Curating from Outside Museums

Roger McDonald was born and brought up in Tokyo in 1971. He studied in the UK and returned to Tokyo in 2000 after completing his PhD. He is one of the six arts coordinators who founded Arts Initiative Tokyo (AIT), a Non Profit Organisation that operates as an independent art school, as well as curating exhibitons and organising a variety of events, lectures and artist residencies.

How did you set up AIT?

It was very informal. Out of the six of us who are the initial founding members, five have spent some time abroad studying contemporary art, art history or some other related subject and we all ended up back in Tokyo around 1999, 2000. We started getting to know one another at art openings, having informal discussions of what was lacking in Tokyo’s art scene, and at some stage we felt that we should actually initiate something rather than just talk about it.

We spent about six months trying to lay out a groundwork for what we could actually do to answer some of the questions we had about the art scene in Japan. During that time we did a lot of very basic research, talking to many people working in the art world – gallerists, curators and artists – about what they thought was lacking, what they thought might be needed.

Out of that emerged two primary things that we thought we could do. One was MAD (Make Art Different), which is a sort of contemporary art study program. The other was an artist in residence program, based in Tokyo. At that point, neither of these seemed to exist in any systematic way. There were artist in residencies being held in Tokyo before, but they were mostly organised on a very personal “just stay at my house” kind of basis; there was no official route for an artist from abroad to apply.

We felt that these two things were worth pursuing and in 2001 we started by opening MAD. About 12 people applied and we only had three courses to start with: a curating course, an audience course and an artist course. In 2002, we became a Non Profit Organisation.

What was the motivation for that?

This was something that we debated a lot. We could have become a limited company but we felt that again what was needed in Tokyo’s art world was a publicly accountable or publicly accessible art organisation rather than yet another company. The NPO laws at the time were changing so it was fairly easy to apply to the Tokyo city government and we got an interview within eight months; I hear it’s getting harder now, because there are a lot of unscrupulous groups that just use the term NPO to cover other things. But it’s a fairly rare structure to find in Japan anyway, and it has a lot of merit if it’s used in the right way. There are no financial or tax break benefits in becoming an NPO at the moment: the only benefit we see is in terms of social status; when we’re applying for funds from some foundation, it elicits a more friendly response.

With your MAD teaching course, which stands for ‘Make Art Different’, what are the aspects of art that you feel should be made different?

Talking specifically in terms of art education, art schools in Japan are failing to talk about the administration of art or the issue of how we talk about art; these topics are very much overshadowed by an emphasis on technique and formal approaches to art making. In most Japanese universities, departments are also very segregated; there is still only a very limited sense of interdisciplinarity. I think contemporary art by its nature necessitates a much broader approach, using different disciplines and borrowing from philosophy, so we felt it would be good to offer a discursive space where people who are just interested in these things can talk to each other. Public programs in museums have tended to focus on children more than adults, or take the approach of offering very simple guided gallery tours, and we thought that it would be more useful go a bit deeper and read theoretical texts as well as meeting with artists and other things.

How do you view the teacher-pupil relationship in Japan compared to anywhere else in the world?

At a very basic level, there is the fact that the pupils call their teacher ‘sensei’ (meaning ‘teacher’ or ‘sir’). I went through the British education system right through to my Ph.D, and during that time you meet many very respectable professors, but you call them by their first name. So at MAD, the first thing we say on orientation day is that the word ‘sensei’ is banned and students should call us by our first names. The older people are fine with it but some of the younger students are a little taken aback.

Other than that, there is the whole master-disciple model of teaching in Japanese art schools. I teach at Zokei University, Tama Art University and Musashino Art University, where I often do studio visits and this model still exists there; it is perhaps a residue of the traditions of Nihonga painting, but it is thinning out with the younger generation of teachers coming in. To put it another way, I would want my students to question what I talk about much more and not just accept it blindly. It’s often quite difficult to generate discussion, although we really try. One of MAD’s main points is to be a discursive space: we’re not interested in being teachers who do nothing but speak to the students without them having a chance to speak back.

What techniques do you use to get people engaged in discussion without them feeling put on the spot?

