Yokohama Triennale 2008: Pedro Reyes

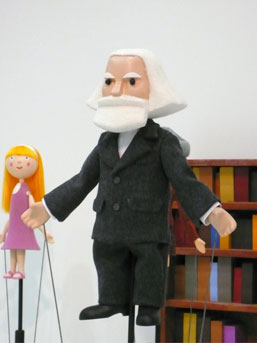

Pedro Reyes’ installation Baby Marx is one of the few works at the Yokohama Triennale to overtly mix politics and humor. Consisting of twelve rod puppets and some small props arranged on a wide shelf, we find the pantheon of the International Left in effigy — Marx, Engels, Lenin, Mao Tse Tung, Che Guevara — and other figures, youthful but anonymous. With their mechanisms exposed to view, we are invited to admire the craftsmanship of the puppets, and yet, the center of attention in Baby Marx is a lone video display, playing a seven-minute narrative drama — a shibai — of the puppets in a simple décor, with music, subtitles, and no dialog. In this piece, Reyes’ story begins in an empty library. Slow, wistful piano chords set the tone as a schoolmarmish woman with bobbed hair scans the shelves, gathering books. The subtitles tell us that: “Somewhere, sometime in the XXIst century [a] wise man said history had ended and ideology was to be no more. Lost forgotten theories of fancy social utopias now rest in oblivion.” The image dissolves into a close-up shot of the books stacked on a table behind a small sign that says “scheduled for disposal” [shobun yotei].

The situation is now clear: Reyes’ story begins in the present age, as it is characterized by the American political philosopher Francis Fukuyama. Drawing heavily on Alexandre Kojève’s reading of Hegel, Fukuyama claims that the end of the Cold War is not merely the end of one chapter in twentieth-century history, but “the end of history as such”. With the demise of the Soviet Union, Western free-market democracy has emerged as the definitive and final form of mankind’s political evolution. In The End of History and the Last Man, Fukuyama’s controversial thesis is that world history should be seen as coherent, teleological and, above all, universal. On his account, the European and American democracies represent the end point of human government, all other pretenders and ideologies having been defeated. Fukuyama affirms a uni-polar modernity modeled on the West, the spread of consumer culture, and the idea that all countries “must increasingly resemble one another”. Here, we may ask: does Reyes accept this narrative of universal history? The answer: almost certainly not.

For meanwhile, back in the library, a group of younger-looking characters enters the scene, bows, and a discussion begins. The woman with bobbed hair proves to be a teacher, explaining the books to her young charges. The students are cheerful, engaged, and apparently politicized (one is attired in revolutionary chic). The subtitles inform us that “something unexpected is about to happen“, and a new scene begins, showing the teacher and students on break from a history class. While the others cheer her on, one of the students heats a copy of Das Kapital in a microwave oven, provoking an explosion. As the smoke clears, a puppet figure of Karl Marx ascends into view, raising his tiny fist defiantly. With the heating process serving as a metaphor for historical inquiry, Reyes poses the oven as an “intellectual defroster” that enables the students to unleash “a unique group of thinkers and revolutionaries, from their mausoleums of paper“. The music shifts into a retro-cool 60s-vintage garage rock tune, as Marx, Engels, Lenin, Mao, and Guevara are each introduced with animated titles and snappy horizontal wipes. “They have come,” we are told, “to fight the last battle against the global empire of capitalism.” As if through a rupture in the continuum of time, the icons of the Old Left have been revivified, readied for action once again. The enemies of the Left are introduced as well: a dour Adam Smith, a rhythmically calculating Taylor, and a hypnotic Stalin each appear in succession. With his arms flailing comically, the puny Smith leaps into a vicious fistfight with the fatherly Marx. Successive shots show us Marx reading Das Kapital, Stalin gesticulating tyrannically, Guevara seducing the Schoolteacher, and finally the puppet-heroes lined up in a row, clapping and gesturing in unison as the subtitles summarize: “BRING ON THE REVOLUTION!!!”

Many visitors at the Triennale are openly amused by Baby Marx — indeed, it seems to be getting more laughs than almost any other work at Shinko Pier — but are we to take Reyes’ piece as an ironic treatment of the fate of the political Left? Well, yes and no. The work seems to oscillate between the serious and the ironic, and this is clearly part of its appeal. To a certain extent, its humor trades on the low burlesque of subjecting the heroes of the Left to a kawaii treatment, literally bringing them down to the level of puppets. Their gestures and movements evoke a comical quality that begins as something corporeal. For, insofar as the face of a puppet is static (in Baby Marx, the heads can rotate, but only Lenin’s mouth can move), the neck, arms and body become the vehicles of expression. Particular gestures are thus imbued with greater significance: the pert rotation of Adam Smith’s head stands in for the pragmatism of the “gloomy science”, Marx’s raised fist signifies insurrection, or the expansive sweep of Stalin’s arm suggests naked ambition.

This comedy of gesture and movement recalls Bergson’s notion that we are amused by the appearance of “something mechanical encrusted upon the living” [du méchanique plaqué sur du vivant]. Following Bergson’s theory, perhaps the underlying humor of the rod puppet resides in how it unites the image of man and machine, imposing human qualities on a machine, and vice versa. The sense of amusement is always a mental operation, a lightening-fast movement in the consciousness of the spectator. It doesn’t really make sense to speak of the comical “in itself”, though Bergson observes that the locus of the comic effect is very often a person or the human form, in particular one that reminds us of a machine or material thing. Just as we are amused by the absentmindedness of a comic character who is ignorant of himself or his surroundings, so too the automatism of the puppet evokes a certain mirth. Here, the artificial mechanization of the human body may equally be seen as the expression of a rigid mind or character. Therein lies the humor of dictators saluting to crowds, indeed of all ceremonial behavior where we find a “stiffness of mechanism” [raideur du mécanique] in place of the fluid and vital disorder of social life. Could it be said that Baby Marx also trades on this, by poking fun at the stiff, inflexible, or putatively dogmatic qualities of the old political Left? Isn’t there something comical about the utopian impulse itself? On this point Reyes is more ambiguous, for it seems that the humor is in fact directed, it is a way to engage us in a more serious reflection.

Where the thinkers of the liberal and market utopias have today reached a glaring impasse, architects and artists continue to explore the social imaginary. Partaking of the architectural imaginary, Reyes is evidently interested in the power of the artwork not merely to evoke new forms of experience but to create imaginary topoi, alternate worlds or epochs. In a sense, Baby Marx seems to propose the same principle. Here, history is shown as the motor of dialectical awakening, and the artwork as a time machine. Reyes’ revivification of the Old Left may be steeped in irony, but it is perhaps equally a form of Benjamin’s infamous “tiger’s leap into the past”. Finally, we might ask ourselves whether the comic dimensions of Baby Marx have a stronger effect of trivializing their subject, or whether, in fact they also work to re-invest it with greater meaning in our supposedly post-ideological present.

M. Downing Roberts

M. Downing Roberts