Portraits of the Underworld

Katsumi Watanabe is the definitive photographer of Tokyo street life, known for his four decades of relentless focus on the hustle and bustle of Tokyo’s Shinjuku district. With a background as a photojournalist, Watanabe became a familiar face along the seedy side streets of Kabukicho and in effect gained insider status and behind-the-scenes access to many of the neighborhood’s forlorn storefronts and clubs. The Watari Museum’s current posthumous exhibit of a portion of Watanabe’s archives (easily over thousands of photos) serves as an authoritative, if unofficial history of the extremities of Tokyo’s social and cultural life.

Roughly separated into decades by the museum’s three floors (1965 to 1977, 1978 to 1989 and 1990 to 2005), Watanabe’s earlier photographs center on the liveliness of Kabukicho’s cradle of back streets, Golden Gai (Golden Street). Here, Watanabe documented the tin-pan alley side of Tokyo, snapping the busking street musicians who provided the soundtrack to a nocturnal lifestyle that comprised of both hedonism and despair.

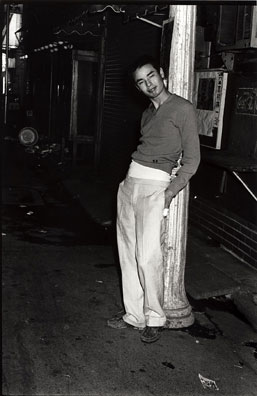

As a portrait photographer, Watanabe’s narrative approach focused less on the development of individual characters caught up in the city and more on the lifestyle engendered by the area itself. Personal narrative or character development in individual citizens is subsumed by the hectic character of Shinjuku itself.

The success of Watanabe’s priceless, candid moments at street level is matched by his investigation of life behind the scenes, including the so-called ‘Turkish’ baths and brothels or the backstage scenarios of nude clubs nestled in Golden Gai’s side streets. In these enclosed, hidden environments, Watanabe was able to connect more intimately with his subjects, with perhaps more flexibility to push them for poses or retakes — and as a result, this side of his portraiture excels. Whether backstage at a club focusing on a trafficked sex worker or surveying the dismal living quarters of the homeless throughout Shinjuku, these photos are profoundly more personal. These images compel you to consider the uncertain histories behind each of his subjects; you might find yourself wondering where they might be now or if you even encountered them on the streets already. Watanabe had an uncanny ability to never miss a step on candid shots, clearly finding himself at the right place at the right time, again and again: darker images of crime scenes, corpses covered in white blankets and the occasional fist fight are just as thought-provoking as his portraits.

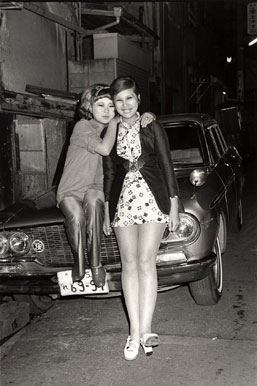

At the same time, Watanabe did not just focus on the dark and seedy but also turned his lens towards the scenes of glee and joy. The exhibition features many images of bar and brothel staff, women with merry smiles working in clubs, men in drag, women in negligee standing on the street, rock ’n’ rollers with their signature pompadour hair styles, bikers, as well as women in their 1960s mod dresses and bob-style hair cuts. Into the 1980s, the playful shots of women smiling and posing in front of cars, the ink-drenched yakuza or the emergent pompadour or mohawk-strutting punk rockers in underground clubs are a series of tough poses and tight lips — Watanabe’s subjects convey the confidence all too synonymous with the nation’s booming economic times.

Watanabe’s work from the 1990s and recent years focused on the younger crowd, signaling that while not much has changed since then, the cultural processes at work have merely accelerated. The youthful subjects, sitting curbside, only seem to get younger and younger the further you progress into the 1990s and 2000s. More recent subcultures slowly emerged to the fore: goths, hip-hoppers, wannabe thugs and gangsters together with the more eccentric ladyboys and now infamous bleach-blonde, overly made-up ganguro garu. I’m tempted to say if Watanabe were still alive to shoot, his camera would most likely lead him to the bling, or so called “elegance,” that flickers throughout the contemporary pedestrian’s peripheral vision while walking around Tokyo.

Extensive as it was, Watanabe’s privy camera flash of insight into some of Tokyo’s darker corners reveals that not much has changed in Kabukicho. It is still just as sleazy and gritty, scattered with litter, and populated by homeless who are ignored. It still remains a place for porn scouts, it is still thought of as “dangerous” and patrolled by police who turn a blind eye to the prostitution all around them. But as every good exhibit should, Watanabe’s compendium of photographs raises questions about his subjects and Japanese contemporary society. Not just, “Who were these people?” but rather, “What were they living for?” or “What dreams were they chasing on the ‘Golden Street’?”

While a retrospective exhibition of photography that fills just about every inch of exhibition space can sound a little daunting, no two of Watanabe’s photos came across as the same. Every image fits into a mini-series that carries its own set of associations, be they cultural, social, sexual, hedonistic or just tragic.