The Year in Art 2008 — Part One

As with every January for the past three years, Tokyo’s art scene began the year with Art@Agnes, a compact art fair held in the luxury Agnes Hotel and Apartments in Iidabashi (see photo report). With 33 galleries occupying all available rooms and the basement hall, the building was entirely given over to the art market. Last year had become too crowded to function well as a place for art buying, and so visitor numbers were restricted to 2,500 over the two-day weekend. Likewise, last year too many galleries had attempted to cram their rooms full of as much work as possible, so for all the event’s compactness, it was a tiring visual slog. This year, however, Tokyo’s young galleries took the lead in establishing a less-is-more approach to their displays: Take Ninagawa opted for a solo show of New York-based painter and sculptor Misaki Kawai and Mujin-to Production showcased the work of riotous artist group Chim↑Pom, who were recurrent features of the Tokyo art scene this year. Citing that it has achieved its goal of establishing a new and fresh art fair in Tokyo, the Art@Agnes committee have declared 2009’s edition of the event to be the last, with plans for it to evolve into a new, as yet unspecified event in 2010.

In the commercial gallery circuit, Tokyo Gallery + BTAP began the year with “Regeneration”, its second solo exhibition of English artist Jane Dixon (artist interview here), showcasing new drawings and prints that explored notions of remembered space in cities destroyed by natural or manmade disasters — Tokyo and Yokohama included. At SCAI the Bathhouse, Thai video artist Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s “Replicas” was a poignant portrait of day labourers being transported across the country on the back of pickup trucks (reviewed by Darryl Jingwen Wee) and Gallery Koyanagi showed enigmatic family album-like photos by Hanayo.

Gallery buildings come and go

January also saw the first of several changes in Tokyo’s gallery map this year. Not far from Art@Agnes’ premises, the Kagurazaka gallery building (a former print warehouse) had seen two of its three tenants — Kodama Gallery and Yamamoto Gendai — leave to establish bigger spaces in a new building in the upmarket Shirokane-Takanawa neighbourhood (see photo report). This new gallery complex houses a second space for collector Ryutaro Takahashi’s viewing room Takahashi Collection, which is also located in Kagurazaka. On the opening night, while Kodama Gallery held “Bi-Bi-X” a solo exhibition of Zon Ito’s thread-on-canvas works (reviewed by Darryl Jingwen Wee) and Yamamoto Gendai held “Dream of the Skull”, a group show of its artists, Takahashi Collection provided the most memorable display: Tomoko Konoike’s approximately ten metre-long multi-panel drawing of wolves exhaling clouds of daggers together with a large, mirror-encrusted sculpture of a six-legged wolf striding through a forest of wires stretched from floor to ceiling. This move into Shirokane does not mean that the Kagurazaka gallery building has closed, however: Kyoto-based gallery Mori Yu now occupies Kodama Gallery’s former space, nearby Yuka Sasahara Gallery moved into Yamamoto Gendai’s former space and Artlantico Gallery opened in the building opposite, preserving Kagurazaka’s status as one of several key nodes in Tokyo’s broadly scattered gallery scene.

On the other hand, early Feburary saw the closure of the Roppongi gallery building (see photo report). Opened in 2003 at the same time as the nearby Mori Art Museum, the poky, run-down building on Imoaraizaka Street offered cheap rents to five galleries and played a significant role in Roppongi’s recent gentrification from an area known only for its sleaze to a high-end destination for contemporary art and luxury retail. The building didn’t go out quietly: Magical Artroom staged a fierce noise music session and in a party titled “Force Quit”, Roentgenwerke’s director Tsutomu Ikeuchi gave a thumping koto drum performance.

