Opiate Narratives

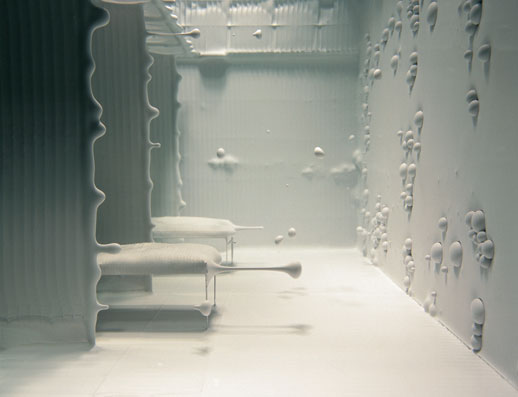

As I sit in a darkened room I hear the voice of a woman lying in her hospital bed. She is comatose. She lies next to her lover who, like her is holding onto the last strands of his life and the fictitious one he has constructed. The narrator cannot be seen: it is her voice alone that beckons you into her unconsciousness universe. As she spins her convoluted tale of deceit and disaster — a folorn story of a lover who assumes a false identity as a doctor — the story seems disjointed and delicate. The setting is equally frangible: a hospital scene constructed of meticulously wrought wire frames from which a white, glutinous paint-like substance bubbles and drips in all directions — a melting world of ward corridors and operating theaters. It all seems so tragic, and yet so very beautiful. Everything in Wolbers’ world is fragmentary, like a dream. The fantasy is utterly absorbing until the end when suddenly the scene melts away, leaving just a hollow frame, and plunging us back into reality.

This is Placebo, one of two works by Saskia Olde Wolbers being featured as the ninth in a series of projects held at the Mori Art Museum with the aim of promoting young promising artists. Located at the end of the current Turner prize retrospective. Placebo is one of her most well known works, its style indicative of her oeuvre. Her videos are instantaneously hypnotic, a combination of surreal, winding narrative and alien, dream-like backdrops. She constructs these settings from an array of props and found objects, and their execution is so impeccable that they can easily be mistaken for computer-generated imagery.

The second work, Kilowatt Dynasty starts with the voice of a young Chinese girl, speaking in broken English. “Let’s try to imagine that I am going to born in seventeen years”, she says, perplexingly. Although her works immerse you in a sense of wonderment, Wolbers often starts by constructing her fantasies around actual news stories and oracular anecdotes. Set in a future China after the completion of the Three Gorges dam, Kilowatt Dynasty takes us into a space-age fantasy world of underwater towns and hi-tech television shows. The opium-like mood of Wolbers’ work draws you into a sense of intimacy with the faceless narrator, who tells us how her parents are to meet in seventeen years’ time — the story centres on her mother, a TV celebrity, as the object her activist father’s failed kidnap attempt. This rather bewildering chronicle tragically concludes with the her mother finally succumbing to inverted dream-states, unable to tell the difference between dream-time and waking life.

Wolbers is also showing at Ota Fine Arts, which recently relocated from the Roppongi Complex (closed in February) to a modest two-room space tucked away on the fourth floor of a nondescript building in Kachidoki. Here, a single video work titled Deadline is on display. The narrative is told from the perspective of a young girl who, together with her father, undertakes a long but fruitless odyssey across West Africa, from Gambia to Nigeria to reunite her father with his twin brother. As the story unfolds, snake-like forms slowly traverse the screen, intermixed with shots of small, curved stone blocks, broken and piled-up like modernist architecture, structures that are redolent of the dichotomy between the realities of African life and the grandiose municipal architecture and expensive hotel show pieces that can be found in West African capitals like Lagos and Monrovia.

This layered tale of deception and disappointment leads you down a muddied path of lucid fantasy, a bush-taxi trail of half-truths and scattered dreams. However, unlike the works on show at Mori, the narrative in this work invokes a stronger sense of realism. The exhibition at Ota Fine Arts features documentary photographs that Saskia Olde Wolbers took on a trip to West Africa, many of which seem to have a narrative that runs parallel to that of her video piece, lending the realism of her story an almost unsettling weight. Hardship in Africa, in whatever form it may take, is the staple of the contemporary news media and the first point of reference for many Western viewers. With this in mind, Olbers’ work seems to bear the fruit of a deeper connection with her subject matter. As opposed to being made from the latest news vignettes, the story has a more organic feel, with relation to Africa’s own folklore and oral traditions.

Andrew Woodman

Andrew Woodman