Often we do mini workshops, and in them we get people to break off into pairs or groups and think about a topic for ten minutes and then present back to us. We found that just by preparing some basic structured entry into dialogue, it really makes all the difference in Japan, whereas in my experience of doing a bit of teaching during my Ph.D in England, I found you don’t have to say anything at all and the students will be chatting endlessly. That emptiness here was really difficult to deal with at first.

Can you tell us about the residencies you organise?

We had this very strong impression that Tokyo is a destination that many artists feel they would come to, if only there were some kind of structure to receive them. There was a real need for residencies in Tokyo and we have been doing them for four years now. We like to think that Tokyo Wonder Site started their residency programmes partly a result of seeing the fruits of what we’ve done. Often in Japan, I think it’s fair to say, the city authorities will never initiate something by themselves and will wait to see how it works out in the private sector first. So in that sense, I think we’ve perhaps played an interesting role in taking a lead that the city of Tokyo has followed on from. And that’s great for us: the more residencies in Tokyo, the better.

To fund our residencies and invite people to Tokyo, we’ve had to form partnerships with foreign art institutions like IASPIS in Sweden and FRAME in Finland. It dawned on us that most of these organisations are from northern European, fairly wealthy, developed countries, and this spurred us to encourage South Asian artists or African artists to come to Tokyo. Over the last two years we’ve started to fundraise ourselves, from semi-private foundations based in Japan such as the Ishibashi Foundation, which runs the Bridgestone Museum of Art, and also from the Backers Foundation. Thanks to them, we’ve been able to broaden the range of artists that we can invite, so they are not necessarily from countries that have these funding structures in place. We’ve managed to invite artists from Palestine, the Philippines and Pakistan. It’s important for us to open up a channel for people who have fewer opportunities to come and work in Tokyo.

What do you ask the artists to do while they are in Tokyo?

With our residencies, unlike many, we give the artist no obligations. I know that for some residencies like ARCUS in Ibaraki, the artists have to do a lot of PR for the local council and so on. We say to our artists straight away that they are essentially free for three months and we are here to support them in any way we can; if they want to stay in their rooms and read all day long, that’s fine with us.

The one thing we do try to encourage is that they give at least one public talk or seminar that can tie in with our MAD school program. We don’t have an exhibition space, but we have a school, so we’re trying to develop a program in which the resident artist can maybe develop their own kind of special course on any topic that they’re interested in, which becomes a public course that anyone can take. This idea stems from the fact that artists are not only makers of a final artwork, but people full of incredible, fascinating knowledge and insight that carries them through that, which we would like to share in a school format.

Last year, Magnus Bartus from Sweden did a really interesting three-session seminar about art and patronage in North Korea and we looked at a film from North Korea called Pulgasari, a Godzilla rip-off made in the 1980s. Khadim Ali talked about the situation of being an artist in Pakistan and Afghanistan and the history of miniature painting in that region. Hopefully these kind of lectures give another take on what these artists are thinking about.

Can you tell us the ideas behind the 8 Hour Museum and 16 Hour Museum that AIT held at Hillside Terrace and Super Deluxe in March?

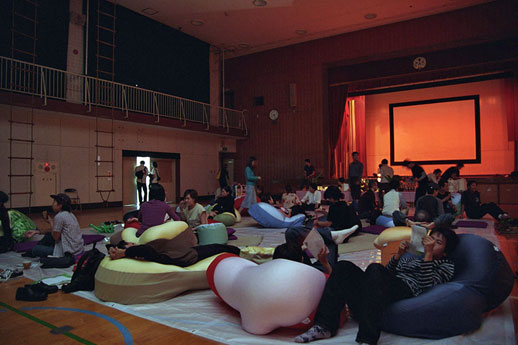

We held the first 8 Hour Museum in 2002, in a disused elementary school gymnasium and have organised several since then.

The idea stems from the fact that we don’t keep any kind of exhibition space. It’s too expensive in Tokyo to maintain a clean white cube that at times will stand empty for weeks on end. There are plenty of those already in town. The office where we work doubles up as a classroom in the evenings so it’s perfect for what we need it for, but being curators, once in a while we want to do something that involves artists and artwork.