Unlike the clean and coherent trading of gallery spaces that took place between the Kagurazaka and Shirokane buildings, however, the occupants of the Roppongi gallery building have scattered far and wide across the city. While this perpetuates the relative inconvenience of gallery hopping in Tokyo, one potentially positive development has come out of this: two of the former Roppongi galleries have relocated to the blue-collar neighbourhood of Bakurocho in East Tokyo, where they join a handful of spaces that were already there. Taro Nasu Gallery now occupies the same building as Foil Gallery and Roentgenwerke (now renamed Radi-um) finds itself next door to CASHI Contemporary Art. With spaces such as Makii Masaru Fine Art, Motus Fort and Parabolica Bis also already in Bakurocho, the neighbourhood is now something of a fledgling gallery district. Should more spaces open there over the next couple of years, Tokyo’s art scene could conceivably find itself grasping its holy grail: a relatively dense, walkable centre of commercial contemporary galleries.

Seas of stuff and sequences of space

In March and April, several eye-catching exhibitions were in full swing. Back in Ginza, the former undisputed hub of the Tokyo art world, Sarah Sze created a spectacular installation for Maison Hermes’ 8th floor gallery Le Forum (documented in a photo report by Paul Baron and reviewed by Olivier Krischer), filling the cavernous glass-walled space with a waves of office paraphernalia undulating across the floor and up one of the gallery’s supporting columns.

A similarly bold manipulation of space was attempted with architect-cum-installation artist Tadashi Kawamata’s “Walkway” at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo (MoT). Curated by Fumihiko Sumitomo, this ambitious exhibition aimed to deviate from conventional museum displays by channeling visitors through wooden corridors temporarily erected throughout the space, leading them to ad hoc workshops overseeing projects across the city. Throughout the show, black and white documentary photographs showed Kawamata’s past projects, such as a set of wooden beams and walkways weaving through the structure of a ruined stone church. Comparing such an exciting example of fluid architectural intervention with the static plywood panels of the walkways running through the MoT, I couldn’t help feeling that no installation could ever challenge, let alone subvert, the authority of the museum’s white cubes unless it were to literally break through the walls and envelop the façade and roof.

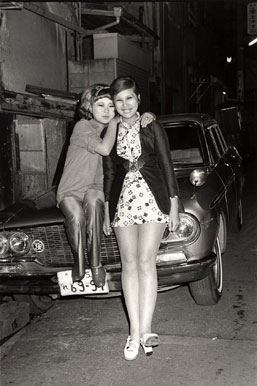

Meanwhile, the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art had bedecked the walls of its three floors with thousands of black and white images by the recently deceased photographer Katsumi Watanabe, charting the social history of Tokyo’s Shinjuku entertainment district from the 1960s to the early 2000s (reviewed by Vicente Gutierrez). Tadanori Yokoo’s “Be Adventurous” retrospective at the Setagaya Art Museum showcased vivid red, surreal visions of quiet Japanese backstreets and was preceded by a show of his new paintings at SCAI the Bathhouse (reviewed by Cameron McKean). Lastly, Tatsuo Miyajima’s “Art in You” exhibition at Mito Art Tower focussed on new work such as Hoto (2008) a towering, beacon-like mirroed sculpture of digital counters that conveyed the artist’s post-9/11 interest in creating art based on the idea that there is no difference between the artist and observer and all art is literally “art in you”. Although Hoto was an impressive work in its own right, it was not enough to carry the entire exhibition, which was overly reliant on uninspired photographs of digital numbers painted on human bodies, making for a disappointingly empty experience (reviewed by Olivier Krischer).

Tokyo’s art scene blossoms in spring

The first week of April was a flurry of art world activity: Tokyo was taken over by art fairs, art awards and numerous gallery openings for what was effectively the first Tokyo Art Week.

Art Fair Tokyo certainly improved on last year with a larger number of participating galleries offering simpler, more coherent displays of work; a few were even relatively adventurous in their presentation, such as Mizuma Art Gallery, which constructed its booth out of scaffolding and suspended a large, winged insect-like sculpture of a human heart by Tomoko Konoike. However, the most exciting of the week’s events was by far the inaugural 101Tokyo Contemporary Art Fair, the city’s first satellite art fair, located in a former high school building in Akihabara (see photo report). Created by Julia Barnes of nonaca/Nakaochiai Gallery, Kosuke Fujitaka of Tokyo Art Beat/NY Art Beat and independent curators Agatha Wara and Antonin Gaultier, 101Tokyo aimed to be the antidote to the domesticity and conservatism of Art Fair Tokyo by featuring 28 young galleries — 14 from Japan and 14 from abroad — and injecting a sense of fun and unpredictability into Tokyo’s art market with a lively program of talks, performances, awards and parties.

