Photographing the Fallen Sky

Born in 1959, Naoya Hatakeyama is one of Japan’s leading contemporary photographers. Earlier this year, he held a solo exhibition of his new work ‘Ciel Tombé’ at Taka Ishii Gallery, and he is currently showing works in the “Heavy Light: Recent Photography and Video from Japan” exhibition being at the International Center of Photography in New York until September 7.

What led you to start taking photos?

That was simple. I was studying design at university, where I met a person called Kiyoshi Ootsuji. I found his photography interesting, and that’s what led me to start studying photography. Once I started studying, I found it more and more interesting and have kept at it ever since.

Looking at your work, it is clear from several of your series, ‘Blast’, ‘Lime Hills’, ‘Underground’ and now ‘Ciel Tombé’, that you have a fascination with the earth and underground spaces. What started this fascination?

One thing is that I like it. Well, it’s a kind of preference. When it comes to the inherent qualities of things, I like things that are hard rather than soft. My interest in photographing rocks and the earth is not so much about concepts as it is about this kind of preference that I have within me for things that have hardness to them: rocks, metal, things that are prickly. I start out with that kind of simple feeling, but then the quarries and lime hills that I have photographed all relate to personal stories of mine. It starts from the kind of place I was born, and from then it’s become a bigger and bigger issue. I realized that the lime hills that have recurred in my work have a unique character to Japan and have been valued for a long time. I was living in Tokyo and my perception of the city started to change as a result. And that theme has recurred in my work ever since.

These series all revolve around the same core themes, but articulate them in different ways. The ‘Blast’ works are overt and spectacular, whereas the ‘Lime Hills’ images dwell on the man’s slow, selfish chipping away at the earth, and yet the mood is gentle. The ‘Ciel Tombé’ works show both the result of man’s excavation and the force of gravity itself. How conscious are you of the differences in each series as you make them?

I’m not entirely sure what my final aim is, but when I think about my work, I feel that I want to increase the visual vocabulary. I’m getting to the point in my life where I want to shore up what I have achieved so far. So once I have enriched that vocabulary to the best of my abilities, I’m looking forward to seeing how it all works out as a whole.

How do you see this visual vocabulary relating to spoken and written language?

Words and images are intimately connected. People look at photographs and all kinds of words come to their minds, they find themselves creating a narrative and creating meaning. So I want to focus on things that, as far as possible, are fresh and haven’t been seen before.

I think that words are the basis of all things. This is a bit of a diversion, but photography in Japan in the 1980s was very anti-literature. To tell someone that their work was “literary” was the worst possible insult you could make. When I started studying photography, people who were about ten years older than me were using the word “literary” in a really bad way. It’s hard to believe it now, but that’s how it was. There are still some traces of that attitude today. Some people say, without giving it any thought, that they take photographs because they are bad at expressing themselves in words. I want to know what the reasoning behind that thought is. I suspect it’s probably a linguistic one. Linguistic structure suppresses those very words. It’s those structures that I’m interested in.

So to come to the new series ‘Ciel Tombé’ [French for ‘Fallen Sky’], can you explain how you came to choose Paris and find those underground spaces?

Firstly, when I was taking the ‘Lime Hills’ photos during the 1980s and ’90s, I already knew that there were these ancient quarries under Paris, and I thought that one day I would like to depict them in my work. During the 18th century, when Paris was undergoing urban redevelopment, bones that were being left on the streets needed to be cleared away, but you can’t just throw away some four to eight million bones. So they were stored in the old quarry spaces underground.

The catacombs are now a tourist spot; you can see them if you pay money to go and so I went. At that time I heard from a friend about people known as “cataphiles”. There are a few small entrances here and there around the city which have been blocked up, and the cataphiles open these up and go down into the underground spaces to hold parties and start campfires. But I didn’t feel that I wanted to go creep down there and take those kinds of photos. Then I came back to Tokyo and started the ‘Underground’ series.

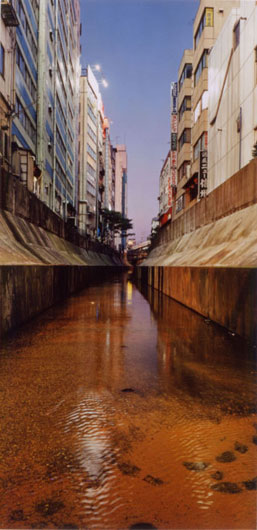

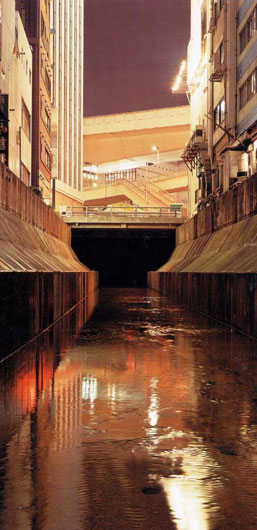

In Paris I remembered this photo [from the ‘River Series’]. When I took this one, I never went to the end. That was in around 1994. I thought of this photo when I was in the Paris catacombs and so I went back to Shibuya, entered that tunnel and made the ‘Underground’ series. But I had had the idea about the Paris underground before this.

