Festival/Tokyo 10 – a performing arts festival</br>Norimizu Ameya “The Shape of Me”

This is the eighth installment in a series of articles produced collaboratively by the Tokyo Culture Creation Project and Tokyo Art Beat. In this piece, TABlog writer Rei Kagami gives an introduction to the performing arts festival Festival/Tokyo.

Festival/Tokyo (F/T) has been held three times so far — the first edition kicked off in the spring of 2009, followed by a second installment in autumn the same year. Last fall, F/T unveiled its third edition in October and November 2010. Despite the name, this “festival” is not a series of presentations of finished work held over a fixed period of time. Rather, F/T’s basic objective is to become a platform for creation and artistic production: the organizers themselves are actively involved in producing work together with the artists. Around one-third of the festival program consists of performances that F/T has produced independently or in collaboration with other artists — a fact that distinguishes F/T from other similar performing arts events.

F/T’s two previous installments featured 39 works, 282 performances and a total of 1,392 performers and staff members. Visitor numbers stood at around 120,000, making this an extremely large-scale event.

Although F/T is a new festival that has just gotten started, it is hard to believe that a comprehensive performing arts festival like this one did not previously exist in Japan, a country with its own diverse theatre culture. In the context of this situation, F/T promises to be a massive boon for the overall development of the performing arts in Japan.

For most people, the first thing that comes to mind when the phrase “performing arts” is mentioned is probably theatre. At a time when the number of entertainment options — high-speed Internet, online gaming and home theatres — available to us without even leaving our homes has grown, the medium of theatre has also evolved with the times to become more complex. The variety of its formats has diversified and its engagement has deepened. Theatre can no longer be confined to the image of a “play” with a script, performed on a stage in front of a seated audience. F/T is a frontline witness to these cutting-edge developments in the performing arts world.

The theme for the third installment of F/T was “disrobing theatre”.

This was a call to action that prompted participants to open up new possibilities for the performing arts by doing away with the entire framework of “theatre” — script, playhouse, stage, actors.

There were two approaches to this. One was to break away from the narrative element of theatre. The other was to get away from the space of the auditorium itself and charge the audience members, rather than the actors, with the task of leading the production.

But just what exactly would theatre without a story look like? A performance where the amateur audience members take the leading roles — what would that be like?

One of the greatest attractions of theatre is its one-off nature. Even with productions that are based on the same script, small differences emerge out of each performance: it is impossible to recreate the exact same performance each time. The act of watching a recording of that performance seldom conveys the vibe and atmosphere of actually being present in the audience. In short, theatre is a singular, one-off event that can only be experienced in the first person: the unfortunate thing about it is that no matter how you try to explain it using text or photography, you can never reach a proper understanding if you lack firsthand experience.

In this piece, I hope to convey at least something of the significance of this approach through a review of Norimizu Ameya’s “The Shape of Me”.

Those who attended Ameya’s performance were given only the following information in advance: that it was a piece based on the theme of “real estate”; an “experience” with no stage, actors or play to speak of. Advance reservations were required, and only one person could view it at a time.

Viewers who turned up at the reception on the day of the performance were handed a single sheet of paper with a set of instructions on it and told to make their way, alone, to a series of four checkpoints. Each sheet of paper only contained directions leading to one of those places. After seeing the performance there, viewers would receive a map showing them how to get to the next venue.

The first stop was a huge gaping hole that had been bored into the ground of an old school courtyard. The following text had been pasted near the hole:

Hey, master

Let’s say I tried to live like you, even just a little

I’d be a sinner for sure

I’d be terrified of that

I’m terrified of listening to the wisdom of humans

This hole, while evoking the earth to which we all return after death, is also a metaphor for “falling into” sin. The entire work functions on a symbolic level, but the unnerving scale and religious tone of the text also stirs up the anxiety of the viewer who has just started on his or her journey.

The three other venues that followed this first one were all abandoned, ruined houses — metaphorical “holes” — in the quiet residential district of Sugamo.