Instead of opting for the shopping mall-like layout of corridors that typifies art fairs around the world, 101Tokyo experimented with a grid of interconnected booths. This was met with a mixed reaction as indeed it made for a more meandering art-viewing experience and encouraged interaction with gallery owners, but coupled with the venue’s low ceiling it also felt claustrophobic and relentless, depriving buyers of much-needed moments of private pause to decide on a purchase. Nevertheless, the quality of work was generally high: stand-out gallery booths included Berlin’s Galerie Alexandra Saheb, with its solo show of Heiko Blankenstein’s striking green lightboxes depicting chaotic scenes with an aura of religious iconography to them; Newcastle’s Workplace Gallery, whose centerpiece, Jo Coupe’s Enough Rope — a bowl of fruit wired up to mini-buzzsaws cutting through the legs of the wooden table on which it was placed — went on to win the fair’s “Bacon Prize” for best artist; and Tokyo’s Gallery Naruyama, which displayed the eerie, supernatural oil paintings of contemporary Nihonga artist Fuyuko Matsui, among others.

In spite of being a brand new fair consisting only of young contemporary galleries in a small art market, 101Tokyo scored a relatively impressive sales total of 100 million yen ($1 million); Art Fair Tokyo on the other hand reported sales of 1 billion yen ($10 million) across its classical, modern and contemporary genres — the same figure reached in 2007, and stated on the AFT website as proof of stability in the market. Details of what proportion of this total came from contemporary sales were not provided.

Youth was key to the success of Tokyo Art Week (officially known as Marunouchi Art Weeks, designating the area where most of the events take place). Seven of Tokyo’s youngest commercial galleries — Arataniurano, Aoyama Meguro, Misako & Rosen, Mujin-to Production, Take Ninagawa, Yuka Sasahara Gallery and Zenshi — formed an association called “New Tokyo Contemporaries” and their first collaboration resulted in “End of the Tunnel”, an atypical mini-art fair held on the 7th floor of the Shin Marunouchi Building that saw art works installed in and around the restaurants on that floor (see photo report).

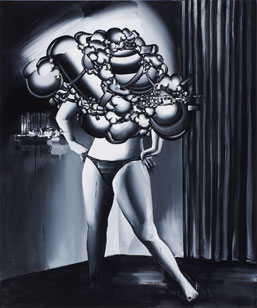

The cluster of galleries housed in the Kiyosumi-Shirakawa complex held simultaneous openings of solo exhibitions that week (see photo report): Taka Ishii Gallery held a superb show of Tomoo Gokita’s haunting, semi-surrealist black and white oil paintings in which figures and still lifes have been abstracted and distorted by curved sweeps of the brush; Hiromi Yoshii presented “I Have Meant”, a display of New York-based Nick Mauss’ intimate domestic scenes engraved in silver foil on panel; and in “The Restless Subject”, Shugoarts showcased a video projection, some wall-mounted neon light works and photographic scenes on light boxes by Runa Islam. This month also saw the 33rd Ihei Kimura Photography Award given to Atsushi Okada for his cold white portraits of self-harming Japanese youth and Lieko Shiga’s equally enchanting and nightmarish portraits and landscapes in which nothing seems as it should (artist interview here).

Such a period of heightened activity was ideal for the launch of two new guides to the city’s art scene. After many months of intensive collaboration with Craig Mod of Chin Music Press, I published Art Space Tokyo, a 272-page guide to 12 of the city’s most architecturally and historically distinctive galleries and museums (to coincide with Art Fair Tokyo, an extracted interview with its executive director, Misa Shin, was published on TAB, here). Tokyo Art Beat released the Tokyo Art Map, a bimonthly, bilingual mini-guide to exhibitions taking place in key art areas around Tokyo. Last but not least, New York Art Beat was launched, offering comprehensive listings of art events taking place in that mother of all art scenes.