‘Underground’ and ‘Ciel Tombé’ have slightly different subject matter, but essentially ‘Ciel Tombé’ is about gravity. In 2006 Michel Pinçon gave a talk on history and society at the Franco-Japanese Institute in Iidabashi. I talked to him afterwards and when I told him about my interest in the underground quarries in Paris, it turned out that he knew someone connected to them and could put me in touch, so it started from there.

Firstly I saw the quarries under Montparnasse Denfert, but wanted to find somewhere a little bigger. I was then shown told that there were bigger caverns but they had collapsed ceilings, and it was at that point that I learned they were called ‘Ciel Tombé’. I thought it was such a strange expression and I asked to see more. I found out that there were some caverns under the Bois de Vincennes, about ten of them. When I asked if there were any more, I was told that all the others had already been repaired. The character of this work was decided as soon as I heard the words ‘Ciel Tombé’.

How did you light the spaces?

I used ARRI lights, designed for cinematography. They’re square and they open up wide, and they have a lens inside. I borrowed those from a rental shop in Paris. I then found an assistant in Paris who would carry the light on the end of its cable for me, which made it possible for me to tell him from a distance whether I wanted it the light positioned a little more this way or that way. As for what I was looking to photograph in this series, it was the forms of these fallen rocks, so it was very hard to get the lighting right. I tried all kinds of set ups, but found that taking pictures with soft lighting that was being rebounded off the ceiling got the best results. So I would aim the lamp directly at the ceiling, and the light would rebound and give a soft illumination to the setting. In most cases, I hid the lamp from view within the photos, so that it wouldn’t be all that clear where the light source was coming from.

In some of them it looks almost like there is a hole in the ceiling going through to the surface.

Yes, there are some works in which it looks like there’s a hole in the ceiling and sunlight is coming through, but there are no holes. It’s just that when you point the lamp up at the ceiling, it reflects back white. There is one work in which the ceiling opens up like a chrysanthemum, and the middle of it is completely white. That one was produced by putting the lamp as far below as possible and pointing it directly upwards.

The ‘Ciel Tombé’ series, like all of your work, is an illustration of what people have excavated in order to build or service the city above, but even when you depict the inhabited urban environment, people hardly ever appear in your work. The overall impression is that you are focusing on the idea of cities as structures rather than as habitats.

It’s not that people never feature in my photographs; they do occasionally. The main reason for this is simply that I photograph places where there happen not to be any people, such as the rivers running through Shibuya and so on. I’ve also photographed the city from high places, such as the viewing decks in skyscrapers, so although there are people in those photographs, you can barely see them.

The second reason is, at least speaking for myself, that if you want to take pictures of people, you really have to approach it with that in mind. I just don’t really think of taking photos of people.

I don’t think of the city as a physical structure, but rather as the inherent product of people’s lives. So the question of how to photograph people is still a mystery to me. When I think about what the essence of the city is to me, it’s somewhere in those instants like the door of a subway train opening, or being in a convenience store and opening up a copy of Pia magazine. It’s at those instants that I feel the city. And those instants are hard to visualize. Many photographers would try to represent the city through people by going to busy stations like Shinjuku and Ikebukuro and photographing the crowds, but I don’t particularly feel anything when I see those kinds of photos. So if I were to start photographing people I wonder how I would do it. It’s a big question. But having photographed Tokyo from high places for some twenty years, I’ve seen the changes. In that sense you feel the effect of people, in terms of their activity. In that sense, you can perceive the city as a habitat.

How have your perceptions of Tokyo changed in those twenty years that you have been photographing the city from tall buildings?

For a start, the way the buildings are made has changed. So it’s harder to take photos now. It’s hard to continue to make that kind of work. Now, a number of skyscrapers that were planned during Japan’s bubble years are being built. They’re still building them. More and more finely detailed buildings are emerging in the center of the city. The skyline of Tokyo itself has changed. Then, with the exception of the work of some architects, some of these tall buildings have a very administrative, managerial aura to them. The world has come to worry more about how things are going to turn out. I feel that’s the mood of our time.

What do you think this feeling of anxiety stems from? Is it an anxiety about destruction of the city, for example, the expectation of a major earthquake?

Destruction is something that Japanese people feel is close to them. But people in Tokyo don’t think about the fact that a huge earthquake might happen tomorrow. I’m one of a lot of people who are optimistic and don’t really think about it. For example, there are a lot of people who get on planes with this belief that even if the plane crashes they will somehow be the one to survive, right? So I don’t think many people in Japan think about earthquakes or natural disasters. Of course, when Europeans come to Tokyo and there’s an earthquake the next day they get a real shock, but Japanese people feel this all the time, so they don’t have such a sense of psychological anxiety about it. Rather it’s people that they feel uncertain about. They are very sensitive to the anxiety they get from others around them. I’ve felt that really strongly over the last ten years.

