The Changing Faces of Japan

Living in Tokyo is an exercise in looking at multitude. Often impressions here are formed by ‘not seeing’, by passing over the diversity and unbalance that exists around us. We draw out landmarks from the cityscape, beacons we use to demarcate paths of familiarity without being conscious of how the urban space guides our everyday consciousness.

Yutaka Takanashi’s work creates a biographical record of Tokyo and its residents. The world within his viewfinder gives the sense of a greater composition that extends beyond the focal center to include details to the extremities of the frame. Although employing a number of different methodologies his lens is consistently focused on the minutiae amongst the mélange. In one work from ‘Tokyoites’ for example, black suits crammed into a train car dominate the image, the small headline on an exposed corner of newspaper giving subtext to mood of the scene: “Public Opinion on America…”

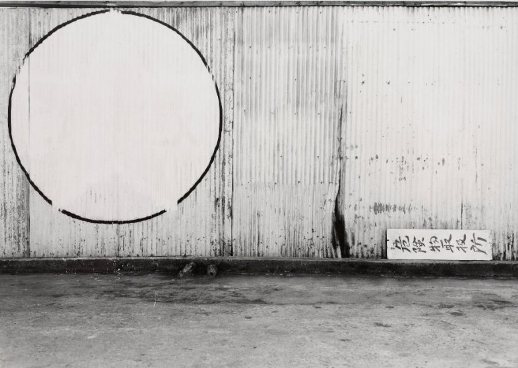

His earliest series in this current exhibition, ‘SOMETHIN’ ELSE’, is the most visually abstract. A solo show held at the Ginza Gallery in 1960, it portrays cityscape by focusing on superficial form. Monochrome images of the city’s solitary geometry are captured in a soft, diffused light and shot straight on. These works are almost devoid of people, accentuating the pure figurative beauty of falling scraps of cloth or shadows across a common commercial façade.

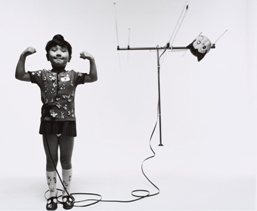

During the early 1960s Takanashi developed a reputation as a commercial photographer, winning awards for his advertising works. Throughout 1964 the portrait series ‘Otsukaresama’ appeared in Camera Mainichi magazine. In it popular media figures act out their public personas against a white background, dislocating their character from the familiar media environment while foregrounding the ‘mask’ of public image and cult of personality inherent in the rise of television culture. Flexing her muscles, child star Yukari Uehara is literally plugged-in to the television aerial through which her popularity is ‘strengthened’.

During the early 1960s Takanashi developed a reputation as a commercial photographer, winning awards for his advertising works. Throughout 1964 the portrait series ‘Otsukaresama’ appeared in Camera Mainichi magazine. In it popular media figures act out their public personas against a white background, dislocating their character from the familiar media environment while foregrounding the ‘mask’ of public image and cult of personality inherent in the rise of television culture. Flexing her muscles, child star Yukari Uehara is literally plugged-in to the television aerial through which her popularity is ‘strengthened’.

Pursuing non-commercial projects, Takanashi began searching the city with a smaller 35mm camera and wide-angle lenses (21-28mm), taking snapshots of the city’s residents. These images culminated in the highly recognized series ‘Tokyoites’ in 1966. Takanashi’s mentality for this series was something between “a hunter for images” and “a scrap picker,” he said. We see in these photos young families and the overlap of generations, lifestyles and landscapes that all co-existed during this period of booming capitalization. Lacking the critique of consumerism and reification of the subsequent ‘Tokyoites 1978-83’, this first ‘Tokyoites’ portrays a people still in ambivalent awe of the rapid change in their society, and less of the contradiction mixed with complicity present in the later series.

In 1968 with Takuma Nakahira and others, Takanashi co-founded the photography and criticism magazine PROVOKE, with the subtitle “provocative materials for thought.” However, Takanashi’s works stood in contrast to Nakahira and Daido Moriyama’s work, known for being “aré, buré, boké [grainy, blurred, and out of focus],” a style that dismissed previous photographic conventions in framing and shooting, snapping without using the viewfinder and having images of unaligned and unbalanced composition. Takanashi’s style is different, being grounded in the realistic image, though it still contains its own elements of subversion, and as a group the contributors to PROVOKE had a large influence on photography.

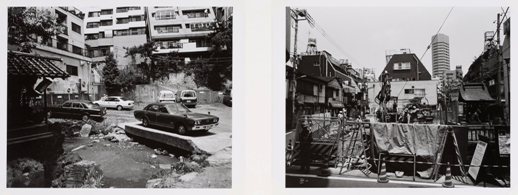

‘Hatsu-kuni: Pre-landscape’ (1983-92) searches the rural regions of Japan for religious iconography and traditional ceremonies — landscapes of pre-modernity. ‘Chimeiron: genius loci Tokyo’ (1994-2001) is perhaps the most difficult series: the works are paired shots of cityscape based around a specific area (loci) of Tokyo. However, the spaces are not ‘attractions’ in the conventional sense, but just spots buried in neighborhoods or parallax views of the same stretch of street. They attempt to convey the prevailing character of their place and here we see another example of minutiae — not something necessarily small but rather commonly thought of as trivial.

Recently, Takanashi has focused on the relationship between residents and the boundaries and pathways created within urban spaces. ‘Windscape’ emphasizes the image impressed on our mind from a sudden glance from a train. Presented as a slide show the viewer has only brief seconds to grab each image before the slides advance, emphasizing that intuitive or impulsive moment of snapping the shutter Takanashi himself experienced. The most relevant series for current Tokyoites is ‘Kakoi-Machi’ (2005-6), whose wall-sized images foreground barriers, grids and borders normally unconscious – construction barriers, mock-up posters, nets and patterns of light all of which confine and define the space around us: the process of which we rarely consciously see.

Through Takanashi’s lifetime of works questions are posed about the nature of change in Tokyo — of space and patterns of lifestyle, and of how much of our world remains unseen. We see here patterns of work and consumption that physically and psychologically create boundaries for our ability to see. This formulation gives us the power to transcend our patterns and makes us conscious of what we were unaware.

Kenneth Masaki Shima

Kenneth Masaki Shima