Tokyo in Tokyo and Tokyo in New York

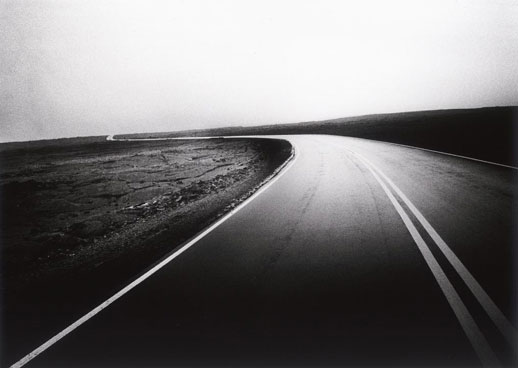

Key exhibitions in May included Naoya Hatakeyama’s “Ciel Tombé” at Taka Ishii Gallery, presenting new photographs taken in the catacombs underneath Paris (artist interview here); Zenshi’s compact but compelling solo show of Shigeru Suzuki’s mixed media imagery, titled “Human”; and the Buddhist bondage of Ken Hamaguchi’s “Black, Sutra, and the rest” at Takahashi Collection (reviewed by Lena Oishi).

Courtesy of the artist and Taka Ishii Gallery

Courtesy of the artist and Taka Ishii Gallery

While the Mori Art Museum’s main show during May was a retrospective of Britain’s Turner Prizewinners (reviewed by Gary McLeod), it was its MAM project space that held the true gem: two of Saskia Olde Wolbers’ ethereal, hypnotic video works filmed in otherworldly settings — each work a decade in the making — with dream-like narrative voices telling forlorn stories of love, deceit, longing and loss. She also had a solo show running concurrently at Ota Fine Arts (both shows reviewed by Andrew Woodman).

During a ten-day visit to New York to begin promotion of Art Space Tokyo’s US release in September, I found a number of high-profile exhibitions of Japanese artists. “Heavy Light – Recent Photography and Video from Japan” at the International Center of Photography brought together major names such as Naoya Hatakeyama, Makoto Aida, Tsuyoshi Ozawa and Miwa Yanagi. Following its stay at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, Takashi Murakami’s aptly titled retrospective “©MURAKAMI” had arrived at the Brooklyn Museum. Both of these shows left me feeling an unusual sense of cultural distance. “Heavy Light” was an engaging exhibition, but knowing that one never sees these artists’ work displayed together in Japan—and there were a number of artists included, such as Hiroh Kikai and Naoki Kajitani who have no great presence in Japan—it felt detatched from the contemporary reality of the Japanese art scene. Meanwhile, Murakami never shows in Japan anyway, so his retrospective, while in many ways impressive in its own right, felt alien Japanese world of its own, utterly disconnected from developments in the Japanese art scene of the past few years.

Yoko Ono, on the other hand, despite being based in New York, exhibits regularly in Japan. Her solo show “touch me” at Galerie Lelong in Chelsea showed the artist continuing to encourage viewer engagement with her work, this time through the themes of the human body in fragments. In the centre of the gallery a large sheet of canvas full of holes had been suspended, and visitors were instructed to insert a body part through one of the holes, have a friend or another visitor photograph it with the supplied Polaroid camera, write a message on the photograph and pin it up on an adjacent wall. More poignant was Touch me III (2008), a latex sculpture of the female body divided up and placed in 9 black wooden boxes; visitors were instructed to wet their fingers in a little bowl of water and poke the latex skin. A note on the wall explained that the Ono had been shocked to discover how quickly the work had been damaged — its toes ripped off and holes left in the stomach by invasive, probing fingers — but had decided to leave it exhibited in this state as a testament to the pain of the female experience.