How many people do you think there are who think about the Kanto Earthquake or the firebombing?

I couldn’t say. But I think that the events of September 11, 2001 have been instrumental in making people in industrialized countries, which have not seen acts of war committed on their own territories for some sixty years, realize that the city is by no means an immutable, invincible entity. The real trauma of that day was the loss of human life, but I think that the catastrophic destruction of the World Trade Center also sent out a profound and shocking message to world about the vulnerability of the built environment. So I wondered if your work is in any way a meditation on that vulnerability.

I’m asked that question a lot. I take the photos I want to take and people take my subject matter to be very exaggerated or tragic, but this subject matter is actually not such a big deal. For example, take the ‘Blast’ series. Those photos depict explosions, but the explosions are the product of labor that is taking place every day. However, having photographed those explosions from nearby, they come across as exaggerated images. I had been taking those photos for ten years, but after 9/11 there was a change in the way those blast images were perceived. Nobody thought of those blasts in a negative manner until then, but people’s interpretation of them changed after 9/11. That came as a shock to me.

Has that change in perception affected the approach you take to making your work?

I think that event brought up huge political and cultural problems, but as a photographer I have not thought of committing myself to those issues in my work. So I think about those issues as an everyday person. It’s possible that my photographs of explosions or of buildings due for demolition are somehow a presage of the death of the city, but I think I would be taking those photos anyway, regardless of the global mood. I didn’t feel any compulsion after 9/11 to change my way of thinking about my work. But that’s not to say that I was ignoring the implications of that event. I sometimes read that some artists were very affected by it, but that wasn’t the case for me.

How do you feel about the changes in photography over the past couple of decades?

The quality of viewers has changed. I think that’s the biggest thing. So I no longer make work with viewers in mind. There was a time, when I was younger, when I thought I could achieve something that would cater to a large number of people but I’ve had to give up on that idea. So now I just make work that balances what I feel I want to make with what I feel I can respect. So it’s a bit of a lonely situation, actually.

The last decade has seen a huge proliferation in photography. The borderline between professional and amateur photography has been blurred and together with the surge in international travel, the world has been very thoroughly documented in photography. The age of the photographic explorer as a form of pioneer is largely gone. It seemed possible to me that this past idea of revealing a “final frontier” or hidden spaces in the world might have played a part in making the ‘Ciel Tombé’ series. Where do you situate art photography in the current state of photography as a whole?

The kind of photography you’re describing is photography at its “informative” level; its subject matter and its presentation are implicitly informative. Of course, almost everything has been photographed. But photography has other levels to it. There’s the “graphic” level; there’s the “emotional” level, and there’s also the “intimate” level. Nobody can say that these levels of photography have been fully explored; they just haven’t. I think that the photographer is deeply connected to these four levels, but it’s possible that many photographers are losing their awareness of them.

In Tokyo the audience finds this kind of informative photography tedious, so viewers might not be able to lose themselves in the work. They are fairly indifferent to graphically appealing photographs, and emotionally appealing photographs are common too, so they are not that interested in them either. It’s only in these realms that people can make judgments about whether a photograph is good or not. And I don’t think that everything has been done in these realms, either, so I think people will continue to take photographs. It’s simply that the way photography is used in society has changed.

I’ve had some interesting reactions to my work sometimes. When I was making this book [A Bird], someone told me they thought these photos depicted things in this world that have never been photographed before. Personally, I don’t think of myself as being able to take a photo of that kind once a month; perhaps once a year or once in every five years. But when I do manage to take a photo like that, I feel glad to have been taking photographs for twenty years. This is not a problem of interior space, but a question of finding some kind of photographic pleasure in the image. So I’m really happy when I’ve taken a new, fresh photograph, but it’s a real problem when I can’t reuse it in my work somehow. So I don’t think that everything has been photographed. At this level, I really feel that not everything has been done yet.

And yet people believe that everything has been done. I’m a little suspicious of that. It’s unclear to me why people would think that. It may seem that way, but I don’t think it is, although it’s hard to say for sure exactly what the state is. Compared to the 19th Century, we’re in a completely different level of documentation now.

As for whether I’m some kind of explorer or not, I’m not that interested in photographers who say they take their pictures to document interior space. “Interior space” is a concept of the self. In Japanese, this idea of the “interior space” has a sense of this warm, fuzzy feeling of beauty inside, whereas this “self concept” is something you give to yourself, so it’s self-completing. As a photographer, I don’t think it is interesting to take that kind of thing as your theme. On top of cultivating the interior space, I pay more attention to the exterior world. So as much as possible I focus on the outside world. If I see that there is something we have not yet seen or something we do not know yet, then that’s what I want to address.

(Translation by Ashley Rawlings)

Ashley Rawlings

Ashley Rawlings