Yoko Ono Talk: Tragedy, Art, and Peace

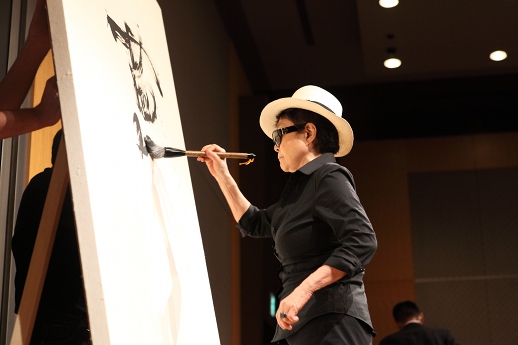

Yoko Ono is one of the world’s most famous Japanese people, primarily using her fame and money to promote art and peace. Her peace activism has recently been recognised through the Hiroshima Art Prize. Even at 78, she has a certain rock-star grace, no doubt shaped by her marriage to John Lennon. In trademark fedora hat and sunglasses, she addressed a full-capacity audience on August 4 at Mori Art Museum with a message for Japan in its post-quake state.

Leading up to this year’s anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb attacks, Ono talked about how the March 11 disasters give a new perspective to the nuclear tragedies of 1945. As an expatriate Japanese, she has observed dramatic changes in international reactions between 1945 and 2011. And as a young person in post-war America, Ono witnessed indifference and a general notion that Japan “had it coming”. However, this year, the artist saw people all over New York expressing sorrow and “praying for Japan”.

For Ono, the 1945 victims — the hibakusha — have become agents of peace. The cities’ remarkable recoveries, and Hiroshima’s efforts toward international nuclear disarmament have helped Japan to completely move on from the war. The victims have transcended their terrible fate and made something productive from their suffering. This is peace in action. Survivors of the Tohoku tsunami should look to the legacies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, according to the artist. During the long rebuilding stage ahead, she urges survivors to dispel fears and anger, and lead peaceful lives. Ono urges that this is the only way to transcend the tragedy and make it into something positive.

The question time, which took up the majority of the ninety-minute session, was almost like a performance art piece. People were invited to approach the microphone set close to the stage. A long line of audience members took this as a rare opportunity to interact with their hero. She obliged each person and offered answers on art, peace, love, action, national identity, fashion, and anything else she was asked about. At the end of the evening, a handful of people missed their chance to ask a question and went back to their chairs with tears in their eyes.

This spectacle reminded me of Ono’s most famous performance, ‘Cut Piece’, first performed in 1964 and performed in many locations throughout the world (including Japan). The artist takes a similarly passive role on stage, and invites audience members to come and cut pieces of her clothing off. Like the Q & A session, these performances are really about the audience and how they make a personal statement with their actions once it is their turn. No matter what they cut, no matter what the question, Ono is obliging.

As well as her solo show at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Ono’s telephone installation in the foyer of the Yokohama Museum of Art (as part of the Yokohama Triennale) can be thought of as an extension of the Q & A. If you happen to be near the phone when it rings, you can pick up the phone and talk to the lady herself.

Emily Wakeling

Emily Wakeling