The forests where time stops

Ancient lore in India tells a story of the great emperor Asoka who once made an order in his kingdom to plant five trees, calling them the “five small forests.” These trees were to serve five different purposes: one to cure diseases, one for fruits, one for flowers, one for firewood and one for housing supplies. Basing “Forests of Asoka” exhibition at the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art on this lore, Jae-Eun Choi created her own version of the forests to reflect and explore the idea of the eternal coexistence between humans and trees.

Choi’s interest in trees may have risen from her first visit in Japan in 1976 where she started to learn about ikebana, the traditional art of flower arrangement. She became a student, and later an assistant from 1984 to 1987 to Hiroshi Teshigahara, the third generation master of the Sogetsu school of ikebana. “Forest of Asoka” is Choi’s interpretation of ancient lore while incorporating her background in ikebana’s philosophy. The result is a collection of works with overwhelming atmospheric serenity that aims to encourage affinity with nature.

The large-scale installation ‘Forest of Asoka’ has two different levels, arising from an upward inclining floor built up with rectangular wood logs, leading us towards a window with a view of the museum’s garden. The installation gives a sense of a path that leads us into somewhere of the in-between gap of time: a meeting point between reality and the eternal realm of immortality. Contrastingly, the impact of the installation from the upper level’s view changes tremendously and acts as a sharp pull back into reality from the previous dreamlike state we sensed below. The multiple views of the installation contributes to Choi’s commentary on how humans seem to neglect nature even though we have always coexisted, and that by changing our perspective only a little, we can see the spiritual connection of that very coexistence again.

The large-scale installation ‘Forest of Asoka’ has two different levels, arising from an upward inclining floor built up with rectangular wood logs, leading us towards a window with a view of the museum’s garden. The installation gives a sense of a path that leads us into somewhere of the in-between gap of time: a meeting point between reality and the eternal realm of immortality. Contrastingly, the impact of the installation from the upper level’s view changes tremendously and acts as a sharp pull back into reality from the previous dreamlike state we sensed below. The multiple views of the installation contributes to Choi’s commentary on how humans seem to neglect nature even though we have always coexisted, and that by changing our perspective only a little, we can see the spiritual connection of that very coexistence again.

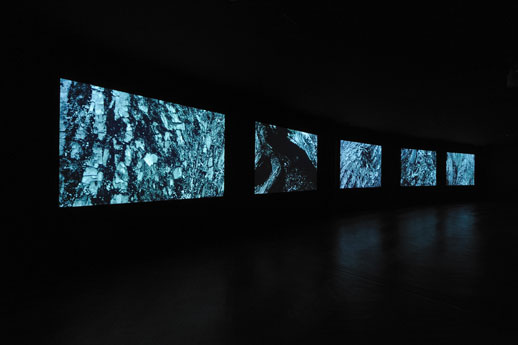

‘Forever and a Day’ is a collection of five video screens where the shots pan around slowly, zooming in on different parts of trees. The panning is at such a slow speed it is difficult to notice they are moving images at first glance. The speed of the camera seemingly reflects the image of trees as something close to immortality. Connected to ‘Forever and a Day’ is an easy-to-miss entrance to the next exhibiting space, ‘Another Moon’, a smaller scale installation of a video projection on “antique stone laver”. From afar, the piece resembles the moon, but upon closer inspection, the image of a tree slowly rotating becomes visible. The whole piece gives out a mythical atmosphere while at the same time exploring Choi’s concept of trees as the basic source of serenity in life.

The exhibition on the second floor rather contrasts with the emphasis on nature’s serenity and immortality on the first floor. ‘Since when has the forest been there?’ and the two galleries of ‘The Other side of Illusion’ seemingly focus more on the dichotomy of our fast-paced lives with images of stillness and timelessness in trees. The video installation ‘Since when has the forest been there?’ is in a room with an extremely narrow entrance doorway that gives us a strong sense of being separated by distance from the projected images of trees. The narrow doorway however, rather than being an image of somewhere out of reach, could also represent the gaps in time where we can see the meeting point of humans and trees – and how our fast-paced lives continue past these gaps without noticing because of the different speeds in time in which we and trees exist.

Choi also plays with mediums, using video to capture slow panning shots in ‘Forever and a Day’, giving it a photographic character at first glance, while contrastingly using photography to capture images created by movement in ‘The Other Side of Illusion’, where the works look more like film still shots. We do not know what these images are; all we see are certain surroundings captured while on move. The impression created here is of a haunting sense of not knowing, for we fundamentally believe in photography supposedly being the most accurate medium in its portrayal of reality. These photographs also question and explore again the visual representation of how fast humans live, too fast for us notice the spiritual coexistence between us and nature.

Choi delicately leads our thoughts towards the idea of pausing our hectic daily life and to take the time to be aware of this eternal synchronicity and the serenity that exists between us and nature.

Cheri Pitchapa Supavatanakul

Cheri Pitchapa Supavatanakul