The hour museum concept partly borrows from Archigram’s ideas about ‘plugging into’ a city and using pre-existing infrastructure in other ways. I think Tokyo is the perfect urban situation for that way of operating: it has a very dense population, it has an incredibly efficient public transport system which can get people from A to B quickly, unlike London. If we tried to do this in London… well, it would be ‘different’; maybe people could walk between places.

We try to think about the situations we’re in and ask ourselves what we can do that would be interesting. Recently, there has been a lot of development going on in Tokyo, with a lot of public space being privatized or semi-privatised. Indeed, how can we think about the idea of public space in Tokyo? I think there are differences from the Northern European approach, which would stem from philosophers like Jurgen Habermas. Where can an idea of a civil society emerge in Tokyo now? The city is, I feel, highly regulated and ordered by clear commercial interests, and yet within this there are always moments of difference, of something changing, moments which reveal normally hidden things.

We wanted to work within the city fabric and so these two issues led us to discussing the situation of museums and of art spaces in Japan at the last 16 Hour Museum. I think museums here are going through a real process of change, crisis even.

What kinds of changes are being made to museum laws?

Their funding from the state has been reduced considerably since 2000, with the aim of making them run their finances more independently, like museums in the United States. They now have to raise their money themselves, through all kinds of ways.

The funding of museums in Japan is now somewhere in between the European model, which is largely borne by the state, and the US, which is almost totally private. Obviously this has had a human cost: it has led to personnel changes, curatorial contracts changing from full-time to part-time, and I think it has negative implications for academic research in public museums and the status of archives and public collections.

There is some hope: the Ashiya Museum in Hyogo Prefecture was under threat of closure in 2004, but I understand that the local community rallied around it, formed an NPO and started a petition, which a lot of the international art world signed up to and it eventually helped forestall the closure.

However, on the other hand you have museums that have to concede their administration to open tender: essentially anyone can now write a proposal to run public institutions under three or four year contracts. There have been some interesting cases. I believe Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art did an open tender and one of the applications was from Yoshimoto Kogyo, the famous Osaka-based talent/comedian production company. Who knows what they would have done if they had won the bid; I can’t quite imagine what motivated a comic talent scout company to think they could run a contemporary art museum. It could have been interesting, but then again, the Hiroshima City Museum has an important collection of atom bomb art… so I’m not exactly disappointed that they didn’t get the bid.

So with all these changes going on over the past few years, it was the perfect time to introduce the idea of a museum that isn’t such a heavy physical presence. There are other ways to think of the idea of a museum.

Did you decide to keep the word ‘museum’ in 16 Hour Museum so as to emphasize your desire to redefine its meaning, rather than replace it altogether?

We very consciously wanted to keep it in the title just so as to remind people of the word. But hopefully the kind of experience you had if you did come to one of our ‘museums’ is very different physically and psychologically from what you get at the Mori Art Museum or Tokyo Opera City. We were also drawing on the very rich historical and artistic tradition of curators probing different experimental ways of showing art. I’m particularly interested in the curatorial history of art, and this is a sub-history within the history of museology that one has to be aware of. After all, I feel that exhibitions are essentially psychological visual experiences made up from very specific placements of objects and images. So I often discuss histories of architecture and interior or furniture design in my classes, as parallel disciplines which probe our relationships with space.

It struck me when I went to the second half of 16 Hour Museum at Super Deluxe that it took a little while to get used to the space. The fundamental difference between 16 Hour Museum and most regular museums was that it invited you to sit down and stay, rather than just channel you through a pre-decided exhibition route.

