Winning is Everything?

My first experience of the Turner Prize was at the Southampton City Art Gallery in the UK in 1996. The work of the four nominated artists was being showcased around the country, and I found myself glued to a Channel 4 documentary that explained the works, together with interviews with the artists that elicited justification for what they do. Watching Douglas Gordon shaving the hair off one of his arms in his video A Divided Self1, (1996) and listening to Simon Patterson justifying his version of the London tube map The Great Bear2, (1992) was intriguing. However, with work of this kind being nominated for the country’s most public art award it was always going to be contentious. In its defence, Janet Street-Porter wrote: “The Turner Prize and Becks Futures [another significant award] both entice thousands of young people into art galleries for the first time every year”3 and I for one am inclined to agree with her. At the age of seventeen it was inspiring and motivating to see these works.

Nonetheless, the beef that filled that Channel 4 feature of 1996, and every other documentary about the yearly competition since then, is actually the biggest absence at the Mori Art Museum’s latest survey show “History in the Making: A Retrospective of the Turner Prize”. Having been organized by the Tate and previously exhibited at Tate Britain in 2007, indeed, this is the first time that all of the award winners have been put together in one show. However, this exhibition is not a faithful representation of what the Turner Prize itself consists of. Where is the context in which the prize is set: the controversy it elicits among the British public? Where are the protests and demonstrations of the “Stuckists”4 or the outraged headlines of the tabloid newspapers demanding to know “Is this art?” Annoying as these bi-products of the Turner Prize are, an exhibition without them seems eerily quiet as though there are no more Davids to fight this Goliath.

There will inevitably be those who dispute each year’s eventual winner no matter what. In fact, in recent years, the Tate has made great efforts to gather people’s opinions at the end of every exhibition and obtain feedback on the judges’ decisions, a measure taken in response to criticisms of elitism and there being little effort made to involve the public. Nevertheless, the impact of that feedback has yet to be seen. If anything, it has only kept the public brawl alive, which is more than likely what the organizers wanted.5 As noted in some reviews of its London unveiling last year, this “retrospective” lacked bite and felt more like shrouding oneself in a warm blanket of familiarity. Although it was pleasant to see Damien Hirst’s Mother and Child Divided (1993) again, the kind of agitation that was expressed toward it at the Royal Academy’s “Sensation” exhibition in 1997 is long gone. To the British public, I would imagine this show had a certain “I told you so” after-taste to it, but bringing it here, to a country less familiar with the Turner Prize, frames the show more as an introductory course to British contemporary art — one that will no doubt raise Japanese interest in the participating artists. The director of the Mori Art Museum, Fumio Nanjo, who was also on the judging panel of the 1998 prize, has created a rather golden opportunity for the likes of Tomma Abts’ appropriately Japanese-apartment-sized abstract paintings with German first names, or Grayson Perry’s “technically accomplished” pottery, and I wouldn’t be surprised to see their names pop up a little more often in Tokyo from now on.

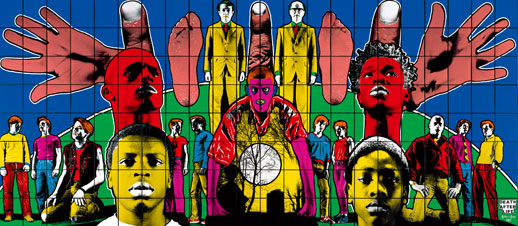

The Saatchi Gallery, London

The Saatchi Gallery, LondonWhile I don’t tend to care a great deal about who eventually walks away with the Turner Prize, its greatest success is in its ability to provoke a reaction and generate an opinion. The works picked every year may not be pretty or easily acceptable at times but the show as a whole does cast a light — albeit a very specifically directed one, given the actual breadth of the British art world — on a level of British Art that could be achievable by anyone. It is thus ironic that this exhibition at the Mori is quite ruthless in whom it excludes. Although some glimpses of the other nominees can be seen on monitors around the exhibition spaces, it might have been more interesting had this show actually included work by some of the arguably more interesting artists who didn’t win, such as Tacita Dean, Tomoko Takahashi, Simon Patterson, Darren Almond and even Tracey Emin. Without them, this exhibition affirms the sense that the winner takes all, far more than is actually the case, thus reinforcing the elitist air of which the prize has been so often accused in the past.

All in all, this exhibition stands as a rather oblique overview of the infamous prize and as a highly “filtered” survey of British art of the last twenty years. To a Japanese audience however, it is a worthwhile introduction nonetheless and one can only hope that it will inspire and motivate this audience to dig a little deeper as this writer did twelve years ago.

—

1 Not exhibited in this show.

2 Not exhibited in this show.

3 Street Porter, J.(2006) “Paul is better off without Heather”, The Independent. http://www.independent.co.uk/opinion/commentators/janet-street-porter/janet-streetporter-paul-is-better-off-without-heather-478626.html [Accessed 4th May 2008]

4 The Stuckists have been responsible for demonstrations outside and in the Tate Gallery since 2000. For further information see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stuckist_demonstrations [Accessed 4th May, 2008]

5 As comments were encouraged, Kim Howells, the then-Culture Minister, left a comment describing the works as “cold, mechanical conceptual bullshit”. Nonetheless, this reached the front page of the newspapers. Tate (2007) Turner Prize: A Retrospective 1984-2006, Tate Exhibition Guide, http://www.tate.org.uk/britain/exhibitions/turnerprizeretrospective/exhibitionguide/02-05.shtm [Accessed 4th May 2008]

Gary McLeod

Gary McLeod