Tokyo Grand Tea Ceremony 2010 (Tokyo Traditional Arts Program)

This is the ninth installment in a series of articles produced collaboratively by the Tokyo Culture Creation Project and Tokyo Art Beat. In this piece, Rie Yoshioka, editor of the Japanese edition of TABlog, reports on the Tokyo Grand Tea Ceremony, a one-day event that introduced visitors to the charms of the cha-no-yu Japanese tea ceremony last autumn.

Having heard in advance that the tea ceremony would be carried out in the extreme silence of a teahouse, I started to get a little nervous and wondered if I should read up on the finer points of the ceremony. How many times should I rotate the tea bowl clockwise after receiving it? What were the proper rules and etiquette that I should be aware of?

The attraction of the Tokyo Grand Tea Ceremony was that it allowed anyone to casually enjoy Japanese tea culture in an environment of cultural and historical significance. This year’s ceremony was again held at the Edo-Tokyo Open Air Architectural Museum and the Hama Rikyu Gardens. The former, located in Koganei City to the west of Tokyo, is an outdoor museum situated on the grounds of a park that houses historical buildings — a total of twenty-seven structures dating from the Edo period to the early Showa period that have been reconstructed and put on display, allowing visitors to leisurely enjoy the experience of having travelled back in time.

I participated in the session held at the Hama Rikyu Gardens, a classic example of an Edo period garden. Ocean water drawn from Tokyo Bay is diverted into the tidal pond, allowing the water to rise and fall according to the tide, which gives the gardens a constantly changing appearance. Although situated in the center of Tokyo, the gardens are a popular retreat from the bustle of the city where visitors can find a few quiet moments of reprieve. In the distance are the skyscrapers of Shiodome — a view that captures the sort of high-contrast urban landscapes typical of Tokyo.

Tea ceremonies were held at the teahouse on Nakajima, a small island floating on top of the tidal pond, as well as Hobaitei pavilion on the grounds of the gardens, while four nodate outdoor tea ceremonies took place at the Uchibori Hiroba open space.

In 1587, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the former Imperial Regent of Japan, held the Grand Tea Ceremony of Kitano at the Kitano Tenmangu Shrine in Kyoto for over eight hundred guests. Although he was a man of refined tastes, he invited everyone to participate in these ceremonies regardless of their social status, asking them to come with whatever utensils and implements they had to hand. Taking inspiration from this historical precedent, the Tokyo Grand Tea Ceremony was first held in 2008.

The art of the tea ceremony first became an established part of the education of cultivated women during the Meiji era. During the Sengoku period (1467-1573) in particular, when the art of cha-no-yu first came about, military commanders such as Hideyoshi and Oda Nobunaga became great patrons of the tea ceremony. Nobunaga apparently even started a war in order to get his hands on the famed Hiragumo tea kettle, one of the most valuable tea ceremony implements at the time. The owner of the kettle, Matsunaga Hisahide, refused to part with it, choosing to die a violent death and ordering that the kettle, too, be destroyed. Sen no Rikyu, another renowned figure in the history of the tea ceremony, was Nobunaga’s tea master. He stipulated that all weapons must be removed and left at the door of the teahouse — a space for secret trysts and mutual forgiveness where sins and grudges were forgotten.

The nodate outdoor tea ceremony, on the other hand, is a style that originated from the way in which military commanders took breaks to savor tea while enjoying the scenery and landscape on their expeditions. Compared to tea ceremonies held in a teahouse, nodate is a casual affair — almost like a picnic.

Among the crowd of guests on the day of the ceremony, there were also many young women dressed in distinctive white and black kimono, their hair all beautifully done up. As we were being shown towards our seats, the ceremony began to unfold on the small raised tatami-floored performance area.

The first guest to be led towards the ceremony from the waiting area was assigned the seat of honor. Each guest would then receive the tea in bowls that had been specially chosen by the host of the ceremony.

All the guests peered enviously at the tea bowls. Ceremonies conducted in the silence of a teahouse, however, demand a certain sensitivity on the part of its participants that will allow them to pick up on the particular tastes and preferences of the host. We were told that one’s knowledge of the tea ceremony, which governs how interactions with the host will unfold, also determines the vibe and atmosphere of the event. The air became fraught with tension.

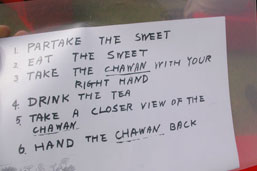

Tea was then served to each guest in turn. When the tea bowl is brought over, you bow once and express thanks to your host, after which you receive the bowl with your right hand and place it in the palm of your left. Next, you use your right hand to turn the tea bowl towards the front, making sure that the “front” of the bowl — the painted side – faces away from you (this custom varies according to the school of tea ceremony, however). After drinking the tea, the bowl is rotated again in the opposite direction so that the front of the bowl faces towards you. A formal tea ceremony also involves other verbal exchanges between host and guest centered on phrases such as “Would you care for another helping?”, or “Please excuse me for receiving this tea before you.”

At the outdoor tea ceremony for foreigners, tea was served to the guests while a running commentary and explanation was given in English, beginning with the philosophy and precepts that govern the spirit of the tea ceremony.

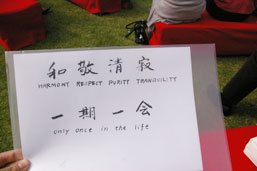

Wa-kei-sei-jaku is a set of four principles that expresses the spirit of the wabi-cha style of tea ceremony perfected by Sen no Rikyu.