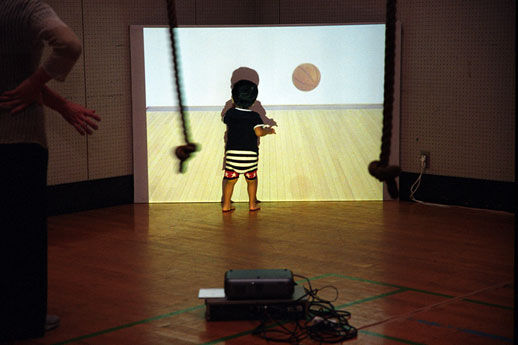

The experience changes according to the space we do it in. Super Deluxe is more of a black box with a club atmosphere, a bar and a DJ booth, and we had to tune the programming to fit that mood.We brought in some inflatable walls and performance was a key part of the experience: we produced the catalogue of the exhibition live during the evening. At others that we’ve done, such as the first half of 16 Hour Museum, held at Hillside Terrace in Daikanyama, we emphasized the discursive element with a series of lectures, and invited four speakers to talk about any topic they felt was important in this time. In Europe in the last few years there has been this debate about so-called ‘new institutionalism’, which is a discussion amongst museum professionals about how the museum as a structure and working model has changed since the 1990s and different kinds of art making have come into play.

The Mori Art Museum hosted a symposium in February that brought the directors of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Centre Pompidou, Tate Gallery, and Istanbul Modern to discuss the future of big museums. Of all of the panelists, I thought Nicholas Serota of the Tate was the progressive: he was the only one to go so far as to acknowledge that there will eventually come a time when museums can no longer adapt to serve the contemporary art situation of the period, and eventually something different will take their place.

Yes, that is a pretty remarkable thing for the director of the Tate to have said. There was a huge surge in the questioning of the museum during the 1960s, and artists were making very ephemeral works that could not be collected or shown very easily. Museums are a strange paradox, because they give an aura to anything and everything. In the Mori’s recent ‘All About Laughter’ show, the first room of the contemporary section was really interesting in that it had a lot of Sixties art from Hi Red Center and Fluxus, which was fairly ephemeral stuff, and yet it was all displayed in glass cases. It always baffles me whether or not we should really be seeing these things in these conditions.

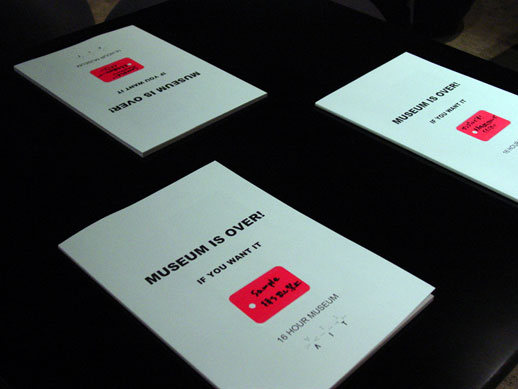

With regard to what Nicholas Serota said, the title of our magazine for 16 Hour Museum was ‘Museum Is Over, If You Want It!’ and that’s obviously taken from John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s work ‘War Is Over, If You Want It.’

But I don’t get the sense that you’re trying to subvert the museums, because you rely on museums to a certain degree to help you do what you want to do; what you’re doing is more about offering alternatives, providing what they are unable to provide.

That’s very true. Maybe that’s something specific to our generation: maybe in the Sixties and Seventies, artists and curators would have been much more oppositional to institutions, trying to burn them all down, but I’ve benefited greatly from museums and I love going to see their permanent collections. Serota recognizes that the form and presentation of art changes through time and the ways curatorial practice occurs has to change and shift along with that dynamism, and that’s what we’re responding to.

And what motivated you to introduce the element of time into the redefinition of what a museum could be?

We wanted to reintroduce the idea of ‘theatre’. The whole notion of the physical aspect of spaces comes up in particularly American criticism of the 1960s and 70s and I think that with Nicolas Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics and new media art practice – notions of theatre, performativity and activating audiences in some kind of way – is very much there today, so I would hope that museums can accommodate that in some way.

In the 1970s, Brian O’Doherty wrote something in his book Inside the White Cube that I have always liked: that from the white cube’s perspective, the ideal viewer of art would be just two eyeballs floating through a space, because the human body is such dirty, repellent thing; the moment we walk into a white space, we threaten to contaminate it.

Given all the problems that are thrown up by notions of physical space in the art world, it brings up the question of what future there is for art in virtual space and the internet. The internet has already done a lot for the art world, and yet most museums seem not to have harnessed its potential to further their own aims.

