Sandro Chia – Beyond the Avant Garde

In 1979 art critic Achille Bonito Oliva coined a new term Transavantguadia (or “Beyond the Avant Garde”) to describe a group of young Italian artists he saw as “moving beyond” the conceptual and politically-driven work predominant in Italian modernism through the late ‘60s and ‘70s. This loosely gathered group of artists included Francesco Clemente, Mimmo Paladino and Sandro Chia amongst others, whose work can be viewed as a rejection of political or ideological messages in a work, and a revival/return to traditional painting techniques and the subjective, impressionist touch of the romantic painter. The experimentation and novelty championed in the notion of the avant-garde subjugated artistic form to the Darwinistic mandate that art must continually advance. By measuring worth based upon newness itself the avant garde excluded the subjective, interpretive and personal dialogue within the canvas.

Spotlighted in the 1980 Venice Bienannale this group of individuals received a rapid rise in the wealthy arms of the ‘80s art world. So the impetus of Transavantgardia to devolve the constant surge-forward of the avant-garde nonetheless became itself a new artistic elite, with its members well-entrenched in institutions throughout the world. However the return to painterly skill as a positive value for art as in the work of Sandro Chia did not equate to an open-embrace of a booming art market, and his politics of practice remain key to what makes up his work.

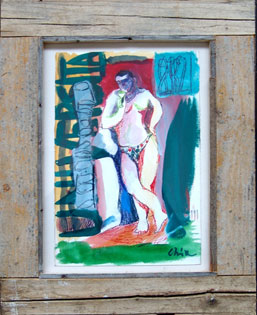

The current exhibition by the Istituto Italiano di Cultura, Tokyo shows new works by Chia painted primarily in the last year. The monumentality, aggression and intensity of Chia’s work in the ‘70s and ‘80s transitioned in the ‘90s toward a soft-cubism reminiscent of Picasso. The ‘90s works held more toward hard outlines and dense coloring, while recent works of the ‘00s have moved toward a round softness not unlike Chagall. This calm, if not subdued, style beginning of late seems less personal, less legendary and more focused on the somewhat bland everyday. With rich primary colors and a more mature yet still overt masculinity, these latest works are figure studies with reoccurring themes for Chia of angel wings, Romanesque faces and Christ figures. New touches are an interest in the full female and a nice smattering of sometimes lethal phalluses. While in Chia’s ‘80s works one sees domination of the muscular male on the canvas, to the exclusion of the female. This new collection shows a renewed interest in women, albeit at times borderline misogynistic: among the variety of poses some ambiguously resemble a disinterested strangulation or beating.

Upon viewing Chia’s work the immediate sense is of Classicism and Romanticism, a claim Chia himself is likely to support. This reviewer sees his work as two-fold: to learn and support great modes of art history (while not limited to the linear progression defined by modern art’s need for experimentation), while emphasizing a need to “metabolize” those modes through interpretation. Chia, who maintains studios in Italy and the US, is a tireless worker who spends almost every day in studio. Surprisingly, he does not paint models or outdoors, preferring a studio filled with drawing and paintings spanning art history. Chia draws from a mélange of images, things printed from the Internet and magazines next to the old masters, fold drawings and twentieth century art. This practice of metabolizing the mountain of images around him allows Chia to create his own imaginary artistic world that is “rooted in the profoundly personal subjectivity of the ‘immaginario’”.1

Where will this ‘metabolization’ of images take Chia? One wonders if the return to classicism as a rebuke to conceptual art’s “progress for progress’s sake” remains more than conservativeness or is actually able to maintain an active relationship through the “depolitization” of the canvas thirty years later. Isn’t the Transavantgarde’s gesture to “go beyond” simply emblematic of a postmodernizing trend of art in the 80s: to discard art of social politics for an unavoidable acceptance of late-capitalism? In seeking to surpass the conceptual avant-garde, Chia’s work remixes images at will (simulacra), while apolitically affirming subjectivity and individuality all in a fairly lucrative and stable mode. We can take pleasure in the self-exploration taking place through these works while also acknowledging their status as the harbinger of Art as an socially uncritical commodity. As his son stated, Chia “quotes the greats from history, makes a lot of money. ”2

2 Interview with author, 11/24/09

Kenneth Masaki Shima

Kenneth Masaki Shima