A Japanese Eden in a Darkened Warehouse

In a city that rebuilt itself fairly recently, and whose landscape is for the most part marooned in a mid-century taste for concrete and shiny acrylic textures, Gallery ef is a stubborn exception that wears its age gracefully. The frame of the building is muscular but delicate; cypress and pine timber columns form the skeleton of the warehouse, and the interstices are filled out with plaster. Entering and walking past the café out in front, you cross gingerly over the pebble-strewn threshold, stepping up into the back storehouse staggered with gloom. Joelle Bitton’s film and light installation, dappling the carpet in the center, is the only illumination in the dark room.

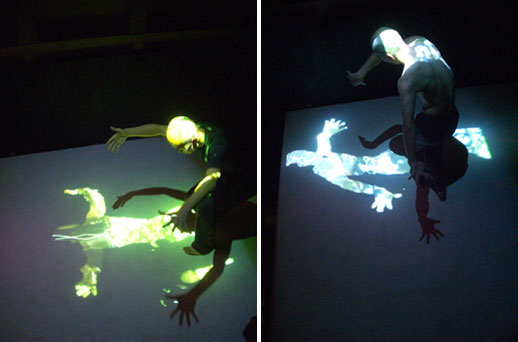

At first you aren’t quite sure how the projection works. Dipping into the line of sight of the projector hung overhead, you reveal the image instead of obscuring it; by passing underneath you expect to be disrupting the performance when in fact you are enabling it. On its own, the projector settles into broadcasting a void, streaked with light. When you enter into the field of the projector, greenery swims into view – there are sunbleached images of rock gardens, summery shrubs, placid backyard views from the edge of the engawa (Japanese verandah), fluttering leaves in the wind… It turns out that in fact there is a second device, a camera positioned on the floor at the far end of the room that captures your silhouette, whose shape is then transcribed and colored in with the projection. As the audience you very literally frame the event with your physical outline. While you explore the space of the installation, you materialize the “spirit” of the garden. Groping around the darkened interior of the warehouse, you are equally stumbling through the virtual televised space of an enchanted grove.

It’s a sort of pastoral psychogeography, an overexposed reel of life from an imaginary film – a film, however, of which you are only permitted to view as much as you dare. The experience is haptic and visionary, in a sort of prosaic way, because you illuminate the images only as far in as you dare to tread. Or rather, the more you get into it, trying desperately to reveal the entire scene, the more you realize how hemmed in you are by the darkness. There’s something compellingly embryonic about navigating the space of the carpet, something that’s enhanced by being barefoot and feeling your feet caressed by it, as well as being cradled and walled into the back of the warehouse with its exposed woodwork. That sense of a primeval return owes itself equally to the peculiar light quality of the camera work. The garden is an elsewhere but also very probably an ‘elsewhen’: the images have that saturation of white light from a lost childhood Super 8 video unearthed from a dusty basement, helping you to recapture a nostalgic tree-grove childhood you never had, or could never find.

And yet, once you’ve figured out how it works, you’re still just fumbling around, albeit “interactively”: Bitton has cleverly orchestrated the experience so that you are always limited by a setting that replays itself, to itself, infinitely: the experience is equal parts a time slip and a time bubble. You are transported, and yet you are also only suspended in this chamber where you enjoy an endless rerun of a false nostalgia. Like a Plato’s cave that televises a magical Japanese Eden into the darkened warehouse, Bitton’s installation also broadcasts an internal message: the interaction of the audience with itself, and with its own personal Arcadia trapped within each of us.

Darryl Jingwen Wee

Darryl Jingwen Wee