwanese artist Charwei Tsai’s video ‘Circle’ from 2009, in which she draws a circle with calligraphic ink on ice.

The next room was introduced well before entering by the sounds of Massimo Bartolini‘s ‘Organi’; its sound floating throughout the atrium. Bartolini has used scaffolding pipes to construct a self-playing organ. The sounds are slow, simple notes, pumped out in an echoing space. Alongside Damien Hirst’s stained-glass windows (‘Tree of Knowledge’, ‘Samsara’), these works dominate the room and give it the feeling of a church. Consisting of thousands of butterfly wings on canvas, the Hirst exhibits give the impression of church windows at a distance. On second glance, the pieces also include patterns that resemble Buddhist mandala.

Hirst’s career-long interest in death and religion are perfectly expressed in this collage of God’s creations. Hirst is taking literal objects from nature and transforming them into something better than nature; the sublime. The room also contains ancient Coptic textiles, precursors to Western art as we know it now, giving a historical context to Hirst’s and Bartolini’s semi-religious creations.

Stepping out of the church room, the third space was devoted to photographs and other objects belonging to artist Hiroshi Sugimoto. His art practice is greatly inspired by ideas that transcend religion and — as the Triennale’s theme upholds — invests in the timeless wonders of the natural world. The artist has chosen to display some objects from his own collection alongside his art. His powerful ‘Lightning Fields 128’ (2009), an astoundingly detailed image of a thunderbolt, is hung in a small, oblong-shaped room alongside a Kamakura-era statue of Raijin, the god of thunder. In other small, adjacent rooms, a meteor measured to be as old as the planet or one of Sugimoto’s silver gelatine print seascapes, ‘Lake Superior’, can be admired.

Sugimoto is regarded as an artist whose interests spread equally to antiquity, science and architecture. By placing antique, even ancient, items from his collection alongside his artworks, the artist gives the audience a glimpse at the origins of his creativity. With his deep interest in all things timeless and sublime, this gesture in turn also gives a glimpse of the origins of life on Earth.

For more on the Yokohama Triennale 2011, see TABlog’s photo report on the two main venues.

Emily Wakeling

Emily Wakeling