Power in Numbers

As has been mentioned on this blog before, Tokyo’s art galleries are somewhat scattered. Of late, more and more of the smaller galleries have been joining forces and concentrating themselves in certain areas, such as Bakurocho and Kiyosumi-Shirakawa.

Now it’s Roppongi’s turn, where a large chunk of the art scene’s big guns are already situated: the Mori Art Museum, 21 21 Design Sight, the National Art Center, and the Suntory Museum. In contrast to the rather ugly nocturnal face of the ‘Pong (a pejorative moniker for the area), these impressive buildings draw large crowds, who are no doubt as grateful for their vicinity to each other as they are for their individual contents.

It was therefore refreshing to hear that Ota Fine Arts (previously in Kachidoki), Zen Foto (Shibuya), Wako Works of Art (Nishi-Shinjuku) and a third branch of the Taka Ishii Gallery were all moving into the Piramide building, close to Roppongi Hills. Opening nights are pleasant enough in themselves, what with the free flowing wine and animated conversations, but this one was a particular pleasure, thanks to the channel of people that trickled around each white room, forgetting which gallery they had accidentally stolen their wine glass from. The building itself emanates a cosy feeling of community, with Zen Foto and Taka Ishii on the second floor looking across the courtyard (complete with illuminated pyramid) to the other two on the third floor. The rest of the building is filled with shops, which will hopefully prompt viewers to remember that art is a commercial enterprise and cannot be sustained by praise alone.

Zen Foto, whose new space is not too dissimilar from their old one, was as bustling and welcoming as ever, with patrons juggling quesadillas, drinks and books from previous exhibitions. It’s run by the ebullient Mark Pearson, an English Sinophile who is doing his best to bridge the gap between Chinese and Japanese artists, via his other gallery in Beijing. It’s a valiant and commendable task, considering that the vibrant art scene in China often gets short shrift in Japan, and it’s likely that the four Chinese photographers whose work is welcoming the gallery to its new location are as-yet unknown over here.

While diverse, the quartet shy away from depicting the shiny, urban veneer of China that is currently garnering so much attention. Instead, they point their wistful lenses towards Tibet, other rural areas, or local people. The most striking are Liu Zheng’s “The Chinese,” which includes a portrait of a wonderfully wizened old man with shockingly bright eyes and big teeth.

Taka Ishii’s new gallery plays it safe, meanwhile, with a collection of vintage Nobuyoshi Araki photographs, some so old they bear watermarks and sepia tones. I never tire of Araki. Other artists get rather boring in their old age — take Hockney, or even musicians like Sting — as they tend to repetitively retread their steps or else desperately try to reinvent themselves to keep up with the kids. But Araki, perhaps because his subject matter has always been so diverse, seems untrammelled by the passage of time.

It occurs to me that if a Western photographer took such bluntly sexual and often violent photographs as Araki does, the rest of their work, no matter how varied, would most likely be tainted by association. In today’s hysterical moral environment, it is unlikely many people can take photographs of women in bondage on one day, and school boys in shorts on another without raising suspicions about their intentions for the latter, but Araki is fortunate enough to have evaded such narrow-minded categorisation. He runs the full gamut of genres, from soft porn, portraiture, landscapes, documentary and abstraction. Mirroring the lack of absolutes in Japanese morality, he sees no boundary between sex and the rest of life, nor his own private relationships and the streets and urban scenery that he photographs. The title of the exhibition, “Theater of Love”, is appropriate: the world is his stage, and he seems to adore everything in it.

Across in Ota Fine Arts there is also a group showcase of several different artists from different parts of Asia. The gallery is perhaps the largest of the four, with an exclusive room at the back concealed behind a green Perspex door. In the centre of the main room lies the attention grabbing ‘Translated Vase’ by Yee Sookyung, a large bulbous object made of broken pottery shards glued together with gold adhesive. It looks like a failed attempt by a maid to desperately stick back together the family heirloom she’s tripped over, but the way in which she subverts the traditional connotations of ceramics — as delicate and impeccable symbols of wealth — into something wonkily modern, is curiously attractive.

Manami Koike’s ‘Sanmai Kishou’, a painting of a geisha and three men with traditional hairstyles, is equally eye-catching. Its overall effect is unnerving, as it flirts with contradictions: it looks like a photograph, but it’s a painting; all the men have the same feminine face, creating a “tripleganger” effect; and like a biblical painting, it seems to allude to a larger and more complex story that it cannot fully explain. The men’s expressions are comical, a touch at odds with the seriousness of the painting style. A look at Koike’s other works shows that this is a common theme, as well as hilarious titles: ‘“This rice cake looks delicious. Can I have this?” “Don’t you dare. It could be horse dung.”’ The conflation of traditional scenes and modern humour is cleverly handled with a painting technique that is realistic, but slightly blurred, like a soft-focus photograph.

The master of this precise-but-blurry technique is perhaps Gerhard Richter, who is featured over at Wako Works of Art, along with a stellar cast of other high profile artists, including Luc Tuymans and Wolfgang Tillmans. The latter has recently excelled in the kind of abstraction to leave modern arts sceptics either cold or incensed at the disconnect between effort expended and the price demanded. In a move away from his frank and sharp snapshot style, Tillmans has more recently experimented with using photographic paper to produce intensely coloured squares, which he then bends, folds or crumples. Four of these are on display, along with a massive photograph of the corner of a photocopier. If you are aware of Tillmans’s background, this seems a little less obtuse: he began his career by tearing out pieces of newspaper and blowing them up by 400%, often documenting the rave scene that he was involved in at the time. I suppose photocopiers could be for Tillmans what fat and felt were to Joseph Beuys — a personal talisman to which he owes his career — but I’m afraid I don’t feel the former is as interesting as the latter.

Gerhard Richter’s “ALADIN” series is more successful. Looking very similar to the oil and water drawings many children try in primary school (swirl coloured oil in a bucket of water, drop paper on the surface, repeat) but much more intensely coloured and the pattern more consciously composed than arbitrary. Viewed in February, the canary yellows and vermilions are a happy reminder of warmer, perhaps Californian climes.

So bright are they, in fact, that they rather overshadow Luc Tuyman’s characteristically faint painting, ‘S. Croce II,’ a Greek bust painted in bluish grey. Fiona Tan’s ‘Cloudy Study 1’ is also monochrome, with the aerial shot of thick and puffy clouds bringing to mind both traditional Chinese wall hangings, and the atomic bomb aftermath.

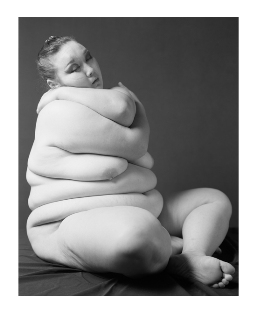

In the room behind is a bizarre trilogy of photographs entitled ‘Mehlorgie’, (“Flour orgy” in German) by Gregor Schneider. In them the artist contorts himself, covered in what looks like porridge or some kind of industrial sealant — probably not a look I’ll be recreating at home any time soon.

Wako’s star cast hits a few weak notes for me, perhaps because I’m not really in the mood for such abstractions and/or wheat-based orgies. Yet as a peacock-esque display of their cache and might in the art world, the names alone are impressive, and the crowd was both numerous and seemingly appreciative. I’m excited to think about not only the next exhibitions that these galleries come up with, but the fact that I can now kill four birds in one fell swoop.

Sophie Knight

Sophie Knight