That’s true. Not that I want to sound like a spokesperson for the Tate, but their website is one that I refer to all the time for teaching purposes. It is the only large contemporary art museum I know of that has online video archive of its entire public programming, all its artist talks, all its lectures with eminent critics and curators for the last six years. There’s about 100 or so Quicktime videos that you can watch and that for me is a very good way of using the internet, especially when I can’t be in London more than once a year. It’s a great way of keeping in touch with what people are thinking about over in Europe and all the debates that are taking place there.

I also think that all museum directors should have a blog. Writing a blog strikes a good balance in between writing for a paper publication, which somehow makes you feel like you’re producing something finalized for eternity, and writing a personal diary. I feel that you can let things out more on a blog and that it’s a better medium for accommodating the fact that your opinions will evolve over time.

What do you think of art writing in Japan?

I find that most art writing here tends to be reportage and quite journalistic, although I’m probably as guilty of this as anyone else. You only really have ‘Intercommunication’ at ICC and a few other journals; on the whole, I find that there’s not that much writing which is trying to frame the art or subject in a broader art historical or critical framework and that’s something that needs to change if contemporary artists in Japan are to operate at a more international level. For instance, in China, there’s the magazine ‘Yishu’, which is published in Canada in English, but distributed worldwide and its focus is solely on Chinese contemporary art. I think ‘Yishu’ has a very high standard of writing. I often wish that there were such a magazine in Japan.

You write a blog called ‘Tactical Museum’ and you’ve referred to using ‘tactical curation’. What do you mean by ‘tactical’?

I’m trying to work out what it means to be a curator operating outside of any kind of large art institution. Neither I, nor my colleagues at AIT have ever worked at a gallery or a museum and I think it’s still a relatively young kind of mode of working for a curator. Some people say that Harold Szeeman was the first independent curator in the late Sixties, but particularly from the 1990s, all over the world you see people calling themselves freelance or independent curators and I am trying to probe and explore the unique characteristics that distinguish curators who work independently from those who work in an institution.

The word ‘tactical’ is borrowed from Michel de Certeau’s Practice of Everyday Life but also when I talk about this idea in classes, I refer to the US tactical military field manuals, which is something that I get inspiration from as a curator. It talks about camouflage and stealth, issues that I think are relevant to independent curators who don’t have many resources and who have to rely on existing things. You have to find your own situation, create your own situation, since you’re not necessarily given any kind of defined space.

Saying this though, recently I am also thinking about the importance of strategy – the flip side to the tactical. Without a strategic mind, tactics rarely evolve into something more meaningful or widespread. As de Certeau writes, I guess the key is about negotiating a balance between these two levels of operating. I hope that AIT has tried to always find this balance – this is perhaps also related to the issue of becoming institutional versus ‘alternative’. Can we suggest that it’s about knowing when to strike the right pose…?

How does the idea of stealth apply to the art world?

As I see it, currently most museums tend to be aiming for greater audience numbers and trying to attract people to their cafes and shops to buy things. I think this is necessary up to a point, but it also invites the question of what you lose by doing that. There must be things you gain, such as bigger audiences and more money, but there must be things you lose or become harder to do or impossible to do the more you follow that marketing strategy. A lot of contemporary art is fairly difficult or inaccessible, so curators have to ask themselves whether it is our job to make things easy and accessible, and if so, for what reason. I’m actually quite interested in the idea of there always existing a layer of quite dense exhibitions and projects that are not necessarily so accessible; I think they are necessary element of any healthy art scene.

It’s very easy to be dazzled by all the promotion that surrounds the big exhibitions. Is the idea with MAD that you’re aiming to provide people with the art historical context so that they can cut through the white noise and understand what they’re looking at?

I think so, otherwise how different are the museums to your local Jusco? That’s why a curator’s job is particularly important in this day and age: we need to find the balance between attaining large audiences and what the artists are originally thinking about, which is quite often not geared towards large audiences at all. A good curator is someone who can find the right words to convey these things, someone who can find the right psychological and physical ways of working with spaces to put across those difficult issues.

Ashley Rawlings

Ashley Rawlings