Drawing Life from a Simple Metal Sheet: Gyokusendo

Tsubame City in Niigata prefecture is a metalworker’s town. Blessed with both raw materials and tools since long ago, the metalsmithing techniques that developed here are now known nationwide. Among these, one beautiful local craft that has made a name for itself not just within Japan but also overseas is the hammered copperware called tsuikidoki. This two hundred year-old technique of pounding flat copper sheets into three dimensional goods such as kettles and teapots has been elevated to a fine art. One manufacturer that still operates today is using these techniques to create beautiful modern pieces. Gyokusendo was founded in 1816. The company has been participating in the Japan Brand project since 2004, in collaboration with other Tsubame manufacturers to produce their “

Interviewed by Reiko Yamamoto. Edited by Takafumi Suzuki. Translated by Claire Tanaka

Q: I understand Gyokusendo has quite a long history. Could you tell me a bit about that?

A: Tamagawa: They say that Tsubame’s metalworkers produced the original Japanese nail during the early years of the Edo period. There’s a copper mine nearby called Yahikoyama, and good quality copper was mined there. Tsubame became a production area for copper goods because it was so well-placed. They say the method for making tsuikidoki (hammered copperware) was taught to the founder of Gyokusendo, Kakubei Tamagawa, by a travelling craftsman from Sendai. That’s where the history of our craft starts, but in fact the tsuikidoki industry nearly completely dissappeared for a period. This was due to shortages of copper during the Second World War. The man who brought it back was this company’s fifth generation president, a man named Kakuhei Tamagawa. After the war, he sent out a call to all the craftsmen who had dispersed throughout the country and brought them back to Tsubame and rebuilt the tsuikidoki industry. That may be part of the reason, but our production techniques have been designated by Niigata prefecture and the Agency for Cultural Affairs as an Intangible Cultural Asset. Mind you our techniques aren’t the only thing we’ve got with historical value. In fact our building here is also registered by the Agency for Cultural Affairs as a Tangible Cultural Asset.

Q: What kind of processes go into the production of tsuikidoki goods?

A: Tamagawa: First, we use a wooden mallet to pound a copper sheet into a circular shape. The copper sheet is just 1.2 millimeters thick. After that, we place the copper over a tool called a toriguchi which is a sort of metal bar, and move the copper ever so slightly after each strike with a metal hammer. This technique causes the copper to shrink, and a vessel shape can be made. The trick is to strike the copper in such a way so that the strike marks don’t overlap. Another important phase in the making of tsuikidoki is the annealing process. The hard copper is heated in a furnace until it softens, making it easier to form. This annealing process is repeated many times during the forming of a single piece. A piece is complete when the entire surface has been beautifully contoured by the blows of the hammer. Depending on the product, we sometimes do engraving on the piece after the shaping is complete. Other pieces have a final step where the metal is given a patina. It takes quite a long time to complete a piece: about one week.

Q: You certainly have a lot of hammers and toriguchi.

A: Tamagawa: We’ve got about two hundred different kinds of hammers, and about three hundred different kinds of toriguchi. The reason why we have so many is that we’ve got to change our tools depending on what kind of shape we want to make. The artisans here have a tool for everything. For example, to make just one kettle they’ll use twenty to thirty different toriguchi alone. Of course each toriguchi is handmade by the artisan himself. We still have some that have been here since the founding of the company approximately two hundred years ago. I think the thing that many visitors notice when they watch the craftsmen at work is their work stool, called an “agari ban.” It’s not only a place to sit while you work, but it also has the added function of being able to hold the toriguchi. The stool is a section of a zelkova log and it’s very tough wood, and several toriguchi can be inserted into it at one time, making it possible to work in a very efficient fashion. Plus, they don’t wobble – they’re very stable.

Q: To create a three dimensional object from a flat sheet of metal must take the skill of a real master.

A: Tamagawa: For a craftsman to learn all the techniques involved can take from twenty to thirty years. In our case in particular, we don’t split up the work, so each craftsman must take responsibility for his own work from start to finish. The first challenge is to learn how to strike the copper plate so that it shrinks into a three-dimensional form. It’s hard to make the copper contract, and in fact it tends to get even more stretched-out. But a proficient artisan can make a kettle from one sheet of copper without any seams at all. The younger staff still have a long road ahead of them. At first, they learn to make objects with simpler shapes like sake cups. The younger staff here are all working really hard. That’s why we keep their progress in mind and leave the studio open so they can come in after work and on their days off. They’re in here night and day pounding metal. They want to learn all the tsuikidoki techniques as quickly as possible.

Q: I understand that your techniques for coloring the metal are also unique to Gyokusendo.

A: Tamagawa: One feature of our style is the beauty of the surface oxidization. We fuse tin onto the surface of the copper and soak the pieces in natural liquids like potassium sulfide which adds a nice patina. Then we add a coat of wax for shine. This method of coloring the metal can be manipulated to create a wide variety of colors. The mix of liquids and length of soaking can produce different shades. The methods we use are our very own, and I imagine we’re the only ones in the world who know these techniques.

Q: Speaking as a copper goods manufacturer, what would you consider to be some of the good points of copperware?

A: Tamagawa: I’d have to say the best qualities are its ability to give the user good water, mellow tea, and mellow sake to drink. Copper has antibacterial properties, and it purifies the water. With copper teapots and sake cups, the copper ions mellow the flavor of the tea and sake. When we have sales exhibitions at department stores we hold samplings with our teapots and sake cups, and the difference is very clear. Another feature of copper is that over time it becomes even more lustrous, and the flavor it lends becomes more full and rich. But of course you’ve got to always wipe it with a dry cloth.

Q: Next, could you tell us a bit about your involvement with the JAPAN BRAND project?