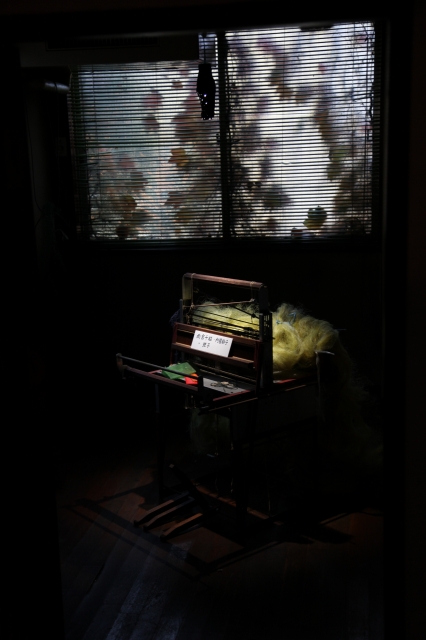

The second stop was an old Japanese single-storeyed house where a concubine used to live — or so the rumor goes. Although it was all run-down and dilapidated, signs of human life had been carefully put in place: charcoal burning in an earthen brazier, a bathroom damp with moisture. The whole scene had been set up to prompt audiences to imagine what the (alleged) former resident was like, and the life she used to lead here. Here, too, texts resembling passages from the Bible had been pasted on the walls, making visitors keenly aware of the carnal sins and other associations conjured up by the word “concubine”.

Led by Goto, an ardent believer of the Christian faith, Kibosha was a philanthropic organization that carried out relief missions to help sufferers of leprosy and other marginalized members of society. In the end, however, Goto’s reputation was utterly destroyed by a scandal that erupted over his involvement with a young girl. Here, too, the Christian injunctions on the walls evoke the sins and pitfalls associated with worldly desires.

While some parts of the building recreated the vestigial traces of a former life (or so it seems) in chilling detail — a half-open dresser and wardrobe, bits of half-used soap in the bathroom — the beehives and dried flower installations in some of the rooms also created moments of heart-stopping beauty.

With no more life in them, however, both the empty husk of the beehive and the bunches of dried flowers alluded only to death.

The fourth and final venue was a former hospital. Perhaps this pile of earth mixed with bits of grass, piled up in a dark room, used to be part of that hole in the ground? The beautiful arrangements of dried flowers and stacks of clothes lying on the floor remind us that the people who used to put them on are no longer here, evoking images of their passing.

Climbing up to the second floor, you arrive at the only room in the whole building where photography is not allowed. Human bones lined up in neat rows on stretchers forced visitors to directly confront images of death.

The journey ended at this building, but visitors leaving the hospital were handed a piece of paper with the following words written on them.

I was born in Japan.

I have no religion;

I am an atheist.

Having viewed all the “performances” and returned to the ordinary rhythms of everyday life, audiences confronted with these words found themselves thrown into the depths of the hole they had just seen. Or perhaps they discovered a gaping hole that had just opened up in their hearts.

Viewers who found their imaginations piqued by the lives of those who (apparently) used to live in the abandoned houses they visited “saw” these people in their minds, even though their physical substance was absent. In addition, the former hospital at the fourth stop aroused a certain anxiety and uneasiness about their own impending future absence and death. When the audience is finally discharged back into the realm of everyday life along with the piece of paper handed to them, they realize that the sins committed by the actors whose presence was only alluded to by various signs and traces, as well as the protagonist of the “hole” that absorbs its own sins, are in fact lying empty within their own minds.

The so-called “invisible” actors in “The Shape of Me” produced a variety of different impressions in the minds of each audience member — impressions that could not have been identical to each other. If the act of being a spectator at a traditional theatre performance is a passive experience of enjoying a story made up of visual elements, spoken lines and other sounds while seated, Ameya’s production, in comparison, made overwhelming demands on his viewers: that they invest the performance with their own individual interpretations and personal emotions.

Traditional styles of theatre-going allowed viewers to partake of an experience without letting them share the experience of either the actors or other audience members. This phenomenon was encapsulated by the sense of loss represented by the hole at the first venue, as well as an excellent case in point for understanding this whole experiment in “disrobing theatre”.

As mentioned above, one of the real charms of theatre and the performing arts is their sense of real-time presence. Although it is an unfortunate fact that what makes these art forms truly valuable will never be able to leave the realm of the imagination as long as they are not experienced firsthand, videos and photographs that document extracts of each performance have been made available for viewing on the official F/T website.

In addition, the next installment of F/T is slated to be held from September through November this year. The tentative theme, referencing the title of a work by playwright Shuji Terayama, is “Get Rid of the Theatre, Rally in the Streets!” — hinting at the provocative productions that we can expect.

Rei Kagami, TABlog writer

Born in 1975. Lives in Tokyo. After graduating from university, she worked full time while completing a correspondence course at Musashino Art University to qualify as a curator. After helping to organize some exhibitions as an assistant curator and working as an exhibition tour guide, she started full-time work in the art industry in 2005. Other articles (Japanese)

Tokyo Culture Creation Project

Tokyo Culture Creation Project