The Cultivation of Space

Under the title “Roof Garden”, the proposition of this exhibition sounded quite promising, in my mind I already conjured images of an exciting, innovative exhibition that explores the conventions of space and art production through some kind of dynamic contrived ‘garden’ space, thus redefining our perceptions of gallery art. The press release rather tantalizingly suggests that it will, “transform the sunlit third floor gallery into a sunlit roof garden”. In reality however it is quite an orthodox exhibition which displays a “spectrum of garden concepts” in artists’ individual work as oppose to any real spatial exploration. As for the promise of sunlight, the space was in fact lit almost entirely with artificial lighting, bar a few skylights that happened to be there.

Divided into ten sections, or ten “gardens”, the show brings together a diverse collection of work whose relation to the overall garden theme is at times somewhat tenuous. With titles like “The Evening Garden” , “The Documented garden” or “The Garden that Reaches for the Sky”, it gradually becomes apparent that the interpretation of the “garden” in art can be described to encompass, well… almost anything. Nevertheless, such versatility is also the exhibition’s strength, and visitors can encounter work in a diverse range of media from all over the globe, from the early Taisho period through to the present day. The artists featured make for an engaging group show, but at times the juxtaposition of twentieth century icons like Matisse with comparatively obscure artists of today gives the exhibition a disjointed or awkward feel.

The first gallery, the “Grotesque Garden”, is a dimly lit room, with its walls covered in a hand-painted black and white pattern of columns, rosettes and vines — reminiscent of a rococo-style hall. On closer inspection, gargoyles, pop culture characters and cog-driven machinery lurch out. This well tended garden’s absorbing ambience seemed to promise more spatial curiosities, however, what followed was a sobering return to a more conservative gallery space.

This second room, consisting of ink works and watercolours by Michisei Kono (1895-1950), includes framed images depicting rural landscapes, pussy willows and finely rendered studies of oak leaves. The following two sections, titled “Garden of the Studio” and “Garden in the Palm of the Hand”, featured works from the late Meiji, through the Taisho into the early Showa period. Of particular historical worth are works by the Taisho period oil painter, Torao Makino, and a series of magazine issues featuring prints related to the Shin Hanga movement of the early 20th Century that had revitalized wood-block printing and ukiyo-e painting traditions.

The “Evening Garden” and the “Enclosed Garden”, covering the period from 1940 to 1950, continued a more literal approach to the garden theme. Here, with the various works in oil, pencil and woodcut by Makino and a series of illustrative lithographs by Henri Matisse, references to nature, plant life and floral themes are featured prominently.

The last four “gardens” showcase contemporary works spanning the last thirty years. The first thing one notices is the disproportionately large number of works by Tadayoshi Nakabayashi — a veritable miniature retrospective in itself. Nevertheless, his work does fit well with the room’s concept of a “Documented Garden”. A series of fascinating semi-abstract, largely colourless aquatint etchings depicting dead leaves, twigs and other fallen, decaying matter make for a truly engaging display.

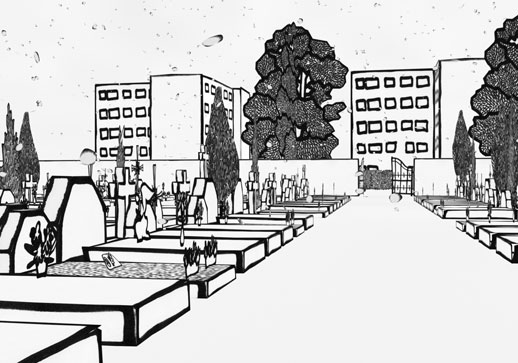

The exhibition then took an interesting turn with Benoit Broisat’s ghostly computer animated video projection Bonneville. Bonneville presents a series of silent 3D animations set in a snowy, deserted European castle town where the buildings, seemingly constructed of paper, sway and concertina to create an eerie, passive dystopia.

The ensuing display of abstract, neo-pointillist work by Satoshi Uchiumi demands attention. His bright and airy but meticulous and well-worked paintings beautifully coalesce with the garden concept, it is no wonder they feature prominently in the exhibition’s promotional material. His large green tinted canvas titled Below Colours conveys the feeling of being in the shelter of a great tree, whilst his whimsical but intensively constructed Great Chilio Cosmos is a universe in itself, composed of hundreds of small square allotments of colour.

In the end the strength of this exhibition seemed to reside in the way that each section represented a different approach to productivity and aesthetics in art, whether in a traditional, modern or contemporary sense. More particularly, it reveals how concepts of space, form and beauty can be ever-changing and transient. In the work alone I didn’t feel the garden theme was necessarily that apparent but what was apparent was perhaps that it was a meditation on utopia or paradise; the binding element that unfies all the participating artists is their desire to cultivate their respective visions, be it actual or metaphysical. Every piece of work represents the artists’ attempts to place themselves in a context with their environment, either through their own intervention or invention. Such acts are in essence the nature of the creative spirit and the human desire to carve out its own Eden.

Andrew Woodman

Andrew Woodman