Inside Out

Why is it that industrial objects can remind us so much of living creatures, asks Shunji Yamanaka, designer, professor and exhibition director for “bones”, running till the end of August at 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT.

“bones” seeks to unite the industrial and the organic by swapping the ways in which we might approach these objects: organic remains become design objects, and design objects are re-interpreted as organic, evolved structures, sometimes creatures.

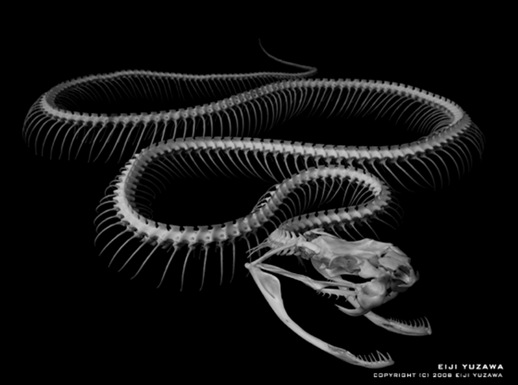

On theme almost to a fault, “bones” begins with a descent down stairs of sterile concrete. We are accompanied by Eiji Yuzawa’s photographs of animal bones, an imitation of a museum catalogue but transformed by Yuzawa’s deep shading. His photographs expose the irregularities and oddities of evolution, especially the facial structure of a small mole, which looks more alien than earthly.

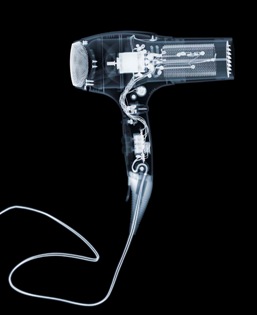

Beyond the first works and into a small room, Nick Veasey’s exceptional X-ray photography of everyday objects is on display. Here, a typewriter is given teeth, a hairdryer disguises itself as the gun found by airport security. Veasey, who hails from Britain, says that, unlike medical X-rays, “with industrial products it is the flow of energy and information and the communication of motive power that is exposed.”

In the same room, ‘Wahha Go Go’ sits madly grinning. A creation of prolific and peculiar art unit Maywa Denki, the toothy robot’s explicit function is to imitate human laughter, at which it fails exquisitely. With its whining breath it strips away the mental complexity it hopes to imitate. Here we see not a machine stripped down to its bare essentials, but a human function reproduced with minimal parts. It is a gross experiment, to treat laughter as a “vibrational phenomenon,” but an engrossing one.

Also worth noting is Brazilian visual artist Ernesto Neto’s ‘Mientias Estamos Aqui’, a lugubrious building inside a building that seems to hang in the space it fills, rather than enclose it. I’ve seen more ambitious works by Neto at other galleries, but his tent-like structure is strikingly appropriate here, appearing to grow inside the room.

The last major work in the exhibit is a collaboration between Automata Master Shobei Tamaya and director Yamanaka, entitled ‘Skeleton automata YUMIHIKI on a boat’. The elegant, wooden automata performs the incredible function of plucking an arrow, loading it to a bow, and hitting a target a few feet away.

As an exhibit, “bones” asks: by burying dynamic gears and cables under a smooth exterior, do we make our mechanical toys more human, or less? Is it, as Maywa Denki attempts, that by distilling function and form down to a single purpose we can imitate the complexities of living? Or, as Nick Veasey asks, by exposing the insides of the machine do we make it something more alien? What is it, for instance, about Veasey’s photograph of a Boeing 777 that causes, contrary to Veasey’s stated purpose, my architect friend to point out, almost instantaneously, the face apparent in the layout of the cockpit?

Yamanaka weighs in at the start of the exhibit: “Extracting the bones or the underlying structure of animals seems to accentuate the esprit of living organisms.” Contrariwise, “when we gather together the structures of industrial products, we…see the sequences of parts drawn up together to move in unison towards a common goal, and the traces of evolution occurring over years of innovation upon innovation.”

Matthew Hayles

Matthew Hayles