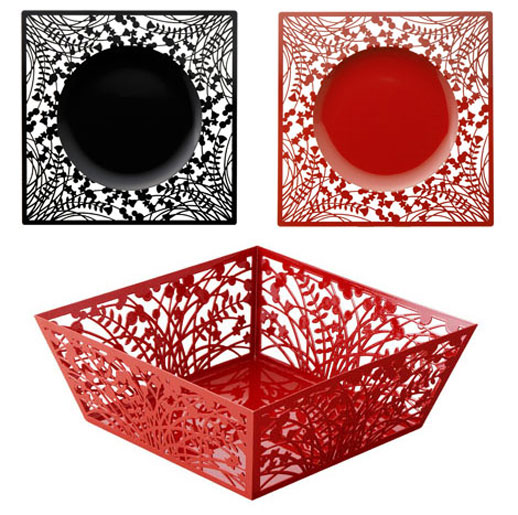

A: Tamagawa: There’s a brand called “enn” which we’re acting as product producers for. There are six Tsubame metalwork manufacturers participating in the project. The person in the position of tying all six companies together is the president of a Tsubame-based company called Kitchen Planning. His name is Shoichi Myodo and he’s here with me today. We commissioned graphic designer Hitomi Sago to develop the designs for the brand, which was developed for the overseas market with a concept based on Japan’s food culture, called “Japanesque Fusion.” There are two separate lines in the brand, one consisting of metal dishes and cutlery coated with lacquer, and another line of simple tsuikidoki copper pieces.

Myodo: Japan’s food culture continues to take the world by storm. Even within French cuisine, Japanese techniques and ingredients are becoming prevalent. Despite this, many top chefs complain that “there isn’t any good tableware available that can properly accentuate this Japan-influenced cuisine.” The enn products fit this need perfectly, and our project has gained acceptance from them. For example, we showed our lacquered cutlery line to Joël Robuchon, and he fell in love with it immediately, and now his selection can be seen in the shops and restaurants of Paris.

Q: The lacquerware series certainly does create a strong impression.

A: Myodo: I think the line has such an impact because we comissioned not a product designer, but a graphic designer with a lot of experience in commercial advertising for the design. I think that someone who is quite familiar with this kind of product and with the local industry could never have come up with such a design. Someone who doesn’t know the industry well is in a position to come up with fresh ideas and attract attention. The company that applies lacquer to the metal is actually a local Niigata lacquerware manufacturer. We looked into it and found that from the metal treatment aspect, this manufacturer right here in our own prefecture was best suited for the job both technically and cost-wise. We had originally thought we’d collaborate with a lacquer producing area in another prefecture, but the costs didn’t add up…

Q: It seems as though you are trying to make more of an industrial product than a traditional one.

A: Myodo: Yes, that’s right. It’s not quite an industry, but we’ve finally got things set up for mass production. Up to now, we have been developing what you could call “flagship products” with the enn project. Using handmade techniques to help our products to stand out; creating products that can lead the brand. But the next step is to put down roots in the producing area here. The tsuikidoki copperware, which has quite a good reputation overseas, is prohibitively expensive. With the amount of labor that goes into it, that can’t be helped. But if a network can be built up in the producing area, that situation can change. What if we introduce presses and other machines and make a composite product? In fact, right now Gyokusendo is acting as a point of contact with the local tsubame-doki cooperative and we’re working towards creating a system where we can do manufacturing with their cooperation.

Q: What do you consider important when thinking about how to improve this collaboration?

A: Myodo: One important thing is that the maker and the customer have a similar sense of value. It doesn’t matter how lovely you think your own product is, if there’s no need for it in the market, there’s no point. That is where distribution issues come in. At Gyokusendo, the craftsmen make each piece themselves from start to finish, and sell their goods directly to small retail shops. They are in a position to hear the customer’s thoughts and opinions directly, and apply that to their next product. They’re natural practitioners of direct marketing. In order to do that, the seventh generation owner cut out the middle distributor and switched to a direct sales system. I think that was a huge decision, and it must have taken a long time. But, building up a brand isn’t just about making things. It’s also about building up production and distribution. That’s why the enn project has put the Gyokusendo way of doing business into practice.

Gyokusendo Chuo-dori 2-3064, Tsubame City, Niigata

A Word from a Regional Project Participant

The JAPAN BRAND project that I joined through the Tsubame Chamber of Commerce and Industry will enter its fifth year this year. The first year consisted mainly of market research and concept development. We started out by having the participating companies think about “what is a brand?” and established a core group of companies with a shared awareness and a true desire to engage in the project. Now there are about ten companies involved, but at first there were only three – one of which is Gyokusendo, which has emerged in a leading role in the project. Once we clearly developed our tableware brand “enn” based on a sort of “Japanese Modern” concept, the next step was to develop a strategy of how to develop it as a regional brand. Metal western-style tableware is not traditionally Japanese, so we realized that if we were to sell ourselves as a Japanese brand, we were going to have to find a way to connect our products to a Japanese sensibility. That was when we hit on the idea of making lacquer-coated metal pieces. This was then recognized by some top world chefs including Joël Robuchon, and now in our fifth year, I believe we’re positioned to take a new place in the food culture market. Our products have been brought into use at famous restaurants overseas, and nearly all the large domestic department stores carry our brand. We’ve also been approached by fashion brands and cosmetics manufacturers in Europe asking if we might do collaborative projects with them, and we’re now considering how we want to expand our activities. In the past five years, we’ve been working to differentiate ourselves through our difficult-to-imitate handmade products, focusing mainly on flagship items. Now that we’ve achieved a certain level of visibility in the market we’re going to start putting more energy into sales and distribution mechanisms, and we’re also setting our sights on getting the whole production area involved in our project.

Japan Brand

Japan Brand