Wa (Harmony): placing importance on the act of living together with others in the spirit of cooperation

Kei (Respect): paying respect and honoring one’s seniors, guests and other esteemed individuals

Sei (Purity): living with a chaste, untainted frame of mind

Jaku (Tranquility): living quietly and gently

Yukyu Akatsuka, who had come along to help out with today’s tea ceremony, is also involved in Kyutoryu, a School which performs tea ceremonies in office kitchens. This school proposes turning office kitchens into the sort of small, humble teahouses that Sen no Rikyu used to make, so that office workers can enjoy a tea ceremony while kneeling right there on the floor of these spaces. I asked her how we should interpret Sen no Rikyu’s philosophy of tea for a modern age.

“Sen no Rikyu said that we should leave everything behind at the door just before we enter the teahouse. In other words, discard all the preconceived notions that your mind has devised, and always take on new challenges with a fresh approach. I think Rikyu’s advice is actually just simple common sense. Human pride, vanity, knowledge and concepts get in the way, though – people tend to put on airs and take excessive precautions. What he’s saying, I think, is that we can start to get to the heart of things by getting rid of all of this baggage.”

It seems like all this somehow boils down to our own habitual actions and behavior.

Ichigo-ichie (once-in-a-lifetime) is another phrase that is often used in association with the tea ceremony. It refers not just to a simple encounter between people, however, but rather to a state of mind that prompts one to think about how to cherish the present moment. In this context, it refers to the necessity of honoring and paying respect to the host of the ceremony, just as if this was an once-in-a-lifetime meeting.

Visitors crossed the Otsutai bridge and made their way to the world of tea ceremony that awaited them on the little island floating on top of the Shioiri-no-ike pond. Proper teahouses are standalone structures in the middle of a small garden called a roji. By passing through the roji garden and entering the teahouse, you cut yourself off from the domain of everyday life in order to immerse yourself in the world of the tea ceremony.

Here, tea was served to guests in the silent atmosphere of the teahouse (by advance reservation). After tea was served to each guest in turn and the ceremony approached its end, the guest of honor led everyone in a conversation with the host about the calligraphy and flowers that adorned the tokonoma alcove.

During the tea ceremony, special efforts are made to create a uniquely Japanese idea of beauty based on imperfection and deficiency: an aesthetic ideal that can be seen in other artforms like renga poetry. At this particular session, the hanging scroll that graced the alcove contained lines of poetry about the towering peak of a mountain and the waterfront that stretched out all around it, reminding guests of the scenery and landscape outside the teahouse. The eggplant-shaped incense burner and ikebana floral arrangements in the alcove also created the impression of autumn. As we listened to the host’s anecdotes, the many sounds coming from the edge of the pond as well as the sound of distant birdsong, the inside of the teahouse fell quiet.

Both wa-kei-sei-jaku and ichigo-ichie are phrases that are relevant to everyday life. What are some other ideas and concepts from the tea ceremony that can we apply to our own daily routines?

“The chance to come into contact with well-made objects during the tea ceremony feeds back into your own creative activities as a designer, so to speak,” says Akatsuka.

“Take those mass-produced plates and cups that sell for ¥100, for example. Once you get tired of them you throw them away, thinking that you can just buy new ones — this is the sort of disposable lifestyle that many of us now lead. But there should also be things in our lives that we want to hold onto forever, well-made items that you want to use and cherish. The tea ceremony encourages us to question the cultural norms and background that we’ve been born and raised with, and to feel a profound sense of emotional attachment to the things that surround us.”

The implements for the tea ceremony contained in an old box made of paulownia wood included many items that had been handed down from one person to another, and the names of the previous owners of these objects were also inscribed on the box. The Japanese tea ceremony teaches us how to handle things that we would otherwise never come across in daily life, as well as objects that cannot just be bought and replaced using money. Yukyu Akatsuka tells us that she has been devoting her weekends to formal study and training with a tea master. This has allowed her to learn not just the proper etiquette, but also given her the valuable opportunity to become more acquainted with mingei folk crafts and Japanese history.

It’s embarrassing when you make a mistake during the tea ceremony — will the host get angry? These are the sorts of things that the beginner worries about. The act of rotating the tea bowl before drinking the tea is a gesture of courtesy: taking care to keep the front of the tea bowl clean and spotless so that everyone else can enjoy the sight of the painted motif. Part of the enjoyment of the ceremony also lies in being the recipient of the host’s kind hospitality, as well as the conversation that unfolds during the event. How to hold the bamboo tea spoon, how to handle the small cloth for wiping tea utensils, the correct way of walking on the tatami mats — for the novice, even just one of these points seems incredibly complicated and headache-inducing. These gestures, however, are all designed to allow guests to savor the tea and enjoy this “once-in-a-lifetime” encounter without any hitches.

There are many ways of enjoying the tea ceremony — art fans can find much of interest in the ceramics, calligraphy, crafts and flowers that adorn the tokonoma alcove. The opportunity to put on a kimono, too, is undoubtedly one of the attractions of this event. The tea ceremony offers its participants numerous ways of getting acquainted with its many charms. Where shall we start?

TABlog writer Rie Yoshioka

After working as an assistant to an art producer, she started working as a freelance exhibition organizer, editor and writer mainly for web-based publications. Has been organizing the Gallery Box series of exhibitions at Yokohama Bay Quarter since 2010. Other articles (Japanese)

Tokyo Culture Creation Project

Tokyo Culture Creation Project