Bauhaus Strikes a Domestic Chord

Walter Gropius, leader of the Bauhaus from 1919–1927, credited traditional Japanese architecture, à la Katsurarikyu, as an advanced form and justification of modernism. Now a collection of his school’s output resides in the archives of Misawa Homes, which established the Misawa Bauhaus Collection as a laboratory, research center and museum. This exhibition, “Bauhaus Housing & Furniture,” is the twentieth that Misawa Bauhaus Collection has staged and, although a mere sliver of the collection, is impressive and far-reaching.

The housing portion—i.e. architecture—presents sketches, drawings, prints, publications and newer representations including models and video. Most of the videos are computer renderings that highlight circulation and volume of select projects including Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion and Gropius’ Bauhaus Dessau building. Unfortunately none are particularly analytic. By moving through rather quickly and jarringly, they forego revealing geometric or formal relations. Two exceptions follow. One, the ADGB Bundeschule, juxtaposes black and white stills with recent color video, somewhat jerkily, to clarify that the ‘minimal’ abstracted visions weren’t always monochromatically neutral but colorfully rich. Also, Hannes Meyer’s Peterschule reveals somewhat more technical and structural characteristics that suggest an influence on some contemporary cantilevers and circulation.

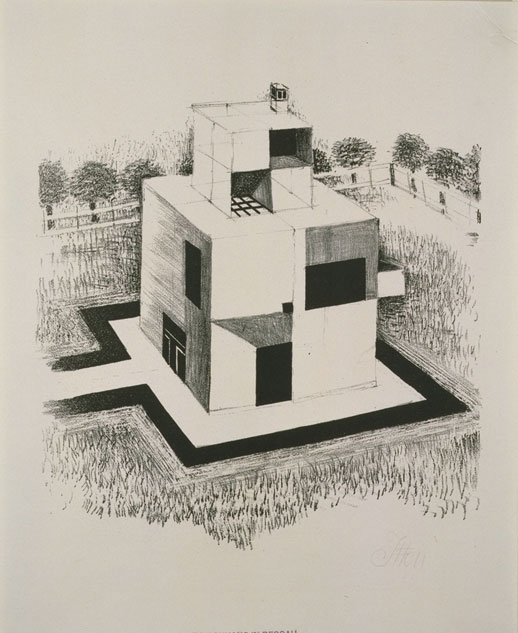

Karl Cieluszek’s precise hand-drawn pencil working drawings and studies—the envy of any architect—are beautiful in their simplistic composition and belie a contemplated consideration rarely revealed in CAD drawings. Drawings, photographs and models show various stages and interpretations of the Experimental House by Georg Muche (who is also represented by a few striking prints in the Collection’s impressive and extensive library), Adolf Meyer, Marcel Breuer, and a version as realized by Gropius in the Meisterhaus (1926).

It is through the latter two Bauhausers that the exhibition jumps to furniture, although mostly through Breuer who is represented by numerous pieces, including the ubër-comfortable and stylish bent steel and leather Club Armchair B, more commonly known as the ‘Wassily’ chair (1925). However the more interesting works on display are Breuer’s Wohnbedarf type 301 and 345 (1932–34), chair and chaise longue respectively. The frames, instead of bent tubular steel but just as elegant, are parallel pieces of bent aluminum bar stock that are more expressionist than their abstracted counterparts. Reminiscent of bent wood furniture, the grainy bent metal forms, rather than suggest a cool smooth naturalism, evoke a visceral strength. Erich Dieckmann furniture, Otto Rittweger lighting designs, two carpets and numerous other works round out the furniture portion of the exhibit.

That it is primarily in Japanese, although the expected German abounds, doesn’t hurt the exhibit as most of the didactic text places the material in a larger context, especially in the several meter-long time line that greets visitors. The fruit of the exhibit exists in the objects and artifacts themselves that show how the simple, refined and slick ‘contemporary’ design that currently feeds the ‘lifestyle’ market had its origins more than 60 years ago. It is a rare opportunity to see this variety and quantity of Bauhaus materials presented together. Although reservations are necessary (and easy to make – I did it with my fumbling Japanese), it would behoove anyone interested in architecture, furniture or design to visit the Misawa Bauhaus Collection at some time.

James Way

James Way