Art in a Handful of Dirt

Vik Muniz has made a career out of his inventive use of materials, everything from chocolate sauce to peanut butter. This show at Tokyo Wonder Site, Shibuya, comes off the back of the big Brazilian show “Neotropicalia” at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, and runs alongside the Muniz-curated show “Haptic”, at Tokyo Wonder Site, Hongo, and Misako and Rosen Gallery’s small showcase of Brazilian contemporary sculpture. It is a small but adequate introduction to some of his projects.

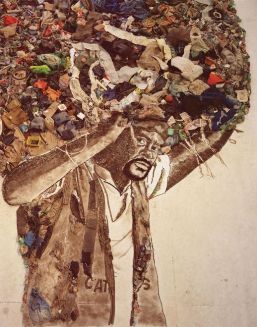

The space is divided between two floors; in the foyer you are met by three ‘reproductions’ of Picasso, all quite large and colorful. All right, so you are already a little off-guard. In the next room you find the bulk of the exhibition – ‘Pictures of Garbage’, a series of pseudo biblical and classical ‘paintings’, constructed out of, well, junk and refuse. Even my essentially untrained eye picked out some images I recognized. The whole thing, on top of its visceral zest – the brown tones, the subjects banal, downcast and heroic – feels like a postmodern joke. An adjacent room contains a video showing in high speed the manufacturing of Muniz’s epic and highly skilled ‘fakes’.

The subject matter for the ‘Pictures of Garbage’ is the downtrodden underbelly of Brazil, the poor class of catadores ‘dwelling’ in massive garbage dumps. Shaping these people into classical figures like Atlas or seemingly quasi-versions of real paintings not only gives resonant visualization to them, but by representing them in the very ‘material’ of their surroundings Muniz is arguably not simply exercising a political polemic but radically developing the often merely superficial dimensions of Pop Art.

The subject matter for the ‘Pictures of Garbage’ is the downtrodden underbelly of Brazil, the poor class of catadores ‘dwelling’ in massive garbage dumps. Shaping these people into classical figures like Atlas or seemingly quasi-versions of real paintings not only gives resonant visualization to them, but by representing them in the very ‘material’ of their surroundings Muniz is arguably not simply exercising a political polemic but radically developing the often merely superficial dimensions of Pop Art.

Venturing upstairs, you are met by dozens of photographs of Muniz’s vast ‘Pictures of Earthwork’, where with diggers he carved shapes into the plateau of hills in South American mines, and then photographed them from the air. Here, though logistically astounding, Muniz has departed from the sociological landscape of the ‘Pictures of Garbage’ for the realm of the fun, almost the childish – the shapes include umbrellas and paper aeroplanes.

The other series of photographs upstairs are of his ‘Pictures of Cloud’, where he went one step further in his development of the artistic process. He used skywriters to draw large cloud images in the air above urban areas. At first glance, these recalled Cai Guo-Qiang’s Hiroshima-themed ‘Clear Sky Black Cloud’ (2006). However, any resemblance is cursory, for they lack – or without any gallery guidance to suggest otherwise, they appear to lack – any message or significance like Guo-Qiang’s pacifism.

However, we should not be quick to criticize Muniz for lack of sincerity. He has his tongue firmly in his cheek but he has also done much to raise awareness of environmental issues, as well donate many funds to charitable projects. His approach has been called ‘subversive’, and indeed you can interpret the works as a meditation on the nature of perceiving an artwork (just as Marcel Duchamp et al did). More complexly, they are simulacra of paintings so famous and copied they have become as disposable and owner-less as refuse. Or is it an attack on our wasteful (literally waste-full) world? The current exhibition at the Mori Art Museum, “Chalo!” (reviewed here by Rebecca Milner), also features an impressive artwork made out of rubbish, though that was a

Those not knowing anything about Muniz might not understand exactly what has been produced, and the lack of exhibition explanation does hamper appreciation if one does not recognize the famous painting being copied. The video ‘Moving Junk’ downstairs gives you a quick and impressive run-down of the process, and there is also a television upstairs playing ‘the-making-of’ footage for the ‘Pictures of Earthwork’. The titles of the pieces go some way to rectifying this but certainly the works on the second floor, especially the photographs of the sky drawings, are essentially oblique to the unsuspecting visitor. (However, this may be deliberate, and Muniz has been criticized in the past for not giving enough credit to the works he copies.) Work that presents and provokes questions, and evades easy labels is often among the greatest art being produced, but curation must allow as many visitors as possible to arrive at those questions at least.

It is the ‘Pictures of Garbage’ that are the centre-pieces and the pieces that really impress. Without consideration for the process (as opposed to the result) the other ‘works’ might disappoint. I use quotation marks deliberately, since, though I was for a while awed by some of the exhibits, when all is said and done, this show is actually photographs of past works, works whose scale or ‘happening’-esque timescale prevents actual exhibition, let alone re-creation. And with that, sadly, some of the power is lost from this otherwise highly stimulating show.

William Andrews

William Andrews