A giant handbag from outer space, sentient artificial flowers and a panda funeral

In June, Tokyo was abuzz with the news that the “Mobile Art in Tokyo — Chanel Contemporary Art Container” was coming to Harajuku. Previously in Hong Kong and due to travel to New York, London, Moscow and Paris, the futuristic Zaha Hadid-designed pod, built in the shape of Coco Chanel’s classic 2.55 quilt handbag, was installed next to Kenzo Tange’s National Stadium in Harajuku and housed 21 Japanese and international artists such as Tabaimo, Yoko Ono, Lee Bul, Subodh Gupta and Michael Lin. Viewers were required to purchase low-priced tickets and enter in groups of 20 and experience the exhibition with a timed audio guide that dictated the pace of their progress from room to room. Unfortunately, touts bought up the tickets en masse early on and attempted to sell them on at a higher price — a strategy that simply wasted viewers’ time as many refused to buy the tout tickets, resulting in standby queues of people who would eventually be allowed in when gaps appeared in the pre-booked groups. Having turned down an invitation to the opening on the assumption that I would be able to see the show like everyone else, the hassle of having to find a free time in a busy month that corresponded with weather good enough for standing in line outdoors meant that I ended up missing out on the show.

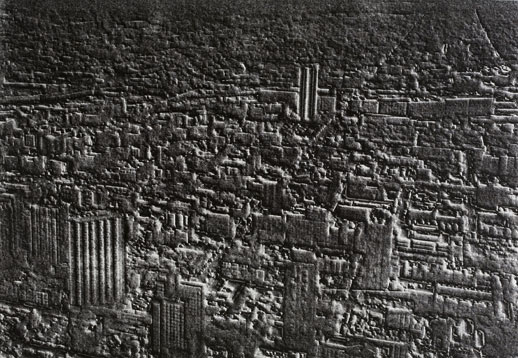

Back in the fixed spaces of museums and galleries, the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography was holding two exhibitions of the legendary Daido Moriyama: a retrospective charting his work from 1965 to 2005 and a show of his new photographs from Hawaii. This prolific photographer exhibits very frequently in Tokyo and abroad, and viewers are typically presented with either his newest work or his classic, most well known images from 1968 to 1972 — grainy, blurred black and white shots depicting gritty street life in Shinjuku, the epicentre of protest and counterculture during a period of sociopolitical unease in Japan. Thus the Museum of Photography offered a welcome opportunity to situate his peak of success within the context of his entire career, which included a creative slump followed by explorations of wilderness in Hokkaido during the 1970s, a return to studies of texture, light and shade in the 1980s, and more recent ventures to Buenos Aires and Hawaii, which have led him to experiment with colour photography.

Other exhibitions of note at this time were Choe Uram’s creepy installations in his solo show “Anima Machines” at SCAI The Bathhouse (reviewed here); “A Circular Play”, a funny and playful exhibition of conceptual art by Danish artists Nina Beier and Marie Lund at Wako Works of Art (featured by Katrina Grigg-Saito and documented in a photo report by Darryl Jingwen Wee); and Roni Horn’s “This is Me, This is You” at Rat Hole Gallery, which faced off two sets of 48 portraits of the artist’s niece, one set taken only seconds after the first (reviewed by Rachel Carvosso).

June was also punctuated by a couple of more low-key events of interest. Architectural group Assistant turned their Hatsudai studio space into a makeshift gallery to hold “Absent City”, a poetic meditation on human communication in the urban environment (architect interview by James Way). At Tokyo’s premier nightclub Le Baron de Paris, multimedia artist Nagi Noda, renowned for her Mariko Takahashi fitness video, held a funeral for Nyanpanda, the half-cat/half-panda in her “Han-panda” series of half-something/half-panda creatures. A funeral for a product held in a nightclub seemed only possible in Tokyo and was a ripe idea for the artist to take as far as she wanted. Unfortunately though, asides from the general creepiness of numerous giant han-pandas lining up to pay their respects to Nyanpanda in her open casket, it felt as though the event fell short of the totally surreal fantasy it could have been. In retrospect, however, it was a sad forecast of the future: in September Nagi Noda died at age 35, depriving Tokyo of a much-loved icon of irony.

Part two of this article, covering July to August, can be read here.

Ashley Rawlings

Ashley Rawlings