Gravitational Modes of Viewing

In the quietly gesticulating art scene nestled among the winding streets of Tokyo’s Yanaka district, a series of Lee Ufan’s meditative paintings have come this month to reside on the welcoming walls of SCAI The Bathhouse.

Having recently received his own museum on Naoshima, and a solo show at the Guggenheim NYC approaching this summer, one can safely say that Lee Ufan’s time has arrived. Leaving school in Korea, Lee moved to Japan in 1956 to study at Nihon University, graduating from the department of philosophy in 1961. He is the most vocal and well-known artist of the Mono-ha (School of Things) movement originating in the Sixties when Lee drafted the group’s manifesto, expounding a theory of minimalist expression and relationality that he continues to perfect today.

As with most minimalist modern art, Lee’s work is best viewed with time and silence. Part of the great acclaim showered on his Naoshima museum is the result of collaborative planning between Lee and architect Tadao Ando to create rooms optimized to facilitate what I call a ‘gravitational’ mode of viewing, with paintings applied directly to the walls and stones embedded in the floors to avoid disrupting the totality of environment.

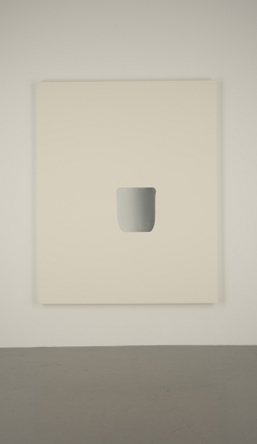

Most of Lee’s work can be divided into sculpture or painting, with similar concepts flowing through both. For sculpture, immovable stones and sheets of swarthy steel lean against a wall to create their own gravitational presence, while Lee’s painted works tend to be swaths of sandy textured painted waves, color gradation residing solitarily on large white backgrounds. Works from both styles imbue the exhibition space with a deep sense of their presence, like the pull of heavenly bodies against each other. The physiological density of rock, wood, pigment, and metal attract tendrils of light, nebulae of space, and the satellite of the viewer’s gaze in orbit around the work, binding the whole room together.

The works at SCAI for this show are all canvases with ‘waves,’ sweeping gritty paint made from stone pigments, meticulously brushed linearly to form a monochrome ebb and crest. These works convey Lee’s meditation on material, on form: the straightness of a line, the precision of technique. One does get the sense that Lee could keep making these waves indefinitely, and that viewing such works is more about viewing periods of his creative meditation than autonomous statements. At SCAI the viewer must bridge the off-white canvas and white walls of the gallery to achieve the sense of continuity between the presence of the wave and space of surrounding room. Lee said that ideally there should only be one ‘wave’ alone in a whole room to achieve the proper ratio or relationship to the overall space.

While the generally held description of Mono-ha emphasizes the relationship between things, Lee pointed out that this is a common misconception in both Japan and abroad. Mono-ha is “not just a close-up on Things,” he says. Rather, “we tried to draw out those things that didn’t have an affixed image, things produced by an industrial society, steel or glass, things in as natural a state as possible like stones or water. Basically things to which images or ideology cannot be affixed.”

While the generally held description of Mono-ha emphasizes the relationship between things, Lee pointed out that this is a common misconception in both Japan and abroad. Mono-ha is “not just a close-up on Things,” he says. Rather, “we tried to draw out those things that didn’t have an affixed image, things produced by an industrial society, steel or glass, things in as natural a state as possible like stones or water. Basically things to which images or ideology cannot be affixed.”

This is a gesture against the cognitive trap of labeling, of ‘making sense’ through transfiguration or the preemptive act of interpretation by the viewer and artist. About the direction of Mono-ha and his own work, Lee states: “We couldn’t go on thinking in the same ways as before, we tried to draw out something that couldn’t be put into words, things you couldn’t articulate….By placing things made by industrial society or by nature in galleries and museums we asked: What can we see? How do we see?”

By collapsing the categories of natural vs. industrial production in favor of base principals, Mono-ha was able to forward a new ontological position through seeking a precognitive aesthetic, works that came before words and ideology. Arguably, this was an attempt to short-circuit the continuous yet eternally incomplete act of labeling and interpretation — a fundamental way of being for contemporary society — by excluding or preconditioning the ability of discussion and contemplation itself. While this leaves Lee open to a materialist critique (Is there no difference between nature and industrial society?), he would likely argue that I’m falling into the exact trap he tries to avoid.

Previous TABlog editor Ashley Rawlings wrote an introduction to Mono-ha in 2007.

Kenneth Masaki Shima

Kenneth Masaki Shima