Vivo: Photography from 1960s Japan

The Shadai Gallery is a university gallery: basically a large room, with no windows and old spotlights in the basement of Tokyo Kogei University. But I went looking for photographs, not curatorial magic, and this seems to be one of Tokyo’s small, dedicated ‘photographers’ galleries. The six Vivo photographers; all bigger or smaller ‘VIPs’ of post-war Japanese photo-history, were each represented by eight original prints drawn from the gallery’s collection, and while many are familiar as individual series, this was a rare chance to see them exhibited together, as ‘Vivo’.

Vivo was a post-war photography group that had broken new ground as a “self-agency”, which some suggest was also inspired by the famous Magnum agency, founded a decade earlier, though under quite different conditions. Vivo was formed as a group of independent, creative, yet industry savvy professionals, so the independent work of its members crossed paths with many artists, writers, sculptors, performers and models of their time. More importantly perhaps, with work ranging from the documentary to the realms of commercial photography, their work and spirit quickly inspired others, and has continued to do so.

The first few photos didn’t seem to point in any particular direction, however: Ikko Narahara’s series, set in what looks like a Japanese Franciscan monastery…then a prison, or asylum. These images are characterised by interesting angles, punchy contrasted prints; they are grainy, but not to the extent of the 1960s bure boke Provoke photographers. For original circa 1960 prints, like the other works, they lacked nothing in terms of crispness or depth of tone.

Next, Akira Tanno’s photos of the circus, then some ballet and classical music stars. Very tight long-shots, they compromised a little on focus, but remain remarkable in that they predate the zoom-lenses that would make this framing more regular from the later Sixties onwards. Eikoh Hosoe’s well-known ‘Man and Woman’ abstract nudes (shown above right, and recently used to advertised his retrospective in Ebisu) and the famous Barakei (Ordeal by Roses) series of portraits of infamous writer Yukio Mishima are still engaging. Though familiar with the series, they were certainly worth seeing ‘up close and original’, and took on a richer meaning when seen alongside the other works.

Behind me, unfortunately ‘wrapped’ around a pillar near the entrance, Akira Sato’s series suggested something of Vivo’s professionalism and commercial intentions. Although they are dramatic, ‘clever’ portraits, they could look a little dated now, like good advertising photography. Some would say that photography, as a medium, exists precisely in this blurred relationship: sometimes a ‘fine craft’, yet often responding to industry led innovation.

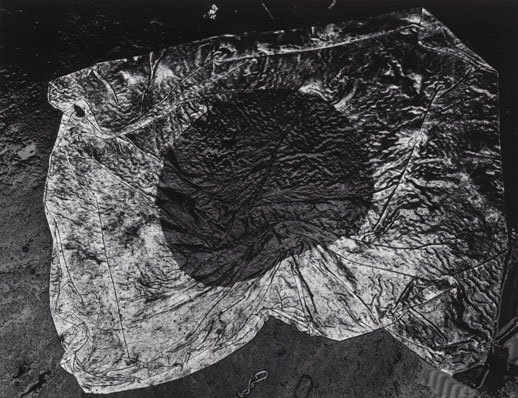

The work of Kikuji Kawada and Shomei Tomatsu, however, signalled a thematic and aesthetic shift. Moving between nostalgia, remorse, anger and introspection, both deal with the physical results of the atomic bombs: ruins, victims, artefacts, memories, proof… Some of the photographs were literally ‘constructed’, it seems, with a particular emotional imperative. Considering that these are ‘documentary’ style images, of an ordeal that took place 15 years earlier, suggested something of the tense uncertainty of ‘freedom’ in Japan as it headed in to the 1960s. Perhaps one shouldn’t look at these images as resolved or decided. Tomatsu later wrote:

“A photographer is both a passer-by and a dweller. (…) [they] cannot cure like a doctor, cannot defend like a lawyer, cannot analyze like a scholar, cannot support like a priest, cannot bring about laughter like a rakugoka, cannot entertain like a singer, but can merely look. That’s good enough. Well, no, that’s all there is.”1

It is interesting to consider Vivo as a group (of photographers, and photographs) that younger photographers such as Daido Moriyama, Nobuyoshi Araki and so on were seeing, and being influenced by; Vivo may have worked as a model to work from, and against. Vivo’s aesthetics, as well as the now ‘simple’ idea of an individual approach certainly explain its treatment as a forerunner of subsequent important developments in Japanese photography. But only looking at this work in terms of its connection to history overlooks the work’s significance and intentions in its own time.

So, as a piece in what is often the puzzle of post-war Japanese photography, Vivo certainly connects to many of the other important pieces that followed: experiments, groups and photo-books. Actually, Moriyama came to Tokyo intent on joining Vivo, but it disbanded. He then somehow became Eikoh Hosoe’s assistant, beginning with the Barakei series… there are thus more pieces which remain – at least to me – further questions to be keenly explored.

___

1 Shomei Tomatsu, “The Man Who Said: ‘I saw it! I Saw It!’ and Passed it By”, originally published in Taiyo No Enpitsu, Tokyo Mainichi Shinbun, 1975. This translation taken from Ivan Vartanian, Setting Sun : Writings by Japanese Photographers, Aperture Foundation, 2006; pp.28-29.

Olivier Krischer

Olivier Krischer